Prospective Greg Craig Jurors Are Pressed About Any Mueller Bias

There were lawyers, consultants, at least one teacher, an anthropologist and a political consultant, all facing the possibility of serving on the jury that will weigh the government's evidence against the former Skadden partner and ex-Obama White House counsel.

August 14, 2019 at 07:57 PM

6 minute read

Gregory Craig. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/NLJ

Gregory Craig. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/NLJ

When the bespectacled man in a light blue t-shirt walked into court Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson of the District of Columbia first wanted to know what he’d heard about the Greg Craig case.

That morning, with statues of Moses and Hammurabi above him and more than 100 other prospective jurors gathered in the E. Barrett Prettyman Courthouse’s ceremonial courtroom, the man had written the number “5” in pencil on a blue notecard, signifying he had some familiarity with the case. In the witness chair a couple hours later, in Jackson’s courtroom, he was asked to elaborate.

He said he’d followed the Russia investigation “with some interest” and recalled being surprised to read that someone who’d worked for President Barack Obama was “implicated in the matter.” Then he read that the case against Obama’s first White House counsel involved the Foreign Agents Registration Act, an 80-year-old law requiring the disclosure of foreign influence campaigns in the United States.

“When I saw it was a FARA thing, it didn’t really interest me,” said the potential juror, who works in the health and human services industry.

By day’s end, he was among 35 potential jurors who’d been deemed qualified for Craig’s trial.

Wednesday’s winnowing of prospective jurors set the stage for prosecutors and Craig’s defense to further examine the pool Thursday, as the two sides prepare to make their case to a panel of 12. Opening statements are expected to follow.

On Wednesday, there were lawyers, consultants, at least one teacher, an anthropologist and a political consultant, all facing the possibility of serving on the jury that will weigh the government’s evidence against Craig.

Craig was charged in April with deceiving the Justice Department about his work for Ukraine in 2012, when he was a partner at the law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. His case had been referred by the special counsel’s office to the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, but career prosecutors in Washington ultimately accused him of misleading the Justice Department to avoid registering as a foreign agent.

Several prospective jurors were asked not only about their thoughts on the special counsel’s investigation but also Paul Manafort, who helped arrange for the Russia-backed government of Ukraine to hire Skadden. Manafort, a longtime Republican political consultant and former chairman of the Trump campaign, was convicted last year on financial fraud charges linked to his past work for Ukraine, in the first trial win for the special counsel’s team.

Facing questions about Manafort on Wednesday, the prospective juror in the health services industry said, “I hold his work in contempt, that’s all.”

In Wednesday’s pool of potential jurors, the backgrounds varied widely, but many shared a common trait: news junkie.

A lawyer described a vigorous news diet that included newspapers and occasional cable news viewing. “I grew up in a household that got hard copy papers,” the lawyer said. “So I’m fairly plugged in.”

One woman who passed into the pool of 35 would-be jurors described herself as an avid viewer of MSNBC. When asked whether he could refrain from tuning in if ultimately seated on Craig’s jury, she replied, “It would be hard, but I would not watch.”

Robert Mueller, former special counsel for the U.S. Department of Justice, testifies before the House Judiciary Committee in Washington, D.C., U.S., on July 24.

Robert Mueller, former special counsel for the U.S. Department of Justice, testifies before the House Judiciary Committee in Washington, D.C., U.S., on July 24.Another woman, who said she was in the “cyber field,” claimed to have read from “cover to cover” the 448-page report Robert Mueller’s office prepared on its two-year investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. “I have a high regard for Robert Mueller and the integrity of that office,” the woman said.

For Jackson, the response raised the question: Would she favor the prosecution if she knew Craig’s case arose out of Mueller’s investigation?

“Yes,” the prospective juror said.

Would you be able to set aside your view of the special counsel’s office?

“No,” the juror said. “I don’t think so.”

The prospective juror was asked to leave the courtroom, and she was excused from the jury pool.

U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM

U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson. Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALMWednesday’s court action was a redo of a process that began Monday but was promptly scrapped. Between the end of Monday’s proceeding and Tuesday morning, the Justice Department raised concerns about whether the closed-door approach to juror selection infringed on Craig’s constitutional right to receive a fair trial.

Craig’s defense team formally objected Tuesday to the jury selection process, and so the second day of Craig’s trial ended with the judge agreeing to start the jury selection process from scratch.

At the end of Wednesday’s proceedings, Jackson remarked that the trial was now in the same place it was two days earlier.

“It feels like five years ago,” Jackson said, “but it was only Monday.”

Read more:

‘Are You Telling Me We Need to Start Over?’ How Greg Craig’s Trial Hit a Snag

Quinn’s William Burck Is Now a Registered ‘Foreign Agent’ for Kuwaiti Contractor

Registering as a ‘Foreign Agent’? Why Law Firms and Lobby Shops Might Demur.

Manafort Judge Says Foreign Lobbying Law Is No ‘Pesky Regulation’

The Curious Case of Joe Lieberman’s Work as a Lobbyist Who Isn’t ‘Advocating’

Greg Craig, Defiant After Lobbying Charges, Will Plead Not Guilty

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

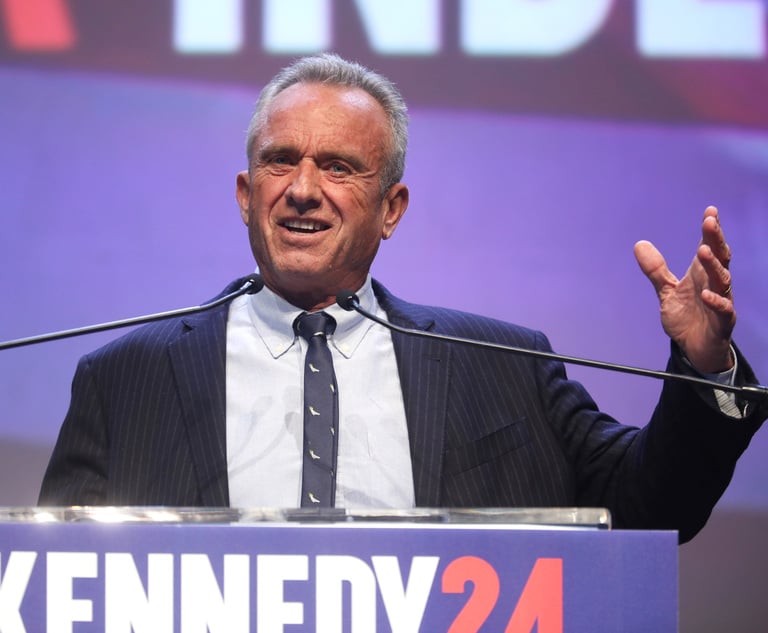

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

3rd Circuit Nominee Mangi Sees 'No Pathway to Confirmation,' Derides 'Organized Smear Campaign'

4 minute read

Judge Grants Special Counsel's Motion, Dismisses Criminal Case Against Trump Without Prejudice

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250