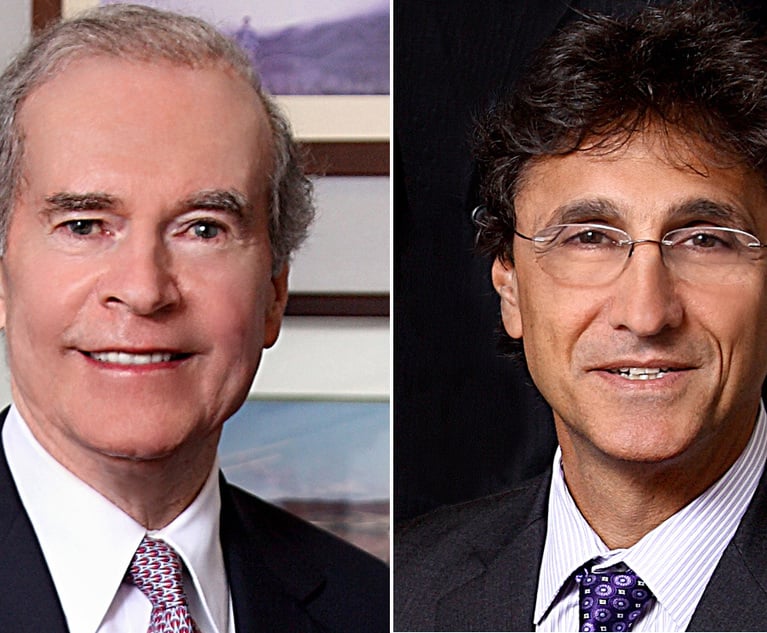

Revisiting New York Case Law on Loss of Chance: Part 2

Medical Malpractice columnists Thomas A. Moore and Matthew Gaier write: In addition to delays in diagnosing cancer, cases involving delays in diagnosing or treating cerebral vascular accidents such as strokes or bleeds commonly give rise to claims for loss of chance.

June 05, 2017 at 02:04 PM

13 minute read

The initial installment of this column examined the history of recovery for loss of chance in New York. Four years ago, we reviewed the manner in which recovery for loss of chance has been applied in cases involving delays in diagnosing cancer. We now review such recovery in cases that do not involve delays in diagnosing cancer.

Before turning to the substance of those cases, it is helpful to set forth the legal principles applicable to recovery for a loss of chance. The Fourth Department's decision in Clune v. Moore, 142 A.D.3d 1330 (4th Dept. 2016), provides a concise and comprehensive articulation of those principles, stating:

Where, as here, the plaintiff alleges that the defendant negligently failed or delayed in diagnosing and treating a condition, a finding that the negligence was a proximate cause of an injury to the patient may be predicated on the theory that the defendant thereby “diminished [the patient's] chance of a better outcome,” in this case, survival. In that instance, the plaintiff must present evidence from which a rational jury could infer that there was a “substantial possibility” that the patient was denied a chance of the better outcome as a result of the defendant's deviation from the standard of care. However, “[a] plaintiff's evidence of proximate cause may be found legally sufficient even if his or her expert is unable to quantify the extent to which the defendant's act or omission decreased the [patient's] chance of a better outcome … , 'as long as evidence is presented from which the jury may infer that the defendant's conduct diminished the [patient's] chance of a better outcome'.” (Extensive citations have been omitted in light of space constraints.)

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

CPLR Article 16 Apportionment And Dismissed Defendants Medical Malpractice

14 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Don’t Forget the Owner’s Manual: A Guide to Proving Liability Through Manufacturers’ Warnings and Instructions

- 2Newsmakers: Former Pioneer Natural Resources Counsel Joins Bracewell’s Dallas Office

- 3Quiet Retirement Meets Resounding Win: Quinn Emanuel Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan's Vimeo Victory

- 4Avoiding the Great Gen AI Wrecking Ball: Ignore AI’s Transformative Power at Your Own Risk

- 5A Lesson on the Value of Good Neighbors Amid the Tragedy of the LA Fires

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250