SCOTUS Passes on Reviewing Patent Eligibility

Bucking the solicitor general's and Federal Circuit's urging, the U.S. Supreme Court won't take medical diagnostics case—or two other Section 101 cases where it had sought the SG's views, which means Congress is now more likely to get involved.

January 13, 2020 at 12:58 PM

7 minute read

Jonathan Singer of Fish & Richardson, counsel of record to Mayo Collaborative Services.

Jonathan Singer of Fish & Richardson, counsel of record to Mayo Collaborative Services.

After dipping a toe back in the patent eligibility waters, the U.S. Supreme Court has decided against diving all the way back in.

The justices denied certiorari Monday in two cases in which the court had sought the views of the solicitor general, HP v. Berkheimer and Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA v. Vanda Pharmaceuticals. Either case could have forced the court to reconsider a quartet of Section 101 cases that have tilted the law of patent eligibility away from patent owners and more toward accused infringers.

Solicitor General Noel Francisco had recommended against taking each case but had strongly urged the court to reconsider its eligibility law generally, and to use Athena Diagnostics v. Mayo Collaborative Services as the vehicle. All 12 active members of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit had likewise called on the court to use Athena to clarify the law of eligibility as it applies to diagnostics. But the court rejected Athena as well.

The upshot is that no changes are now likely to the court's Section 101 case law for the foreseeable future, shifting the spotlight back to Congress, which held hearings on the issue last spring and summer.

"I think they are done with this," said Stanford University law professor and Durie Tangri co-founder Mark Lemley. "It's hard to imagine a better case than one where all 12 Federal Circuit judges and the DOJ urge them to take it."

"I do think this will spark renewed movement in Congress," Lemley added. "But it also means the Federal Circuit has very little constraint on what it can do, even when it effectively underrules a Supreme Court decision (as they did in Hikma v Vanda). So we may see more en banc activity and more inconsistent panel decisions in the meantime."

The court could also be waiting on further development of the law before taking any more action, said Villanova University law professor Michael Risch said.

"As more patents are filed post-Alice, we may see a reshaping of patent claiming that eliminates the need for further case," Risch said.

Meanwhile, in other Supreme Court patent news, the court also denied certiorari in Regents of the University of Minnesota v. LSI, in which more than a dozen states and hundreds of universities were demanding the restoration of their sovereign immunity from administrative patent validity challenges at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The universities had argued the America Invents Act trials that are conducted before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board are similar enough to civil litigation that their immunity should apply. The Federal Circuit had disagreed.

As for eligibility, the Supreme Court overhauled it beginning with Bilski v. Kappos in 2010 and ending with Alice v. CLS Bank in 2014. The high court clarified its view that abstract ideas, laws of nature and natural phenomena are not eligible for patenting.

The U.S. Senate Judiciary's IP Subcommittee convened a series of hearings on the subject last year and released a draft framework of legislation that would overrule the Supreme Court's decisions. But the framework was met with criticism, and no formal legislation has yet been introduced.

The USPTO issued new guidance on Section 101 for patent examiners that emphasized that abstract ideas or natural phenomena that are integrated into a practical application can pass muster. But the USPTO guidelines are not binding on courts.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which has the last word on patent law short of the Supreme Court, has struggled to apply the high court's precedents on a consistent basis, with one judge accusing his colleagues last year of waging "guerrilla warfare" against the Alice decision.

Nowhere was the appellate court's frustration more evident than in Athena Diagnostics. In a 7-5 vote denying en banc review, all 12 active members of the court called on the Supreme Court or Congress to revisit patent eligibility as it's applied to medical diagnostics.

Athena's counsel of record, Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr partner Seth Waxman, called it "an unprecedented cry for help" in his petition for certiorari. "This Court should heed that cry and provide much-needed guidance on the proper application of the judicially-created exceptions to Section 101 of the Patent Act," he wrote.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the Biotechnology Innovation Association and the Intellectual Property Owners Association were among the amici curiae supporting certiorari.

Mayo was represented by Fish & Richardson, which argued that the court correctly decided this issue just seven years ago in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Labs, the second in the Supreme Court's quartet of decisions. It endorsed "a bright-line prohibition" against patenting laws of nature, argued Fish partner Jonathan Singer, who was counsel of record to Mayo.

