Authors Depict Discrimination Faced by Black Men at Every Stage of Criminal Justice System

The statistics are alarming. Black men are 2.5 times more likely to be arrested than whites, 21 times more likely to be killed by police and twice as likely to be unarmed when killed by police.

January 23, 2018 at 11:13 AM

6 minute read

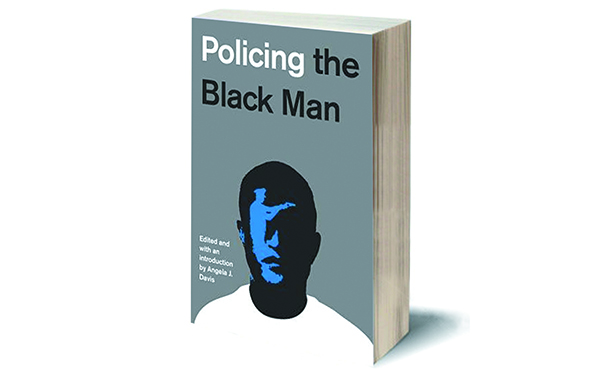

Policing the Black Man: Arrest, Prosecution and Imprisonment

Edited by Angela J. Davis

Pantheon Books, New York, 352 pages, $27.95

One of the great blessings of my New York City Bar Association membership was befriending the late Judge Sheila Abdus-Salaam who taught me that freedom is equality, empathy is a choice we make and acceptance of intolerance produces oppression.

Inequality, bias, empathy and oppression are major themes that dominate a new anthology edited by Professor Angela J. Davis, who has compiled eleven powerful essays that argue black men “are policed and treated worse than their similarly situated white counterparts at every step of the criminal justice system, from arrest through sentencing.”

The book draws attention to the disparities created by a “facially race-neutral system” that ostracizes offenders and stigmatizes blacks as criminals. In addition to identifying the root causes of this injustice, the book also examines the innovative ways enlightened public officials and scholars are tackling the problem. As such, the book makes a useful contribution to the national discussion that will produce change.

The statistics are alarming. Black men are 2.5 times more likely to be arrested than whites, 21 times more likely to be killed by police and twice as likely to be unarmed when killed by police. Meanwhile, black men constitute 34% of the American prison population and serve sentences that are 19.5% longer than white men for the same crime.

As chronicled by Professor Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010), one-third of the black men born in 2001 can expect to be incarcerated in their lifetimes, and the total number of black men in prison or jail, on probation, or on parole is roughly equal to the number enslaved in 1850. This “criminal caste system” tends to stigmatize black men for life, relegating them to a “second-class citizenship” of job discrimination, exclusion from voter rolls and jury service and disqualification from food stamps, public housing, health and welfare benefits and student loans.

In a masterful introductory essay, Bryan Stevenson, the director of Equal Justice Initiative and accomplished Supreme Court advocate, discusses the legacy of America's sordid history of racial injustice and terror. In so doing, Stevenson examines the connection between lynching, capital punishment and racial disparities in the implementation of the death penalty. As noted by the editor, Stevenson's essay “lays a solid foundation for the remainder of the book and is essential to the reader's understanding of how and why the American criminal justice system continues to police black men.”

The most insightful essay is written by Professor Katheryn Russell-Brown, who focuses on the phenomenon of “implicit bias,” the “unconscious bias that results from exposure to negative stereotypes and attitudes,” particularly in police interactions with black men.

Russell-Brown notes that psychologists have developed many tests to measure “hidden bias.” In one computer simulation, 50 police officers were tested on their decision to shoot, based on photos showing a person with either a gun or a neutral object. The study concluded that “officers were more likely to shoot if the unarmed suspect was black.”

On a hopeful note, however, the same study also concluded that “repeated viewings of the simulation led to an elimination of racial bias,” and multiple exposures to the simulation “shifted the officers' decision criteria for black suspects.”

As described by Russell-Brown, this and other similar studies have reached similar results: (1) police tend to respond in a racially-biased way toward blacks; (2) the decision to shoot is made more quickly when there is a black armed target; (3) police are more likely to see a black armed target where none exists and less likely to see a white one who does exist; (4) when targets do not match stereotypes, police take longer to decide when to shoot; (5) police show less implicit bias than members of the general public; and (6) a police officer's personal beliefs and contact with minority communities affects levels of implicit bias.

Russell-Brown also discusses how training and education is assisting law enforcement and courts to recognize and counter racial bias. A widely-used program, entitled “Fair and Impartial Policing,” teaches officers about “implicit bias, how it works, and how it may impact their decision-making skills regarding the use of force.” She further notes that California Attorney General Kamala Harris established in 2015 the first such certified training program on implicit bias and procedural justice, and in 2016 the Department of Justice began requiring implicit bias training for 28,000 federal law enforcement agents and prosecutors.

Russell-Brown also highlights the work of U.S. District Judge Mark Bennett to increase awareness about implicit bias. The judge has urged all criminal justice system decision-makers to take the Implicit Association Test, an online test that measures hidden bias and has been taken by 1.5 million people.

In a concluding essay by former John Jay College President Jeremy Travis and Professor Bruce Western, the authors note that the “great markers of racial injustice have been violence and poverty.” Noting that poor and under-educated blacks are now incarcerated at an unprecedented level, the authors state that changing how governments respond to crime is vital to reducing prison populations.

Like Professor James Forman, Jr. (in a 2012 edition of the New York University Law Review), Travis and Western posit that mass incarceration is detrimental to public safety, rather than necessary to secure it. Forman notes that New York City has reduced crime while also reducing the number of people sent to prison. Such progress will require the increased use of diversion and other alternatives, reducing the time served in prison, decreasing the number of parole revocations, making better use of probationary resources and increasing human capital investments in education.

As observed by Forman, America incarcerates too many people generally and too many blacks specifically, thus creating “second-class citizenship” for millions. Like Professors Alexander and Forman, this book demonstrates how our society's decision to heap shame and contempt on those who struggle and fail in a system designed to keep them locked up and locked out says far more about ourselves than it does about them.

Jeffrey M. Winn is a management liability attorney with Chubb, a global insurer, and a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'We Learn Much From the Court's Mistakes': Law Journal Review of 'The Worst Supreme Court Decisions, Ever!'

6 minute read

'Midnight in Moscow': A Memoir From the Front Lines of Russia's War Against the West

9 minute read

'There Are Heroes in Every Story': Review of 'The Eight: The Lemmon Slave Case and the Fight for Freedom'

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Court Holds Accident with Post Driver Was 'Bizarre Occurrence,' Dismisses Action Brought Under Labor Law §240

- 2Judge Recommends Disbarment for Attorney Who Plotted to Hack Judge's Email, Phone

- 3Two Wilkinson Stekloff Associates Among Victims of DC Plane Crash

- 4Two More Victims Alleged in New Sean Combs Sex Trafficking Indictment

- 5Jackson Lewis Leaders Discuss Firm's Innovation Efforts, From Prompt-a-Thons to Gen AI Pilots

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250