What the Legal Cases Over Ebola Quarantines Mean for Coronavirus

Norman Siegel and Steven Hyman, the attorneys who represented a Maine nurse in the legal fights over a 2014 quarantine order for Ebola, predicted that few civil liberty claims filed over coronavirus restrictions would hold up in court.

March 31, 2020 at 05:58 PM

6 minute read

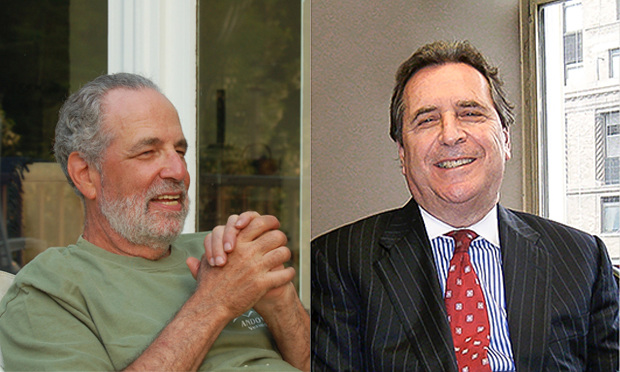

(L to R) Steven Hyman of McLaughlin & Stern and Norman Siegel, the former head of NYCLU, Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans, New York. (Courtesy photo)

(L to R) Steven Hyman of McLaughlin & Stern and Norman Siegel, the former head of NYCLU, Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans, New York. (Courtesy photo)

Attorneys who previously worked on legal challenges over an Ebola quarantine in the United States say the restrictions adopted in response to COVID-19 are likely to hold up in court, as long as they're in line with public health guidelines.

Norman Siegel, the former head of the New York Civil Liberties Union and now with Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans, and Steven Hyman, chair of McLaughlin & Stern's litigation department, represented Maine nurse Kaci Hickox as she faced quarantines in the U.S. after returning in 2014 from treating Ebola patients in Sierra Leone.

Hickox was quarantined for 80 hours in an isolation tent in New Jersey, and then faced a 21-day state-ordered quarantine in Maine over fears she could spread the virus. A Maine judge sided with Hickox in easing the restrictions placed on her, ruling she simply had to monitor her symptoms.

In 2015, Hickox filed a federal lawsuit against New Jersey officials over her quarantine there, and walked away in 2017 with a settlement that guaranteed rights to patients in New Jersey if they too were quarantined over the virus.

As states and federal officials issue orders and guidelines aimed at preventing the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the two attorneys who represented the nurse said the civil liberties questions presented by Hickox's differ greatly from those triggered by the coronavirus.

Ebola only becomes contagious once someone has symptoms, whereas coronavirus can be spread while an individual doesn't have symptoms, which the lawyers said means more drastic measures can be taken. Hickox was not symptomatic when she returned to the U.S.

Both lawyers, who have a wealth of experience in civil liberties cases, predicted few legal complaints would be made over the coronavirus-linked restrictions. If any did emerge, they said it was unlikely a court would uphold the challenge as long as the challenged policy was in line with public health advisories at the time it was issued.

"The balance is between public health, public safety, and individual rights to liberty, and it is different for the coronavirus, based on what we now know, as opposed to Ebola," Siegel said. "And what that results in, is it makes it more difficult to challenge the restrictions or limitations on the individual right to liberty that are accruing all over the country today."

To enforce then-Maine Gov. Paul LePage's order requiring Hickox to stay in her home for 21 days—the incubation timeline for Ebola—state officials petitioned a Maine state district court judge to issue a judgement that would have Hickox comply with the order.

At first, Judge Charles C. LaVerdiere ordered Hickox to stay away from public places and maintain a three-foot distance from others. But one day later, he lifted some of the restrictions, while still ordering Hickox to remain in contact with public health authorities on monitoring her symptoms.

"The state has not met its burden at this time to prove by clear and convincing evidence that limiting respondent's movements to the degree requested is 'necessary to protect other individuals from the dangers of infection,' however," LaVerdiere wrote. "According to the information presented to the court, respondent currently does not show any symptoms of Ebola and is therefore not infectious."

The judge did note the public fears surrounding Ebola, which had very little presence in the United States. He urged Hickox to keep those in mind during the remaining incubation period, even if those concerns stem from "misconceptions, misinformation, bad science and bad information."

"The court is fully aware that people are acting out of fear and that this fear is not entirely rational. However, whether that fear is rational or not, it is present and it is real," the judge wrote. "Respondent's actions at this point, as a health care professional, need to demonstrate her full understanding of human nature and the real fear that exists. She should guide herself accordingly."

Hyman, who is based in New York but has traveled to Vermont due to the pandemic, said the decisions being made around Hickox's case were "politically driven, not medically driven."

"Mainly Gov. [Chris] Christie and then Gov. LePage of Maine, who were making the decisions irrespective of what the CDC guidelines were. They were playing off the fear, not off of medical necessity," Hyman said.

However, the attorney said he did not believe the same situation was playing out today with respect to the coronavirus. Hyman said voices like Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, are helping to guide officials to implement appropriate restrictions in response to the virus.

Siegel, speaking from quarantine in his New York City apartment, said Hickox stressed to him the importance of having scientific evidence in implementing restrictions over public health concerns.

After Hickox sued the New Jersey officials in 2015 over her forced quarantine, the parties settled with the agreement that the state would adopt a "patient's bill of rights" for other Ebola quarantines. Those protections include the right to challenge quarantine orders, have legal assistance, be given prior notice of hearings, communicate with others and a guarantee to privacy, as long as it doesn't interfere with vital public health interests.

Both Siegel and Hyman said those protections are only offered in cases of Ebola. But Siegel said the CDC appears to have adopted several of those measures in cases of federal quarantines.

According to a 2018 Emory Law Review article, the Department of Health and Human Services formally adopted the new regulations in 2017, and they offer due process protections like the right to legally contest a quarantine order and to have counsel appointed if an individual cannot obtain an attorney.

Siegel said that while public health officials should lead the charge in responding to the pandemic, he said he believed he had a role to play as well in educating the public about the public health dangers caused by the pandemic. He said he's received calls from some interested in challenging restrictions, but indicated that he was unlikely to take on any of those cases.

"I don't think we have panic yet," Siegel said. "But there is fear."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Something Else Is Coming': DOGE Established, but With Limited Scope

Supreme Court Considers Reviving Lawsuit Over Fatal Traffic Stop Shooting

US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

3 minute read

US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1SurePoint Acquires Legal Practice Management Company ZenCase

- 2Day Pitney Announces Partner Elevations

- 3The New Rules of AI: Part 2—Designing and Implementing Governance Programs

- 4Plaintiffs Attorneys Awarded $113K on $1 Judgment in Noise Ordinance Dispute

- 5As Litigation Finance Industry Matures, Links With Insurance Tighten

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250