At issue in Athena was U.S. Patent 7,267,820 held by Oxford University and the Max Planck Society and licensed to Quest Diagnostics Inc. subsidiary Athena Diagnostics Inc. The inventors discovered that antibodies to a protein called muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) are correlated with neurological disorders such as myasthenia gravis. The Mayo Clinic developed a competing test that Athena accuses of infringing.

The court had asked for the solicitor general's views on Hikma and Berkheimer. The SG recommended against taking both but stressed that that it was time for the Supreme Court to revisit Section 101 in an appropriate case.

"As the government's brief dramatically illustrates, there is a raging debate over the scope and wisdom of this Court's unanimous decision just seven years ago in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc.," Hikma's attorneys at Winston & Strawn and Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati argued in a Dec. 20 response to the solicitor general's brief.

Hikma addresses the patentability of methods of treating disease, such as new dosing regimes for existing drugs. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled 2-1 that Vanda's patent on a method of treating schizophrenia, by determining a patient's particular genotype and adjusting dosage of iloperidone accordingly, is eligible for patenting. Vanda's successful opposition was led by counsel of record Nicholas Groombridge, who is a partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

HP v. Berkheimer involves a computer-implemented invention. The question is whether the second step in the Supreme Court's patent eligibility framework—determining whether a skilled artisan would have considered claimed processes routine and conventional at the time of the patent—is a question of law or fact. The Federal Circuit held the latter in 2018, making it more difficult for accused infringers to get patent suits dismissed early on the pleadings.

HP was represented by Morgan, Lewis & Bockius and Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. Morgan Lewis Washington partner David Salmons was counsel of record. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, Computer & Communications Industry Association, Engine Advocacy and finance-industry supported Askeladden were among those urging the court to grant cert.

Jenner & Block partner Adam Unikowsky led the successful opposition, with help from Much Shelist and Skiermont Derby.

Villanova's Risch said that, although the court took no cases, it may have, in a sense, been striking a compromise. By leaving in Berkheimer in place, patent owners gain some procedural protections. The court leaves the substantive law in place, perhaps because it continues to believe medical diagnostic tests should not be patent eligible, he said.

"This result makes sense to me in the end," said George Washington University law professor Dmitry Karshtedt. "If I'm on the Supreme Court and not steeped in the turmoil with 101, these three opinions are just examples of case-by-case development of the doctrine that was sent down in Mayo [v. Prometheus] and Alice.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Hogan Lovells, Jenner & Block Challenge Trump EOs Impacting Gender-Affirming Care

3 minute read

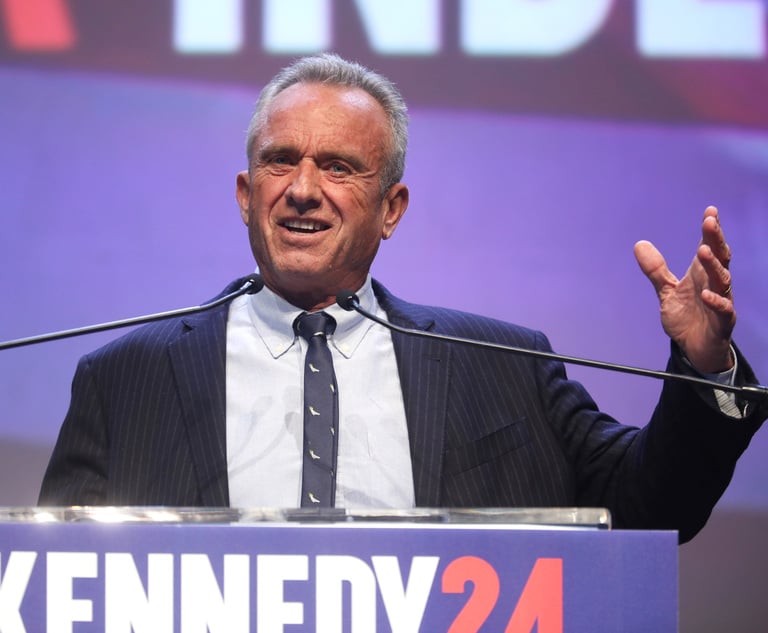

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

'Religious Discrimination'?: 4th Circuit Revives Challenge to Employer Vaccine Mandate

2 minute read

'Pull Back the Curtain': Ex-NFL Players Seek Discovery in Lawsuit Over League's Disability Plan

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 2Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 3Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 4Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

- 5'Intrusive' Parental Supervision Orders Are Illegal, NY Appeals Court Says

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250