DC Circuit Throws Out Lawsuit for Don McGahn's Testimony, in Major Loss for House

The 2-1 panel sided with the Justice Department's argument that the House cannot go to court to resolve "this kind of interbranch information dispute."

February 28, 2020 at 04:47 PM

7 minute read

Former White House Counsel Don McGahn (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

Former White House Counsel Don McGahn (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi/ALM)

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejected the House Judiciary Committee's bid to compel testimony from former White House counsel Don McGahn, a significant blow to the House and its legal fights.

In a 2-1 opinion, Judges Thomas Griffith and Karen LeCraft Henderson sided with the Justice Department's argument that the House cannot go to court to resolve "this kind of interbranch information dispute."

Judge Judith Rogers filed a dissenting opinion.

The highly anticipated ruling is sure to prove significant in the House's myriad other legal fights against the Trump administration. At least one lower court judge has pointed to the McGahn decision as likely informing his own opinion in a bid for President Donald Trump's federal tax returns.

Minutes after the McGahn decision landed, that jurist, U.S. District Judge Trevor McFadden, set a hearing for next Thursday on the House's motion to lift the stay he placed on the case.

Both the D.C. Circuit and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit have upheld congressional subpoenas for Trump's financial records from third parties. This is the first time the House has suffered a significant loss in one of the subpoena fights.

At the heart of the McGahn case is Trump's claim that the former White House counsel is "absolutely immune" from testimony. U.S. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson had rejected the concept in a ruling last year, but Friday's majority opinion did not rule on the merits of the claim.

Griffith, a former Senate legal counsel, on Friday echoed the Justice Department's warnings during oral arguments in January that involving the courts in the fight could politicize the judiciary.

"Interbranch disputes are deeply political and often quite partisan," he wrote in the opinion. "If we throw ourselves into 'a power contest nearly at the height of its political tension,' we risk seeming less like neutral magistrates and more like pawns on politicians' chess boards."

The judge further wrote that if the Judiciary Committee "can enforce this subpoena in the courts, chambers of Congress (and their duly authorized committees) can enforce any subpoena." And he argued the judiciary may repeatedly find itself at the heart of handling informational disputes, pointing to the House filing a lawsuit over documents relating to the failed attempt to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census one day after a district court judge upheld the McGahn subpoena.

"The walk from the Capitol to our courthouse is a short one, and if we resolve this case today, we can expect Congress's lawyers to make the trip often," Griffith wrote, citing House lawyers' promise that if McGahn invoked privilege during testimony, they would also go to court to challenge that.

Instead of going to court to enforce subpoenas, Griffith pointed to other tools in Congress' possession, like withholding appropriations or refusing to confirm Trump nominees.

"If federal courts were to swoop in to rescue Congress whenever its constitutional tools failed, it would not just supplement the political process; it would replace that process with one in which unelected judges become the perpetual 'overseer[s]' of our elected officials," Griffith wrote. "That is not the role of judges in our democracy, and that is why Article III compels us to dismiss this case."

Henderson also filed a concurring opinion, in which she agreed with Griffith that the committee lacked standing to bring forward this suit, but did not believe Congress could never go to court in any interbranch dispute.

She also criticized the "absolute immunity" claim, calling it "a step too far."

"Even setting aside the shaky foundation of testimonial immunity, a categorical refusal to participate in congressional inquiries strikes a resounding blow to the system of compromise and accommodation that has governed these fights since the republic began," Henderson wrote. "Political negotiations should be the first—and, it is hoped, only—recourse to resolve the competing and powerful interests of two coequal branches of government."

In a dissenting opinion, Rogers called the majority's ruling "extraordinary" and warned that it would have lasting and damaging consequences for congressional oversight.

"Exercising jurisdiction over the committee's case is not an instance of judicial encroachment on the prerogatives of another Branch, because subpoena enforcement is a traditional and commonplace function of the federal courts," she wrote. "The court removes any incentive for the executive branch to engage in the negotiation process seeking accommodation, all but assures future presidential stonewalling of Congress, and further impairs the House's ability to perform its constitutional duties."

The panel heard arguments over the subpoena in early January, days after the House impeached Trump but before the Senate impeachment trial began.

