After Speedy Subpoena Cases, Trump Tax Disputes Linger

U.S. District Judges Trevor McFadden and Carl Nichols appear to be taking a deliberative approach in their handling of fights over the president's tax returns.

September 05, 2019 at 05:54 PM

7 minute read

D.C. District Judges Trevor McFadden (left) and Carl Nichols.

D.C. District Judges Trevor McFadden (left) and Carl Nichols.

A pair of federal judges in Washington, D.C., seem to be in no rush to decide whether House Democrats can get their hands on President Donald Trump's tax returns.

U.S. District Judge Trevor McFadden, who has shown himself to be methodical when it comes to legal cases involving the president, last week rejected House Democrats' request to fast-track their lawsuit seeking Trump's federal tax returns from the Treasury Department.

And U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols will have overseen a lawsuit surrounding Trump's New York tax returns for several weeks by the time he reaches a decision about where the case should even be held. New York state Attorney General Letitia James is trying to get the case dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

Those slow timelines by both judges, who are Trump appointees, are a marked difference from the speedy resolutions reached in district court over lawsuits challenging congressional subpoenas for the president's records from private financial institutions.

Federal trial judges in D.C. and the Southern District of New York—both appointees of President Barack Obama—issued rulings in the cases over congressional subpoenas issued to Mazars, Capital One and Deutsche Bank within weeks of the complaints being filed. Circuit courts are now poised to issue their rulings in those cases in the near future.

Legal experts say that the disparate timelines may be the result of varying styles among the different judges presiding over the cases. The federal tax return case before McFadden also involves records possessed by the federal government, rather than private parties, as in the subpoena cases, meaning he will have to tackle different questions about separation of powers.

"Unless there's some extraordinary reason for it to move faster, it's going to be a matter of months," Michael Stern, former senior counsel to the House from 1996 until 2004, said of McFadden's case.

Doug Letter.

Doug Letter.The Democratic-controlled House Ways and Means Committee asked McFadden to speed up their case earlier this month. House lawyers, including general counsel Douglas Letter, argued that they have a limited amount of time to get the tax returns and then draft legislation in response before their terms in Congress expire.

But McFadden didn't buy the argument. In an order last week, he rejected the request to expedite, questioning why the House attorneys waited seven weeks after filing the complaint to ask for an expedited briefing schedule.

And he pointed to decisions due to emerge from circuit court panels on other congressional subpoenas to Mazars, as well as Capital One and Deutsche Bank, as having the potential to guide his decision-making in the tax returns case.

"To be sure, this is no ordinary case, but the weighty constitutional issues and political ramifications it presents militate in favor of caution and deliberation, not haste," McFadden wrote. "And the Committee has not shown otherwise."

This is not the first time McFadden has shown himself to act methodically in a high-profile case. Earlier this year, the judge was wary of House Democrats' argument that they could sue the Trump administration over the diversion of military funds to construct a wall along the southern border with Mexico.

He ultimately ruled the House could not sue the executive branch. The case is currently being appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

Stern said that, because Trump sued in his private capacity to block the congressional subpoenas in the other cases, judges didn't have to consider whether the committees even had the ability to sue.

But the lawsuit over the federal returns was the first legal challenge proactively filed by House Democrats to get records held by the Trump administration, meaning that Main Justice lawyers can raise standing issues.

"Courts are reluctant to insert themselves in a dispute between the executive and legislative branches," Stern said. "So when Congress asks them to help, they have a lot of concerns about that, and they want to try, if possible, to avoid becoming the arbiters of the dispute."

Legal experts have said that House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard Neal, D-Massachusetts, is well within his rights to request Trump's tax returns under a 1924 law that states the Internal Revenue Service "shall" furnish lawmakers with requested tax records.

Neal initially requested the returns from the IRS under the law, but Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin said the committee lacked a legitimate legislative purpose for the documents. Mnuchin offered up the same reasoning when he later rejected a congressional subpoena for the returns.

Ilya Somin, a law professor at George Mason University, said judges are generally given broad discretion when it comes to setting the timelines for resolving their cases.

