Impeachment: What Trump's Missing Witnesses Say

We have a party, in a trial, who controls the witnesses who know his true conduct, and that party is using that control to block important witnesses from testifying. Our legal system saw this problem coming.

January 31, 2020 at 01:46 PM

5 minute read

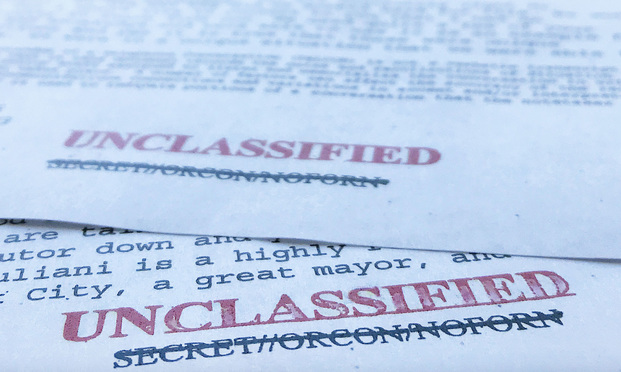

Transcript of a telephone conversation between U.S. President Donald Trump with Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelensky, held July 25, 2019.

Transcript of a telephone conversation between U.S. President Donald Trump with Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelensky, held July 25, 2019.

In the ongoing Senate impeachment trial, the White House's defense of President Donald Trump hinges on keeping damning documents and witness testimony out of evidence. That is why, for the first time in our history, a president has defied every request for documents and witnesses from House impeachment investigators, and gone to extraordinary lengths to stop members of his own administration from testifying.

We have a party, in a trial, who controls the witnesses who know his true conduct, and that party is using that control to block important witnesses from testifying.

Our legal system saw this problem coming.

The "missing witness" rule, a longstanding common-law rule that the U.S. Supreme Court first discussed in 1893 in Graves v. United States, allows one party to obtain an adverse inference against the other for failure to produce a witness under that party's control with material information—an inference that the testimony would be harmful to them. Similar principles allow an adverse inference when a party refuses to turn over relevant documents. These rules prevent obstinate parties from abusing "costly and time consuming" court proceedings to subvert their legal duty to produce relevant evidence, as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit noted in International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) v. National Labor Relations Board.

On Wednesday, I asked the House managers whether senators should draw an adverse inference regarding witnesses and documents withheld by the Trump administration. Witnesses like former national security adviser John Bolton, White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney, Assistant to the President Robert Blair, and top Office of Management and Budget (OMB) official Michael Duffey have direct knowledge of the president's efforts to block aid to Ukraine. Documents at the Department of State, OMB and the Department of Defense corroborate the stories of career civil servants, who defied Trump's blockade and testified before the House.

Sometimes it is proper to exclude relevant evidence from a trial. Evidence may be unduly prejudicial or subject to a valid assertion of privilege. Parties can then file motions to compel or motions in limine. They make their case document by document and witness by witness.

However, a litigant cannot unilaterally decide what evidence is presented—and that is just what the White House attempted, and what my Republican colleagues in the Senate are ready to allow. The White House's refusal to produce these materials to Congress is particularly wrongful because they are releasing subpoenaed documents—often heavily redacted—through Freedom of Information Act requests.

There is a well-established procedure for the assertion of executive privilege; the president has never exercised it. Had he, it would have required privilege logs and triggered a process of negotiation and accommodation to balance the institutional interest the president has in confidential communications against Congress' institutional interest in conducting oversight. But here we have a White House saying, no witness, no documents, no way, no how.

This takes us to the White House counsel's defense against drawing an adverse inference: the argument that they interposed meritorious, good-faith objections and privileges. This does not pass scrutiny in my view. We heard arguments about absolute immunity—arguments that have been rejected by every court that has ruled on the issue. We heard claims that a vote of the full House on impeachment was required for standing committees to authorize subpoenas—claims that have no basis in the Constitution or the House rules, and overlook House oversight powers. Trump's lawyers claim we lack the evidence to impeach the president, while the president has bragged, "We have all the material. They don't have the material." They have faulted the House for not enforcing subpoenas in court, while arguing in court that courts are powerless to enforce them. The White House blockade does not evidence good faith and merit.

An added indication of the White House's intent is their argument that calling witnesses will cause the Senate impeachment trial to grind to a halt while the parties go to court to litigate issues of privilege. That argument has no basis. The Constitution mentions no such review, and the Supreme Court has held that courts have "no role" in a Senate impeachment, in Nixon v. United States. The Senate, with the assistance of the presiding officer, has always decided questions of privilege in impeachments, without parties resorting to the federal courts. There is no support for this assertion.

In the face of that brand of total obstruction, senators are well justified to turn to the missing witness rule and draw the adverse inference.

Alternatively, the Senate can solve this problem. We can issue subpoenas. We have an able chief justice sitting as our presiding officer to settle evidentiary disputes. But if my Republican colleagues decide a full and fair trial is not in the interest of the Senate, the law gives us a roadmap to fill in the resulting gaps: We can draw adverse inferences. In such circumstances, "[s]ilence then becomes evidence of the most convincing character," as Justice Harlan Stone noted in the high court's 1939 ruling, Interstate Circuit v. United States.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse represents Rhode Island in the U.S. Senate. A former Rhode Island attorney general and U.S. attorney, Whitehouse serves on the Senate Judiciary, Budget, Finance, and Environment and Public Works committees.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Marble Palace Blog: Supreme Court Books You Should Read in 2025

Trending Stories

- 1Avantia Publicly Announces Agentic AI Platform Ava

- 2Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

- 3Joint Custody Awards in New York – The Current Rule

- 4Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 5Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.