An 'Immodest Proposal': Bar Exam Requires Innovative Accommodations Amid Pandemic

Graduating students and desperate citizens could face stark realities if recent law graduates are placed into a prolonged professional coma.

April 02, 2020 at 01:25 PM

6 minute read

As bar leaders and examiners across the nation collectively face the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, I write with an "immodest proposal."

In his 1729 essay "A Modest Proposal," Jonathan Swift ironically proposed that poor Irish toddlers be fattened and sold as food for the wealthy, to control overpopulation and unemployment and improve the economy. In writing, he hoped to shock the policymakers of his time to move beyond simplistic and ineffectual responses to the Irish plight. However, I fear that Swift's description is all too accurate in describing how bar licensing authorities and senior bar leaders are approaching the COVID-19 pandemic as it affects graduating law students.

In using this analogy my point is to remind decision-makers of the stark realities facing graduating students and desperate citizens if recent law graduates are placed into a prolonged professional coma with crippling adverse effects. Let's look those realities in the eye.

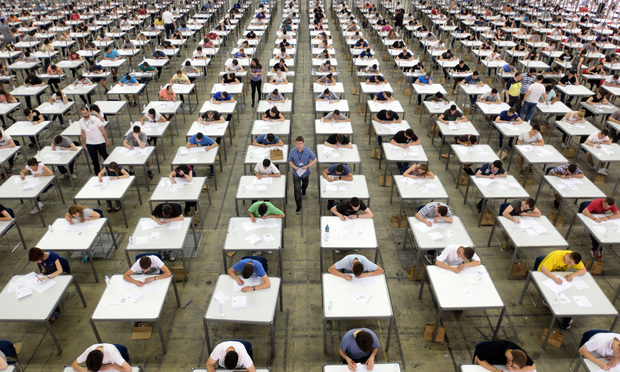

While several states have already decided to postpone their upcoming bar exams to fall, it's worth noting that a traditional September bar exam may not be viable. Unfortunately, we face a future in which COVID-19 may result in ongoing limitations on public assemblies, particularly if a second wave of infections materializes. The upshot would be a second rescheduling, likely in February, with other solutions harder to achieve because of lost time.

Further, a September—or later—bar exam ignores the costs to students. Graduating students have no ready way to secure the funds they will need to survive for the added months before the proposed September 2020 rescheduled bar exam. These costs are significant: bar prep courses, living costs and lost wages for those displaced from part-time jobs. Mental health costs will also rise, as the stress of caretaking responsibilities and uncertainty about the future cause anxiety to grow.

Preparation for current bar examinations takes focus and opportunity, and a delay will affect the least privileged the worst. Many nonaffluent students will have no recourse but to cram in close quarters with family members as they study and shelter in place. The stakes for bar passage are higher than ever for many, given debt loads and uncertain job opportunities. Students of color, first-generation college graduates and those with limited financial means face the greatest risks.

Finally, delayed licensure will deprive citizens of greatly needed legal assistance. Along with this public health emergency comes an unimaginable flood of legal problems concerning estates, housing, unemployment, consumer debt, family law, domestic violence and the survival of small businesses. Recent law graduates possess strong technical skills and practice capacity based on experience with clinics, externships and pro bono activities. We can't afford to delay deploying their skills and energy to meet citizens' enormous needs.

So, what should happen next?

First, these industry players need to recognize the factors that are impeding meaningful responses. Law is a conservative profession and client protection is important. But the impulse to delay seems to run deeper. Senior lawyers often assume that recent graduates' experiences with bar exams today are the same as their own in years past. It's not—it's a different exam, there are much higher stakes given student debt loads, and the pandemic makes preparation excruciatingly difficult. Licensing authorities are committed to fairness and test security but are also financially and emotionally invested in existing bar exam practices. We can't let our blind spots distract us from finding real solutions now.

Once some of these issues are identified, it's time to mitigate immediate problems through supervised practice rules. The New York Court of Appeals last Friday was the first jurisdiction to formally announce its intent to hold an early September bar exam. It also said it would explore adopting practice rules that would allow recent graduates to engage in temporary supervised practice in private and public settings, subject to yet-to-be-established criteria. Perhaps a model practice rule could be adopted to facilitate subsequent licensure and smooth the way forward nationally. But more needs to be done in light of the financial impact of truncated wages and the dislocation of requiring candidates to take a full bar exam after even greater delay.

Bar leaders should also consider adopting an emergency provisional licensing system. For example, grant registered bar candidates a one-year provisional license that functions as an enhanced training and evaluation period. For an initial four- to six-month period, candidates would work under the mentorship and supervision of an experienced licensed attorney who would be expected to complete and submit a detailed assessment of the graduate's competence (something currently expected of law school clinical and externship supervisors). If certified by the supervisor as demonstrating core competence requirements, the candidate would then complete a truncated bar exam that uses a closed universe library and practice-oriented questions (similar to systems being developed in Canada and England). If the candidate demonstrated requisite competence on both the supervisor's evaluation and the truncated bar exam, and satisfied character and fitness requirements, they would receive a general license. If they failed to satisfy either of these requirements, they would have the opportunity to continue working under a provisional license for another six months, receive another comprehensive supervisor evaluation, and retake the truncated exam. If they failed after a year to satisfy these requirements, they would have to sit for the regular bar exam before receiving a general license to practice without supervision.

There are other options that deserve attention as well, such as the diploma privilege (now used in Wisconsin and previously employed by California after the 1906 earthquake and during World War II). Remote proctoring is increasingly used in educational settings and warrants immediate, intensive exploration. Developing longer-term, limited-licensing options in specialized high-need areas may also be worth exploring.

Swift used powerful satire to jolt decision-makers out of deadly lethargy. But let's not incapacitate or cannibalize the next generation of lawyers eager to meet crucial citizen needs. Let's find innovative approaches to licensure that foster justice instead.

Judith Welch Wegner is Burton Craige Professor Emerita, UNC School of Law. She is a co-author of a recent working paper, "The Bar Exam and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Need for Immediate Action."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Switching Positions: US Solicitors General and Climate Change Lawsuits

6 minute read

Jimmy Carter’s 1974 Law Day Speech: A Call for Lawyers to Do the Public Good

14 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Attorney Sanctioned $9K for Revealing Nude Photos, Other Info in Court Filing

- 2Shifting Battlegrounds in Administrative Law, From Biden to Trump II

- 3Bar Report - Jan. 13

- 4Newsmakers: Robert Collins, Barron Wallace Elected to Bracewell’s Management Committee

- 5Navigating the Shifting Sands of E-Discovery and Information Governance in 2025

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250