How a Legacy Scalia Clean-Water Ruling Played into Hawaii Case at SCOTUS

In "County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund," lawyers for each side, including the United States as amicus, find support in Scalia's plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States.

November 06, 2019 at 03:13 PM

5 minute read

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM)

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM)

A "quagmire" of a Clean Water Act ruling that Justice Antonin Scalia wrote more than 13 years ago could now play a central role in the outcome of the U.S. Supreme Court's most important environmental case this term.

In County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, lawyers for each side, including the United States as amicus, find support in Scalia's plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States. At issue is whether the federal clean water law requires certain permits when pollutants are conveyed from one source via groundwaters to navigable waters.

In the background, an internal fight has raged between Maui's mayor, the county council and the corporation counsel over whether there's even a live dispute for the justices to resolve. Although the Supreme Court was informed of a possible settlement, no questions were asked about it during arguments Wednesday.

Under the Clean Water Act, the definition of the term "discharge of a pollutant" includes "any addition of any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source." The case involves the discharge of pollutants from injection treatment wells in Maui.

During Wednesday's arguments, Elbert Lin, partner at Hunton Andrews Kurth, argued Maui is not violating the act's permit requirements when pollutants from its wells reach navigable waters via groundwaters. The act, he said, is concerned only with "point source" pollution—an identifiable source of the pollution—and groundwater is a conveyance, not a "point source" of the pollution.

Rapanos was a fractured 4-1-4 decision in which Scalia adopted a hydrographic test to define the Clean Water Act's jurisdiction over waters. The relevant part of his opinion for the Maui case is that the act "does not forbid the 'addition of any pollutant directly to navigable waters from any point source,' but rather the 'addition of any pollutant to navigable waters.'"

Lin's argument " sounds like the 'directly' [to navigable waters] argument that Justice Scalia's opinion rejected," Justice Brett Kavanaugh told him.

"Yes, your honor, the Rapanos plurality that Justice Scalia wrote, we think it's factually consistent with our reading," Lin said, responding to Kavanaugh. "We think he was concerned about point source-to-point source pollution."

But David Henkin, counsel to the wildlife fund, countered that the Clean Water Act does not limit permits only to point source-to-point source pollution.

"The Clean Water Act prohibits unpermitted additions of pollutants to navigable waters from any point source," Henkin said. "This prohibition is not limited to pollutants that flow directly from a point source to navigable waters. The word 'directly' is nowhere in the text. For three decades, EPA interpreted the Clean Water Act prohibition this way."

A major concern raised by several justices during Wednesday's arguments was whether there is some "limiting principle" for whichever way they rule on the ground water question. For example, if Henkin wins, what would protect a homeowner with a leaking septic tank from the hassle and expense of a permit and fines of $50,000 per day for violations? And if Lin prevails, how is a polluter stopped from evading permits by using groundwater as a conveyance?

Lin said the federal law requires states to have nonpoint source management programs and that there are grants and incentives in place for states to regulate. States also, as a "water quality backstop," are required every two years to identify waters failing to meet water quality standards.

But Justice Elena Kagan responded, "The question is not whether there's a possible state backstop. The question is what Congress was doing in this statute." The pollution here, she added, is from a point source, which is the well, and it's to navigable waters, which is the ocean, and it's an addition. How does this statute not apply?"

And Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. was skeptical of Henkin's limiting principle: The pollution must be fairly traceable to the point source and that source be the proximate cause. Fairly traceable, he said, depends on the sophistication of instruments identifying and tracing the pollution and proximate cause is "notoriously manipulable."

The United States supported the plaintiffs in the lawsuit in the lower courts, but in April the government changed its position. An amicus brief by a bipartisan trio of former EPA administrators, represented by former assistant to the solicitor general Sarah Harrington, partner at Goldstein & Russell, urged the justices to reject the solicitor general's "newly discovered and misguided interpretation" of the Clean Water Act.

Besides the United States, the case has drawn numerous amicus briefs from business, industry, environmental , former EPA officials, legal organizations, and others, represented by such major law firms as Mayer Brown, Kirkland & Ellis, Beveridge & Diamond, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, Hogan Lovells, Crowell & Moring, and Robbins, Russell, Englert, Orseck, Untereiner & Sauber.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Government Attorneys Face Reassignment, Rescinded Job Offers in First Days of Trump Administration

4 minute read

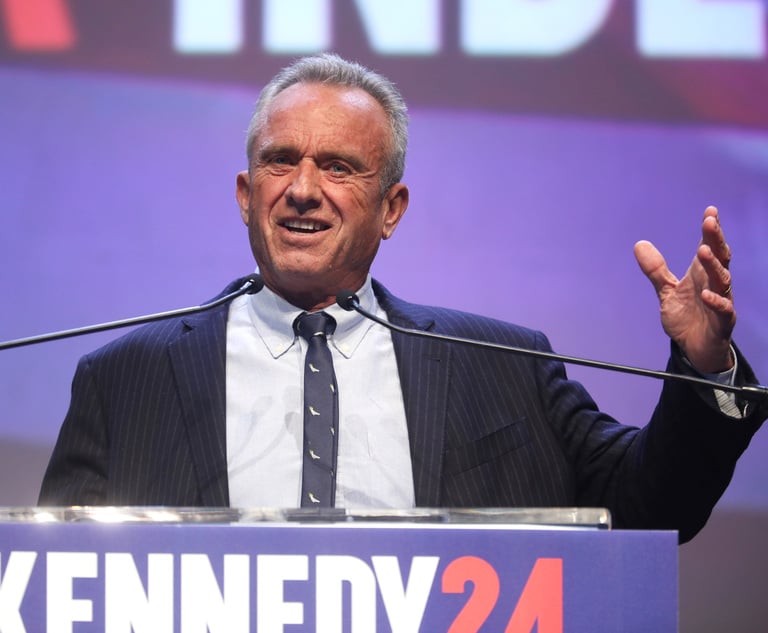

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Am Law 200 Firms Announce Wave of D.C. Hires in White-Collar, Antitrust, Litigation Practices

3 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250