The Emergency Room Exception for Vicarious Liability

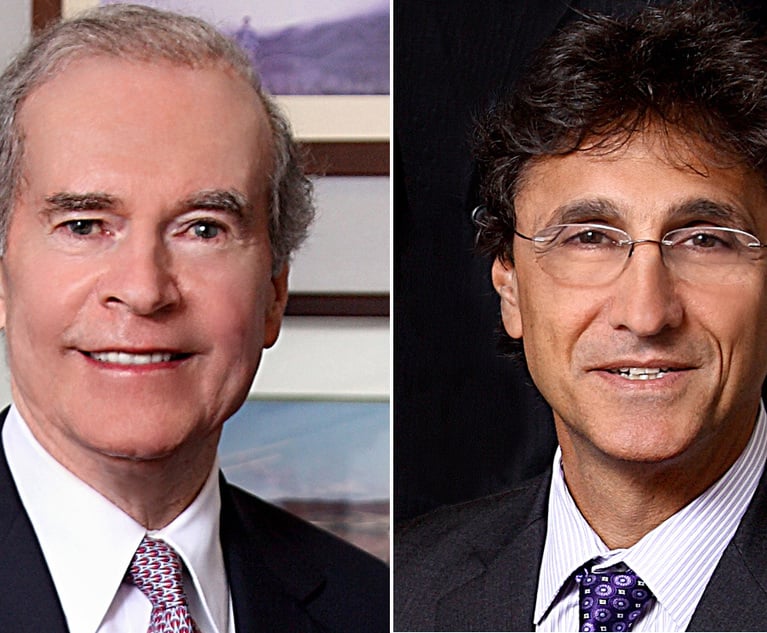

In their Medical Malpractice column, Thomas A. Moore and Matthew Gaier write: While it has long been recognized that a hospital is vicariously liable for the physicians it assigns to patients where a patient seeks treatment not from a particular physician, but from the hospital, some decisions have strictly imposed all of the requirements of ostensible agency. However, this circumstance is not purely one of ostensible agency. Rather, it is a distinct exception that involves aspects of both ostensible agency and agency-in-fact.

July 31, 2017 at 02:03 PM

15 minute read

It is an established general rule that hospitals are not liable for the malpractice of physicians who are not their employees. It is equally established that there are exceptions to that rule, the two most prominent of which are the ostensible agency theory and agency-in-fact or control theory. The body of law addressing these exceptions is voluminous and has developed some inconsistencies.

One circumstance in which this has occurred is where a patient seeks treatment not from a particular physician, but from the hospital. While it has long been recognized that the hospital is vicariously liable for the physicians it assigns to patients in that situation, some decisions have strictly imposed all of the requirements of ostensible agency. However, this circumstance is not purely one of ostensible agency. Rather, it is a distinct exception that involves aspects of both ostensible agency and agency-in-fact. In essence, the “hospital patient” or “emergency room” exception to the general rule is a hybrid of the two exceptions. This column examines the development of these vicarious liability exceptions.

History

The earliest decision finding vicarious liability for malpractice by a non-employee was Hannon v. Siegel-Cooper, 167 N.Y. 244 (1901). The plaintiff was injured during treatment rendered by a dentist at the defendants' department store. The store “represented and advertised itself as carrying on the practice of dentistry in one of its departments.” The store owners appealed from a verdict for the plaintiff. Citing “the general doctrine that a person is estopped from denying his liability for the conduct of one whom he holds out as his agent against persons who contract with him on the faith of the apparent agency,” the court held that “the plaintiff had a right to rely not only on the presumption that the defendant would employ a skillful dentist as its servant, but also on the fact that if that servant, whether skillful or not, was guilty of any malpractice, she had a responsible party to answer therefor in damages.”

A half-century later, in holding that hospitals may be liable under respondeat superior for physicians and nurses they employ, the court observed in Bing v. Thunig, 2 N.Y.2d 656 (1957) that “[t]he conception that the hospital does not undertake to treat the patient, does not undertake to act through its doctors and nurses, but undertakes instead simply to procure them to act upon their own responsibility, no longer reflects the fact,” and that “the person who avails himself of 'hospital facilities' expects that the hospital will attempt to cure him, not that its nurses or other employees will act on their own responsibility.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

CPLR Article 16 Apportionment And Dismissed Defendants Medical Malpractice

14 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Don’t Forget the Owner’s Manual: A Guide to Proving Liability Through Manufacturers’ Warnings and Instructions

- 2Newsmakers: Former Pioneer Natural Resources Counsel Joins Bracewell’s Dallas Office

- 3Quiet Retirement Meets Resounding Win: Quinn Emanuel Name Partner Kathleen Sullivan's Vimeo Victory

- 4Avoiding the Great Gen AI Wrecking Ball: Ignore AI’s Transformative Power at Your Own Risk

- 5A Lesson on the Value of Good Neighbors Amid the Tragedy of the LA Fires

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250