Supreme Court Error Has a Long Shelf Life

Justice George Sutherland entirely misread Chief Justice John Marshall's sole-organ speech in a 1936 Supreme Court decision, leaving room for various levels of the executive branch to cite Sutherland's erroneous dicta to expand presidential power in foreign affairs over time.

October 21, 2019 at 04:42 PM

6 minute read

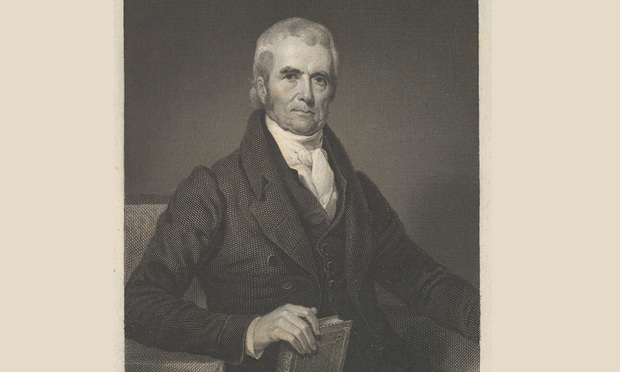

Chief Justice John Marshall (1833), painted by Henry Inman and engraved by Asher Brown Durand.

Chief Justice John Marshall (1833), painted by Henry Inman and engraved by Asher Brown Durand.

In an op-ed in the New York Times on Sept. 25, John Yoo cited a number of reasons to support broad powers for the president in external affairs. In part, he said that "under the Constitution and long practice, the president alone conducts foreign relations. As Justice George Sutherland wrote for the majority in a 1936 Supreme Court opinion (quoting Chief Justice John Marshall), the president 'is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations.'"

Marshall made that statement, but not as chief justice. It was as a member of the House of Representatives in 1800, when Jeffersonians had taken steps to either impeach or censure President John Adams for turning over to England an individual charged with murder. Critics of Adams thought the individual was a citizen of the United States, but research demonstrated he was Thomas Nash, a native Irishman.

In the course of a lengthy speech, Marshall added this sentence: "The president is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations." The phrase "sole organ" is ambiguous. "Sole" means exclusive but what is "organ"? Simply the president's duty to communicate to other nations U.S. policy after it has been decided by the elected branches? Anyone reading the entire speech would understand that Marshall was not advocating exclusive power for the president in external affairs. Such an interpretation would violate the plain text of Articles I and II of the Constitution.

Marshall explained that the Jay Treaty with England contained an extradition provision in Article 27 that directed each country to deliver up to each other "all persons" charged with murder or forgery. Nash therefore was being turned over to England for trial. Adams did not claim he had power to make foreign policy unilaterally. He was not the "sole organ" to formulate a treaty. He was the sole organ to implement it. After Marshall completed his speech, the Jeffersonians found his argument so tightly reasoned that they dropped efforts to impeach or censure Adams.

What was clear in 1800 became an error with litigation in the 1936 Supreme Court decision in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. At stake was legislation passed by Congress two years earlier, authorizing the president to impose an arms embargo in a region in South America whenever it could reestablish peace between belligerents. The issue was legislative, not executive, power. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt imposed the embargo, he relied exclusively on statutory authority.

The issue in Curtiss-Wright was whether Congress could delegate this particular power to the president. A district court held that the statute impermissibly delegated legislative authority. The case moved directly to the Supreme Court. None of the briefs discussed the availability of plenary or exclusive power for the president is external affairs. Sutherland reversed the district court and upheld the delegation. However, he proceeded to add material entirely extraneous to the issue before the court ("dicta"). Not merely dicta but erroneous dicta.

For example, Sutherland claimed that the Constitution commits treaty negotiation exclusively to the president. Nothing in the case had anything to do with treaties or treaty negotiation. If one wants a persuasive source to repudiate the notion of presidents empowered to negotiate treaties by themselves it would be a book published in 1919, Constitutional Power and World Affairs. It reflects the views of someone who served in the U.S. Senate for 12 years and understood the frequency with which his colleagues participated in treaty negotiation. Who wrote the book? Sutherland.

In Curtiss-Wright, Sutherland proceeded to entirely misread Marshall's sole-organ speech. Instead of acknowledging that Adams was merely carrying out a treaty, Sutherland insisted that the president possessed "plenary and exclusive" power over external affairs. Although nothing in Marshall's speech remotely makes that claim, various levels of the executive branch, assisted at times by constitutional scholars, began to cite Sutherland's erroneous dicta to expand presidential power in foreign affairs. In his 1941 book The Struggle for Judicial Supremacy: A Study of a Crisis in American Power Politics, Robert Jackson described the dicta in Curtiss-Wright as "a Christmas present to the President." Executive branch attorneys cited the decision with great frequency. As explained by Harold Koh in The National Security Constitution, Sutherland's "lavish description" of presidential power is so often quoted that "it has come to be known as the 'Curtiss-Wright, so I'm right' cite."

Legislation during the George W. Bush administration led to litigation that invited a new look at Curtiss-Wright dicta. In signing a bill in 2002 dealing with the issuance of passports to U.S. citizens born in Jerusalem, Bush objected to some provisions he regarded as interfering with the constitutional functions of the president in foreign affairs. By referring to the president's constitutional authority to "speak for the nation in international affairs," he implicitly, if not explicitly, relied on the sole-organ doctrine.

Litigation continued at various levels. At one point, on July 23, 2013, the D.C. Circuit upheld independent presidential power in external affairs by relying five times on the sole-organ model. In response, I filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court on July 17, 2014, explaining the erroneous dicta in Curtiss-Wright and urging the court to correct them. On Nov. 3, 2014, the National Law Journal selected my brief as "Brief of the Week," selecting this provocative title: "Can the Supreme Court Correct Erroneous Dicta?"

On June 8, 2015, in Zivotofsky v. Kerry, the Supreme Court finally rejected the sole-organ doctrine but never explained how Sutherland flagrantly misrepresented Marshall's speech. Moreover, the court created a substitute model of independent presidential power in external affairs, attributing to the president such abstract qualities as unity, decision, activity, secrecy and dispatch. There is no reason to assume that those five qualities are inherently positive for making and executing national policy or consistent with the Constitution.

Louis Fisher is visiting scholar at the William and Mary Law School. His most recent book is "Reconsidering Judicial Finality: Why the Supreme Court is Not the Last Word on the Constitution." One of the chapters is devoted to the sole-organ doctrine.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Restoring Antitrust: Returning to the Consumer Welfare Standard

New York Mayor Adams Attacks Fed Prosecutor's Independence, Appeals to Trump

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250