The GOP-held Senate has since acquitted Trump on both articles of impeachment for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, in relation to his hold on Ukrainian military aid while pushing for investigations into the Bidens.

House lawyers, represented by Megan Barbero, argued the testimony is necessary evidence as the Senate prepares for trial. And she echoed a brief filed by House lawyers days earlier that said McGahn's testimony could open the door to further articles of impeachment against Trump.

Justice Department attorney Hashim Mooppan argued the matter wasn't an issue for the court at all. Instead, he told the judges, ruling on the testimony would insert the courts into an ongoing impeachment proceeding that only Congress can conduct.

He claimed that could undermine public trust in the federal judiciary as an impartial adjudicator.

Griffith sounded wary of the court's authority to rule in the case. He pointed to other political tools that lawmakers could use to obtain McGahn's testimony, such as blocking appropriations.

But Rogers sounded like she wasn't buying Griffith's argument, noting that such an effort might also require agreement with the Senate, which features a different political makeup and agenda from the House.

Jackson, the district court judge in the case, ruled last year that McGahn could be compelled to testify before the House Judiciary Committee, rejecting the Trump administration's argument that such high-level officials, even former or currently serving in the administration, have "absolute immunity" from such testimony.

The judge labeled that argument "a proposition that cannot be squared with core constitutional values, and for this reason alone, it cannot be sustained."

The House sought quick enforcement of the subpoena, but the D.C. Circuit granted an administrative stay of the district court ruling as it weighed the case.

McGahn, now with Jones Day, witnessed several potential acts of obstruction of justice as laid out in special counsel Robert Mueller's report.

Obstruction of justice was not included as one of the two articles of impeachment passed against Trump. But the obstructive actions were cited as being part of a pattern of behavior by Trump, and further reason he should be removed from office.

The impeachment proceeding focused on Trump's efforts to push Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden, while withholding military aid from the country.

The D.C. Circuit also heard arguments the same day in early January on whether the House committee could obtain grand jury materials redacted from Mueller's report.

Read the opinion:

Read more:

DC Circuit Tosses Democrats' Emoluments Claims Against Trump and His Hotel

Judge Said He Expects Quick DC Circuit Ruling on McGahn in Pausing Trump Tax Returns Fight

DOJ Tells 'Unelected and Unaccountable' Judges to Stay Out of Fight for McGahn Testimony

Things Got Pretty Weird Between Neomi Rao and Doug Letter During the Mueller Grand Jury Hearing

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Government Attorneys Face Reassignment, Rescinded Job Offers in First Days of Trump Administration

4 minute read

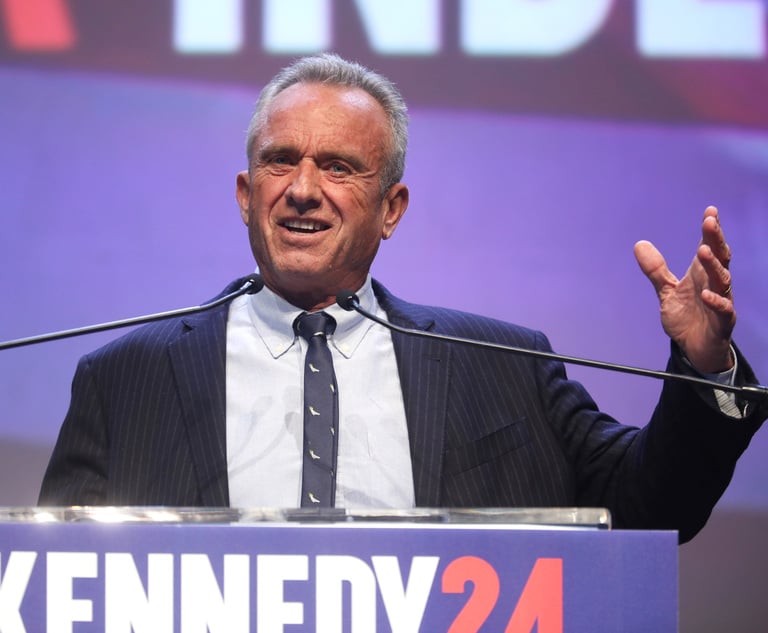

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Am Law 200 Firms Announce Wave of D.C. Hires in White-Collar, Antitrust, Litigation Practices

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250