DOJ Warns Search Warrant Ruling Could 'Seriously Disrupt' Investigations

The U.S. Justice Department is asking the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit to reconsider a ruling that questioned the government's use of a "filter team" to review files taken from a law firm as part of a criminal investigation.

January 16, 2020 at 02:21 PM

6 minute read

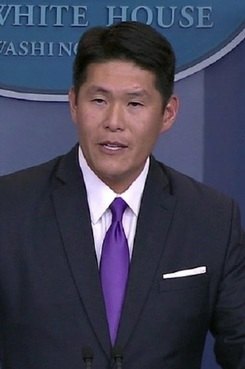

Maryland U.S. Attorney Robert Hur

Maryland U.S. Attorney Robert HurFederal prosecutors in Maryland are warning about the possibility of "seriously disrupted" criminal investigations following a U.S. appeals court ruling that questioned the integrity of allowing government agents to use their own internal teams, and not the courts, to review certain materials seized during the execution of search warrants.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit assailed Maryland prosecutors last year for using a so-called filter team to review documents and email files taken from the offices of a Baltimore law firm as part of an ongoing criminal investigation. The appeals panel said a federal magistrate judge, and not investigators themselves, should have conducted the inspection of the files to better protect any attorney-client relationships.

Filter teams are common across federal prosecution offices, and the one used in the Maryland investigation had been court-approved. The government sets up these teams in circumstances where the authorities want to wall-off primary investigators from being able to see information that could be protected. White-collar defenders, closely watching the Maryland litigation, said the Fourth Circuit's ruling carried a potential to "upend long-standing and well-established processes."

Government lawyers on Wednesday asked the Fourth Circuit to reconsider the three-judge panel decision, arguing that any broad movement by judges within the jurisdiction of the appeals court to embrace and implement the decision could impede investigations. The court hears federal appeals from Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina.

"The panel mistakenly adopted the analytical framework for resolving privilege disputes in civil litigation instead of the Fourth Amendment framework for ensuring that searches and seizures are conducted in a reasonable manner," Jason Medinger, chief of appeals for the Maryland U.S. attorney's office, told the appeals court. Medinger appeared on the brief with Maryland U.S. Attorney Robert Hur, a former King & Spalding white-collar partner. The government called filter teams "vital and reasonable under the Fourth Amendment."

Medinger argued that the panel decision's "sometimes-broad language has created a pall of uncertainty over well-accepted investigatory practices within this circuit." The ruling's "analytical errors threaten to seriously disrupt important criminal investigations across a range of important subjects throughout the entire circuit," he said.

James Ulwick of Baltimore's Kramon & Graham, who argued against the government in the Fourth Circuit case, said Thursday that the panel decision, written by Judge Robert King, "got it exactly right."

"Privilege determinations should be made by courts, not by the party adverse to the privilege," Ulwick said in an email. "As Judge King wrote for the unanimous panel, what the government seeks would allow the government's fox to guard the law firm's henhouse. If the 4th Circuit asks us to respond to this petition, we will do so, but nothing in this petition should cause the 4th Circuit to rethink its eminently correct and reasonable decision."

The Fourth Circuit, like many federal appeals courts, rarely grants petitions challenging a three-judge panel decision. The court said it grants "en banc" rehearing petitions—where the full court meets to consider a dispute—in less than 1% of the cases where such a sitting is requested.

Court papers do not reveal the name of the law firm that was hit with a search warrant, and the papers do not reveal the name of any lawyer or lawyers whose records prosecutors wanted to review. The Washington Post and Baltimore Sun have published reports identifying Kenneth Ravenall, a criminal defense attorney, as having been under investigation at the time the search warrant was served. Ravenall was indicted in September on conspiracy charges. He has pleaded not guilty.

Ravenall's lawyer, Lucius Outlaw, told the Post recently that the Fourth Circuit's ruling against the government marked a "stop to this grave threat to the attorney-client privilege, which is a fundamental pillar of our legal system, and no reason exists for overturning it."

