New Book 'Shortlisted' Spotlights 9 Women Passed Over for Supreme Court

"Florence Allen, the first woman to start appearing on presidential short lists, is absolutely a standout. President Roosevelt missed an enormous opportunity," Renee Knake of the University of Houston Law Center, an author of the new book, says.

May 12, 2020 at 06:15 PM

4 minute read

U.S. Supreme Court building on April 23, 2019. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

U.S. Supreme Court building on April 23, 2019. Credit: Diego M. Radzinschi / ALM

Before Sandra Day O'Connor was nominated and confirmed to a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court in 1981, a handful of presidents, going back to Franklin Roosevelt, considered nine women for high court vacancies.

The new book "Shortlisted: Women in the Shadows of the Supreme Court"—from Renee Knake of the University of Houston Law Center and Hannah Brenner Johnson, vice dean of California Western School of Law in San Diego—"tells the overlooked stories" of those women. The book arose out of the authors' study of media coverage of the nominations of Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

The National Law Journal spoke with Knake about how that study spurred a book about the nine women and a short-listing phenomenon that exists in the legal and corporate worlds.

How did the media study inspire the short-listed book?

We came across an Oct. 14, 1971, article in the New York Times, appearing above the fold, written about Mildred Lillie. It was the first time we were able to uncover such a public airing of a short list. Nixon had six names. What was most interesting was who the heck was Mildred Lillie and how many other women were short-listed before Sandra Day O'Connor was nominated? That was really the first seed planted for this book.

What is the short-listing phenomenon?

Richard Nixon is the most obvious example. He puts out this list [of possible Supreme Court nominees] and it's circulated in the media. But in tapes from the Oval Office, we learned, he didn't think women should vote. He later says in a speech, "I know you wanted a female justice but at least we considered women." They like to show their short list includes diversity and yet we know from statistics on who makes up leadership, women and minorities are not moving into positions of leadership and power in numbers reflecting their numbers entering law. It lets them off the hook to select a nondiverse candidate.

Do any of the nine women stand out in particular with you?

Florence Allen, the first woman to start appearing on presidential short lists, is absolutely a standout. President Roosevelt missed an enormous opportunity. He put her on the court of appeals after she had secured herself a seat on the Supreme Court of Ohio and she did that because she was so active in women's suffrage. She went out and campaigned for women's right to vote and once it was secured, she turned around and asked them to vote for her. The breadth of experience she would have brought to the Supreme Court would have been really profound.

And Amalya Kearse, the only woman of color. Being a minority woman, she had, like all women in that cohort, initially struggled to find employment. She is a tangible example of how a process implemented by President Jimmy Carter—judicial commissions—can result in meaningful change.

Why did you go beyond telling the women's stories to offer eight strategies to surmount the short list?

We did not want to end up with a list that said if you do all eight strategies we'll have another woman on the Supreme Court. Our point is more what can we take from these women's lives that is still really relevant today?

Some of them are kind of obvious: law degrees. The women couldn't change the fact they were women and excluded from professional life so they went and obtained a qualification men had and which enabled them to enter professional life, to get a foot in the door. Find a mentor. Collaborate to compete—across political and ideological lines.

The book was 10 years in the making. Would you do it again knowing that commitment?

Even though we had other things going on, we couldn't let this story go, especially once I got into the archives of their lives. I couldn't believe their stories hadn't been told yet. I would do it again, absolutely.

Read more:

US Solicitor General's Office Snags Paul Weiss, Cooper & Kirk Lawyers

Gender Diversity Declines at US Solicitor General's Office

Cate Stetson Looks Ahead to Milestone of 100 Appellate Arguments

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

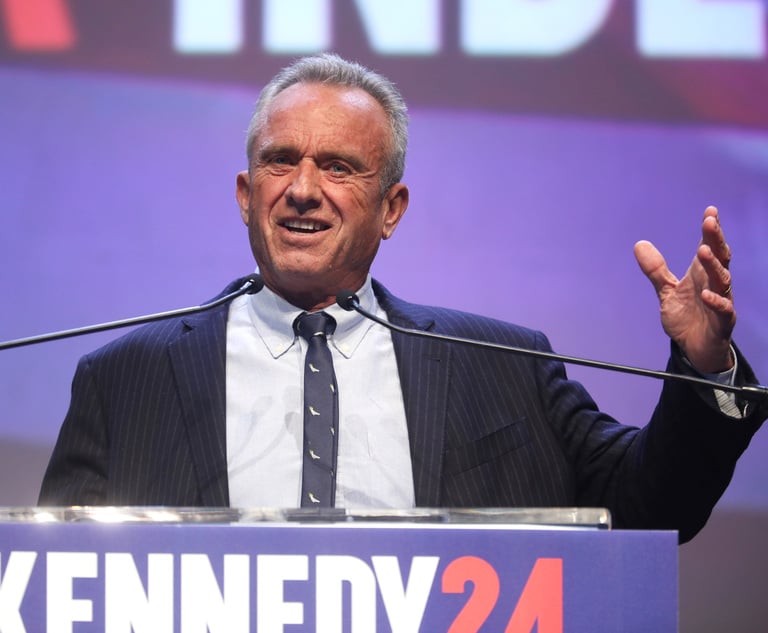

RFK Jr. Will Keep Affiliations With Morgan & Morgan, Other Law Firms If Confirmed to DHHS

3 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

3rd Circuit Nominee Mangi Sees 'No Pathway to Confirmation,' Derides 'Organized Smear Campaign'

4 minute read

Judge Grants Special Counsel's Motion, Dismisses Criminal Case Against Trump Without Prejudice

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250