He said that, in the case surrounding Trump's federal returns, there might not be as much urgency as there is in other matters, like getting former White House counsel Don McGahn to testify before Congress as House Democrats weigh possible impeachment proceedings.

"If, ultimately, Trump's tax returns are made public, it will still have a political and legal impact if it happens three months from now or six months from now," Simon said.

There is the potential for lawmakers to get their hands on the documents through other means, particularly if they prevail in their battle to subpoena financial records from Deutsche Bank. The bank told a panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in a publicly redacted letter that it had tax returns of at least one Trump family member in its possession.

That panel heard oral arguments over the Deutsche Bank subpoena in late August, and a decision is expected in the coming weeks.

Several lawsuits also have been filed in the U.S District Court for the Eastern District of California challenging a California law that would require Trump to provide his tax returns in order to appear on the state's ballot. Judge Morrison C. England Jr. will hold a Sept. 19 hearing on the several motions for a preliminary injunction in those related cases.

Experts also said the pace of a case can depend on the judge overseeing the matter.

Charles Tiefer, a professor at the University of Baltimore's School of Law, said he believes McFadden "unfortunately, sees the case the way that the Trump side sees it."

"The tax case comes down to one word in the statute, namely that the IRS 'shall' provide the returns to the Ways and Means Committee," Tiefer said. "He's needlessly dragging out his reading of that one word."

Read more:

SDNY Judge, Too, Finds Congress May Subpoena Banks in Probe of Trump's Finances

US Judge Backs House Subpoena for Trump Financial Records

Who Is Trevor McFadden? Meet the Judge Assigned the Trump Tax Returns Case

Trump's Lawyers Drag Justices Into DC Circuit Subpoena Fight

Judge: House Lacks Standing to Sue Trump Administration Over Border Wall Funding

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Government Attorneys Face Reassignment, Rescinded Job Offers in First Days of Trump Administration

4 minute read

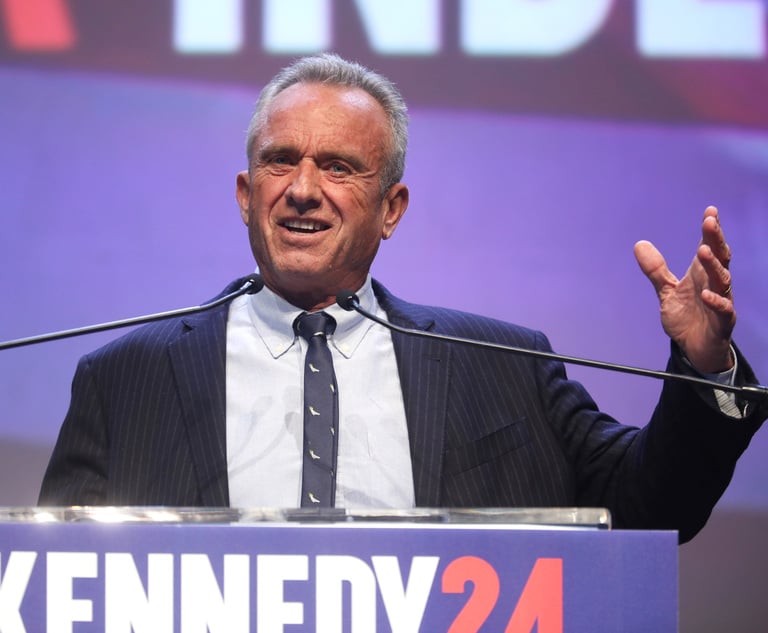

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Am Law 200 Firms Announce Wave of D.C. Hires in White-Collar, Antitrust, Litigation Practices

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Starbucks Sues Ex-Executive to Recover $1M Signing Bonus

- 2Navigating AI Risks: Best Practices for Compliance and Security

- 320 New Judges? Connecticut Could Get Wave of Jurists

- 4Orrick Loses 10-Lawyer Team to Herbert Smith in Germany

- 5‘The US Market Is Critical’: KPMG’s Former Head of Global Legal Services On the Legal Arm of the Big Four Firm Entering the US

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250