The Fourth Circuit's ruling criticized not just prosecutors but also the Virginia-based federal magistrate who had approved the government's use of a filter team. The appeals panel said it was "troubled" that the magistrate "gave no indication that she had weighed any of the important legal principles that protect attorney-client relationships."

"Put simply, the filter protocol authorized government agents and prosecutors to rummage through Lawyer A's email files," King wrote. He was joined by Chief Judge Roger Gregory and Judge Allison Rushing, who joined the bench only a few months ago.

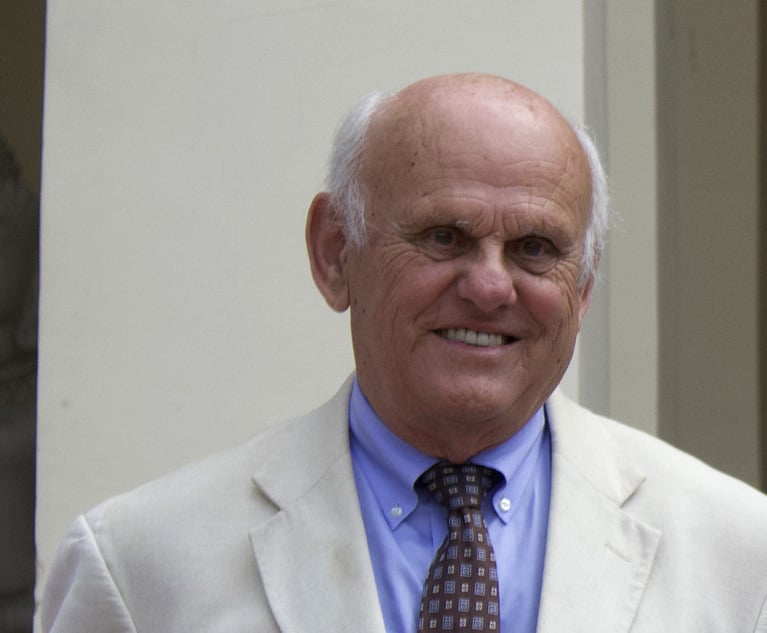

Former Manhattan federal judge and current Bracewell partner Barbara Jones/courtesy photo

Former Manhattan federal judge and current Bracewell partner Barbara Jones/courtesy photoThe court pointed to, and praised, the process that was crafted in New York in the dispute over searching files seized from Michael Cohen, the lawyer and one-time fixer for Donald Trump. In that case, a federal trial judge in Manhattan rejected the government's proposed filter team and instead appointed a special master, Barbara Jones, a retired federal judge, to review the Cohen files.

Maryland prosecutors said in Wednesday's court filing that the Cohen case presented "unusual circumstances" that justified using a third party to review seized files. The government also said it did not read the Fourth Circuit's ruling as flatly outlawing the use of filter teams.

"[T]he fact that special masters represent an option in some rare circumstances does not mean that they represent a reasonable balance of interests in all circumstances," Medinger wrote. He noted that the special master in the Cohen case "took more than four months to complete its review, at a cost of more than $960,000."

Federal magistrate judges, Medinger argued, "simply do not have sufficient time or staff to perform the sort of extensive document-by-document review that the panel required in this case."

"Imposing those sorts of costs and delays in every case would give short shrift to the public's substantial interest in expedient investigations," Medinger said.

Read more:

'None of the Government's Business': Prosecutors Rebuked Over Search of Law Firm

Williams & Connolly's Allison Rushing Is Confirmed to 4th Circuit Seat

Special Master Finishes Privilege Review of Cohen Material

Meet Chief Judge Roger Gregory, Fourth Circuit's Travel Ban Basher

Ex-King & Spalding Partner Robert Hur Follows Rosenstein as Maryland US Attorney

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Dissenter Blasts 4th Circuit Majority Decision Upholding Meta's Section 230 Defense

5 minute read

Justice 'Weaponization Working Group' Will Examine Officials Who Investigated Trump, US AG Bondi Says

Judge Pauses Deadline for Federal Workers to Accept Trump Resignation Offer

Judge Accuses Trump of Constitutional End Run, Blocks Citizenship Order

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250