Notice of Claim Requirements in Suits Against Police Officers Revisited

Bradley M. Wanner and Andrew J. Orenstein discuss a unanimous Second Department decision which overturned the dismissal of a lawsuit against three police officers who were not named in the Notices of Claim. With departments now split, it will only be a matter of time before the Court of Appeals is asked whether claimants are required to name individual municipal employees in their Notices of Claim.

June 26, 2017 at 02:02 PM

7 minute read

In a recent unanimous decision, the Appellate Division, Second Department, overturned the dismissal of a lawsuit against three police officers who were not named in the Notices of Claim. The decision in Blake v. City of New York, 148 A.D.3d 1101 (2d Dept. 2017), overruled prior cases in the Second Department and came just 15 months after the First Department reached the opposite conclusion in Alvarez v. City of New York, 134 A.D.3d 599 (1st Dept. 2015). With this department split, it will only be a matter of time before the Court of Appeals is asked whether claimants are required to name individual municipal employees in their Notices of Claim.

Background

Blake stems from the arrest and indictment of the plaintiffs for their alleged involvement in an October 2008 shooting in Queens. After approximately 16 months in jail awaiting trial, a police informant who had positively identified the plaintiffs in two photo arrays recanted his identification and the charges were dismissed. The plaintiffs then filed lawsuits against, inter alia, the City of New York and five individual police officers for false arrest, malicious prosecution, and civil rights violations. Three of the named police officers, who were not identified in the Notices of Claim, moved for dismissal since they were not named in the Notices of Claim. Supreme Court granted dismissal on this basis and the plaintiffs appealed.

Decision

The Second Department held that the three police officers were not entitled to dismissal of the false arrest and malicious prosecution claims. The court began its analysis by acknowledging a split in the decisional law, noting that the First Department requires a municipal employee to be named in the Notice of Claim, see Alvarez, 134 A.D.3d 599; Tannenbaum v. City of New York, 30 A.D.3d 357 (1st Dept. 2006), whereas the Third and Fourth Departments do not. See Pierce v. Hickey, 129 A.D.3d 1287 (3d Dept. 2015); Goodwin v. Pretorius, 105 A.D.3d 207 (4th Dept. 2013).

Adopting the rationale of the Third and Fourth Departments, the Blake court adhered to a narrow interpretation of the statutory language of General Municipal Law §50-e(2), requiring the Notice of Claim to (1) be in a sworn writing; (2) provide the address of the claimant and his attorney; (3) set forth the nature of the claim, the time, place, and manner in which the claim arose; and (4) itemize the claimant's injuries and damages. The court held that it would not impose a requirement on claimants that is not specifically enumerated in the GML. In contrast to the First Department, the court characterized the purpose of the Notice of Claim as being solely to “notify the municipality, not the individual defendants” of a potential claim. See Blake, supra (citing Zwecker v. Clinch, 279 A.D.2d 572 (2d Dept. 2001).

The court also relied upon Scott v. City of New Rochelle, 44 Misc.3d 366 (Sup. Ct. 2014), which adopted the Fourth Department's reasoning, distinguishing the Second Department's decision in Matter of Rattner v. Planning Commission of the Village of Pleasantville, 156 A.D.2d 521 (2d Dept. 1989), because the issue was whether a Notice of Claim was required at all, not whether individual employees were required to be named therein. See Scott, supra. The court went on to approve the notion that the Notice of Claim is merely a vehicle by which to give a municipality an opportunity to investigate the facts and merits of a claim. See id.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

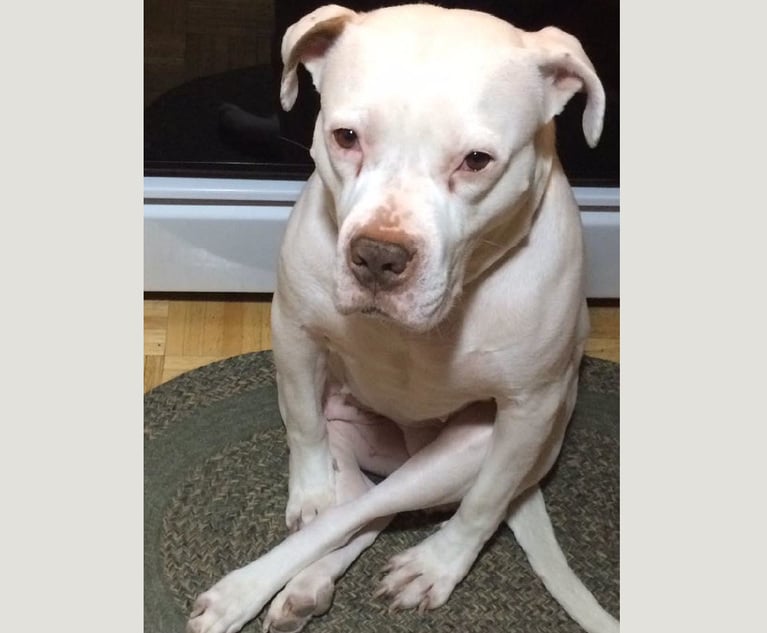

Decision of the Day: Court Rules on Judgment Motions Over Police Killing of Pet Dog While Executing Warrant

A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

13 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Dissenter Blasts 4th Circuit Majority Decision Upholding Meta's Section 230 Defense

- 2NBA Players Association Finds Its New GC in Warriors Front Office

- 3Prenuptial Agreement Spousal Support Waivers: Proceed With Caution

- 4DC Circuit Keeps Docs in Judge Newman's Misconduct Proceedings Sealed

- 5Litigators of the Week: US Soccer and MLS Fend Off Claims They Conspired to Scuttle Rival League’s Prospect

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250