Roberts, Like Rehnquist Before Him, Would Preside Over a Trump Impeachment Trial

Rehnquist's 1992 book "Grand Inquests" chronicled the impeachment of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase in 1805 and President Andrew Johnson in 1868.

September 25, 2019 at 06:36 PM

6 minute read

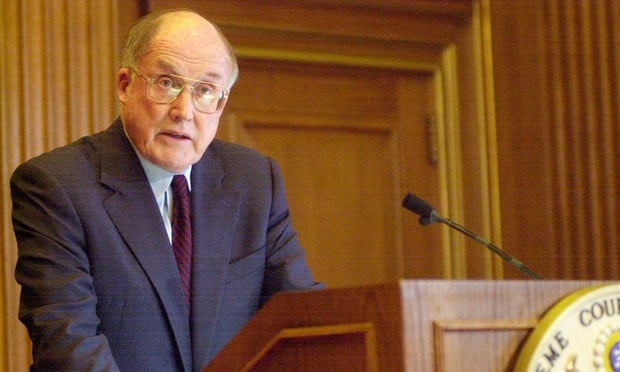

The late Chief Justice William Rehnquist. File photo.

The late Chief Justice William Rehnquist. File photo.

Seven years after he wrote a book about impeachment, then-U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist presided over one: the trial of President Bill Clinton in 1999, which resulted in acquittal. The book, and the experience, made Rehnquist an unparalleled expert on impeachment.

As the U.S. House moves forward with its impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump, one of Rehnquist's former clerks, now-Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., would be poised to preside over any trial in the U.S. Senate. Of course, only if the process gets to that point.

Roberts and Trump have a complicated history laced with rebukes from both sides.

Roberts portrays himself as an institutionalist, protective more of how the court—and the judiciary—is viewed than how he is seen. Last year, Roberts issued a rare rebuke of Trump after one of his criticisms of a court ruling by an "Obama judge." The chief said: "We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them."

The chief justice has long painted himself as a nonpartisan leader of the court, eschewing any notion that the justices take sides based on which president appointed them to the high court.

"When you live in a polarized political environment, people tend to see everything in those terms," Robert said in remarks Tuesday in New York. "That's not how we at the court function and the results in our cases do not suggest otherwise."

Trump has called Roberts a "nightmare" for conservatives and an "absolute disaster," criticism tied to the chief justice's rulings that upheld the signature Obama legislation the Affordable Care Act. Trump has said he would ask the Supreme Court to intervene if the House moved to impeach him. But that's not how it works—there is no appeal.

Rehnquist's 1992 book "Grand Inquests" chronicled the impeachment of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase in 1805 and President Andrew Johnson in 1868. Both ended in acquittals after failing to garner a two-thirds majority in the Senate as required by the Constitution.

The outcomes, in Rehnquist's view, established the important principle that impeachment must not be used lightly by Congress as a weapon to punish the other branches for policy differences.

"In retrospect, one cannot imagine anyone better qualified than Chief Justice Rehnquist to preside over the Clinton impeachment trial," Michael Gerhardt, a professor at University of North Carolina School of Law who's also written about impeachment, told The National Law Journal in a 2017 interview.

Rehnquist, who was an official in the Nixon Justice Department before joining the Supreme Court, was scrupulously nonpartisan and low key in running the Clinton trial. After it was over, Rehnquist borrowed a line from Gilbert and Sullivan in describing his role: "I did nothing in particular, and I did it very well." In February 1999, Clinton was acquitted in the U.S. Senate.

Rehnquist died in 2005 and his papers reside at the Hoover Institution in California. His impeachment files are closed to the public for the lifetime of other justices who served on the court with him.

Rehnquist's observations about impeachment in the book and other sources resonate in the current debate, Gerhardt said in the 2017 interview. "The lesson to be learned from Rehnquist that can be applied to Trump is to remember impeachment is not supposed to be a partisan tool. It is a last resort to be used for serious abuses of power or breaches of trust."

Some excerpts from Rehnquist's writings on impeachment:

Congressional supremacy: "Had these two trials resulted in conviction rather than acquittal, the nation would have moved closer to a regime of the sort of congressional supremacy that was dreaded by men such as James Madison, the Father of the Constitution. … We twice escaped from a precedent that would indeed have given us a Presidency, and a Court, subject to 'tenure during the pleasure of the Senate.'"

Indictable offense: "All members of the Judiciary Committee [investigating Richard Nixon] appear to have rejected the view that a constitutional 'high crime or misdemeanor' must be an indictable offense under the criminal law."

Overreaching and bullying: "One need only note the way in which the framers arranged the test of the United States Constitution to realize that they were concerned about the separation of powers within the new federal government they were creating. … The framers were particularly concerned about the possibility of overreaching and bullying by the legislative branch—Congress—against the other branches."

Answerable to the country: "The importance of the acquittal [of President Andrew Johnson] can hardly be overstated. With respect to the Chief Executive, it has meant that as to the policies he sought to pursue, he would be answerable only to the country as a whole in the quadrennial Presidential elections, and not to Congress through the process of impeachment."

Obstruction of justice: "The counts relating to the obstruction of justice and to the unlawful use of executive power [by President Nixon] were of the kind that would surely have justified removal from office."

Read more:

'Do Us a Favor': Trump Wanted Barr, Giuliani to Help Ukraine Investigate Biden

Roberts, Ruling Against Trump, Faces New Round of Conservatives' Criticism

Why Roberts Sided With Liberals Blocking Restrictive Louisiana Abortion Law

Chief Justice Roberts Joins Liberal Wing to Snub Alabama Court in Death Case

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'You Became a Corrupt Politician': Judge Gives Prison Time to Former Sen. Robert Menendez for Corruption Conviction

5 minute read

Sidley Adds Ex-DOJ Criminal Division Deputy Leader, Paul Hastings Adds REIT Partner, in Latest DC Hiring

3 minute read

‘High Demand’: Former Trump Admin Lawyers Leverage Connections for Big Law Work, Jobs

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1AIAs: A Look At the Future of AI-Related Contracts

- 2Litigators of the Week: A $630M Antitrust Settlement for Automotive Software Vendors—$140M More Than Alleged Overcharges

- 3Litigator of the Week Runners-Up and Shout-Outs

- 4Linklaters Hires Four Partners From Patterson Belknap

- 5Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250