Judge Spurns DOJ's Push to Hold Russian Company in Contempt in Mueller Case

"Based on the record before me, I don't that that you've met your burden" to hold Concord in contempt, U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich told prosecutors Thursday.

March 05, 2020 at 11:20 AM

4 minute read

Dabney Friedrich appears for her confirmation hearing in 2017. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM)

Dabney Friedrich appears for her confirmation hearing in 2017. (Photo: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM)

A federal judge on Thursday declined to hold a Russian company in contempt in a case brought by former Special Counsel Robert Mueller III, ruling that prosecutors had not proved the firm spurned a demand for records ahead of its upcoming trial.

At a brief hearing in Washington's federal trial court, U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich said she believed the Russian company, Concord Management and Consulting, had been in possession of the subpoenaed documents "at one time" in the past. But she said it was not clear Concord remained in possession of the records "at this point."

"Based on the record before me, I don't think that you've met your burden" to hold Concord in contempt, Friedrich told prosecutors.

Concord was charged in early 2018 with funding a scheme to sow discord in the U.S. electorate leading up to the 2016 election, in an election interference operation that allegedly featured Russians posing as Americans on social media.

Of the 13 Russian individuals and three Russian companies charged by Mueller's team, Concord is so far the only one that has answered to the charges in Washington federal court, where lawyers from Reed Smith have defended the firm. The prosecution is now being handled by a team from the U.S. attorney's office in Washington, including Adam Jed, a former member of Mueller's office.

Friedrich's ruling came a day after Concord's owner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian businessman known by the nickname "Putin's chef," claimed in a court filing that the company had fully complied with trial subpoenas seeking internet protocol addresses and financial records, among other documents.

Prigozhin, who was among 13 Russians charged with conspiring with Concord and other companies to interfere in the 2016 election, said Concord has a policy of storing emails and various other records for no more than three months.

"Concord's recordkeeping practices must be understood in the context of Russian, not American, practices, and Concord's actual recordkeeping is effected with due account of the fact that Concord has been the victim of several cyberattacks and has reason to expect future cyberattacks from the United States government and third parties," Prigozhin wrote, in a court filing that was translated from Russian into English.

Prigozhin said he was unable to identify the IP addresses used by Concord. And he claimed there were no records of Concord transferring money to the Internet Research Agency, another Russian company charged with influencing the 2016 election in support of Donald Trump.

Friedrich had said earlier in the week that she thought there was a "strong likelihood" that Concord had failed to comply with the subpoena. At the same hearing, Jed said Concord was in contempt and asked that the judge impose a daily fine on the company—a sanction that would have been largely symbolic given that the company is based in Russia.

As Friedrich's decision became clear Thursday, Jed made a last-ditch bid to salvage the government's push for Concord to be held in contempt. Jed offered to provide Friedrich with classified information, in a closed-door session, that he said would be "relevant to the court's determination of whether Concord is in contempt."

When asked whether the prosecutors were questioning the veracity of Prigozhin's court filing, Jed demurred, indicating he was limited in what he could say in an open court proceeding. Friedrich declined to meet privately, instead telling Jed that prosecutors could provide additional information in a request for her to reconsider holding Concord in contempt.

Without convincing evidence that Concord has the subpoenaed records, Friedrich said she was "not inclined" to hold the company in contempt.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

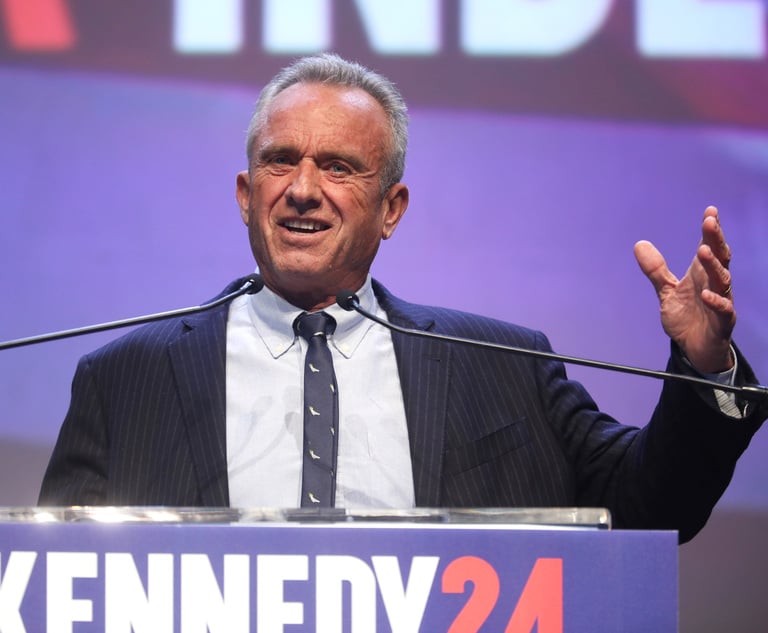

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

3rd Circuit Nominee Mangi Sees 'No Pathway to Confirmation,' Derides 'Organized Smear Campaign'

4 minute read

Judge Grants Special Counsel's Motion, Dismisses Criminal Case Against Trump Without Prejudice

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250