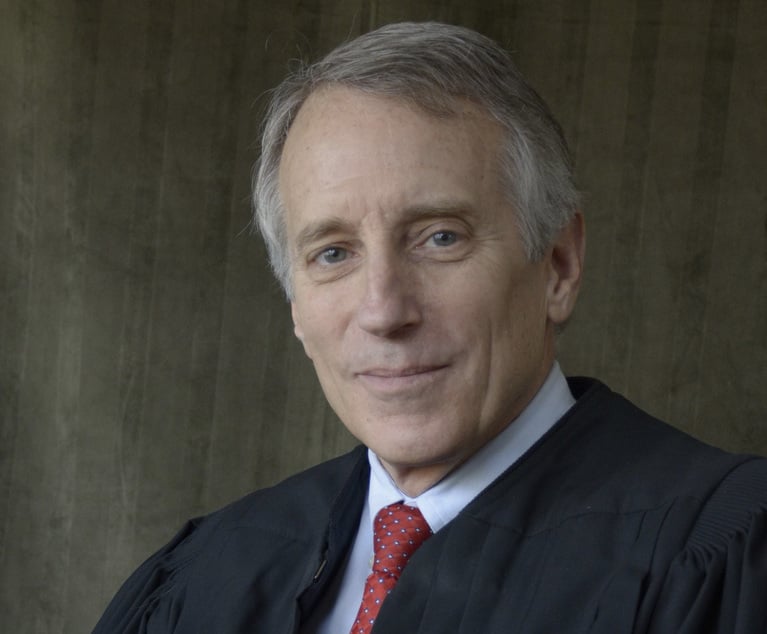

Portrait of Gilbert Merritt Jr., chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, by Michael Shane Neal. Credit: Michael Shane Neal via Wikipedia

Portrait of Gilbert Merritt Jr., chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, by Michael Shane Neal. Credit: Michael Shane Neal via Wikipedia The Marble Palace Blog: 6th Circuit Judge Merritt, Once Considered for SCOTUS Seat, Has Died at Age 86

Appeals Judge Gilbert Merritt Jr., who died on Jan. 17, is heralded as a "devoted champion of justice" and "a great mentor, boss, friend, and jurist."

January 20, 2022 at 10:06 AM

4 minute read

Thank you for reading The Marble Palace Blog, which I hope will inform and surprise you about the Supreme Court of the United States. My name is Tony Mauro. I've covered the Supreme Court since 1979 and for ALM since 2000. I semiretired in 2019, but I am still fascinated by the high court. I'll welcome any tips or suggestions for topics to write about. You can reach me at [email protected].

In 1993, Gilbert Merritt Jr., a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, was on President Bill Clinton's short list to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court when Byron White retired. But Merritt had strong competition for the seat: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer and Richard Arnold, among others.

Ginsburg got the nod (Breyer got it the next year), and Merritt remained comfortably on the Sixth Circuit, working from his Nashville chambers. After 44 years on the bench, Merritt died on Jan. 17 on his 86th birthday.

Jeff Sutton, chief judge of the Sixth Circuit, praised Merritt as "a brilliant jurist, a devoted champion of justice, a beloved colleague, and a local, regional, and national leader of the federal judiciary for forty years. … He saw all sides to every case; he treated everyone with respect; he was kind when kindness was called for, bold when boldness was due."

Keel Hunt, author of a forthcoming biography of Merritt, said, "To me, the real measure of the man—apart from his deep scholarship and long judicial record—was the genuine respect he had from both colleagues on the court and also the dozens of women and men who worked as law clerks in his chambers over 40-plus years."

Michael Gerhardt, professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law who clerked for Merritt, said the judge was "a great mentor, boss, friend, and jurist."

Merritt was an advocate for sentencing reform, and an opponent of the death penalty. "Judge Merritt understood that the law, particularly as it applies to the death penalty, has too often become a procedural mechanism to maintain convictions and death sentences, even when fairness and truth get in the way," said Stacy Rector, executive director of Tennesseans for Alternatives to the Death Penalty.

During the landmark Bush v. Gore Supreme Court case in 2001, Merritt played a brief role when The New York Times reported that Justice Clarence Thomas' wife Virginia was working for the conservative Heritage Foundation. Someone in the Gore campaign suggested that the reporter contact Merritt, who happened to be a longtime friend of the Gore family, to comment on whether Thomas should be recused because of his wife's relationship with Heritage.

Merritt told the reporter that "The spouse has obviously got a substantial interest that could be affected by the outcome. I think [Thomas] would be subject to some kind of investigation in the Senate." Merritt did not launch a complaint against Thomas.

In 1996, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist appointed Merritt to chair the executive committee of the Judicial Conference, the policy arm of the federal judiciary. It was a period when the conference was debating whether cameras should be allowed to broadcast court proceedings.

In a 1998 article, I quoted Merritt as someone who supported camera access, especially at the appeals court level where concerns about the impact on jurors and witnesses is not an issue because jurors and witnesses don't attend appellate proceedings.

But Merritt, known for respecting both sides of an issue, said he understood why judges were against camera access, even when a three-year experiment was viewed as a success for broadcasting proceedings.

"There's a sort of nuanced, Federalist Papers kind of feeling among federal judges that we're supposed to be the last bastion of independence, not responding to majority will, and that carries over to the camera question," he told me. "It's not such a bad thing."

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

DC Circuit Keeps Docs in Judge Newman's Misconduct Proceedings Sealed

Who Are the Judges Assigned to Challenges to Trump’s Birthright Citizenship Order?

‘Undermines the Rule of Law’: Retired US Judges Condemn Trump’s Jan. 6 Pardons

'If the Job Is Better, You Get Better': Chief District Judge Discusses Overcoming Negative Perceptions

Trending Stories

- 1Big Law's Middle East Bet: Will It Pay Off?

- 2'Translate Across Disciplines': Paul Hastings’ New Tech Transactions Leader

- 3Milbank’s Revenue and Profits Surge Following Demand Increases Across the Board

- 4Fourth Quarter Growth in Demand and Worked Rates Coincided with Countercyclical Dip, New Report Indicates

- 5Public Notices/Calendars

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250