Standard for Pleading a Claim of Direct Patent Infringement: 'Sessler'

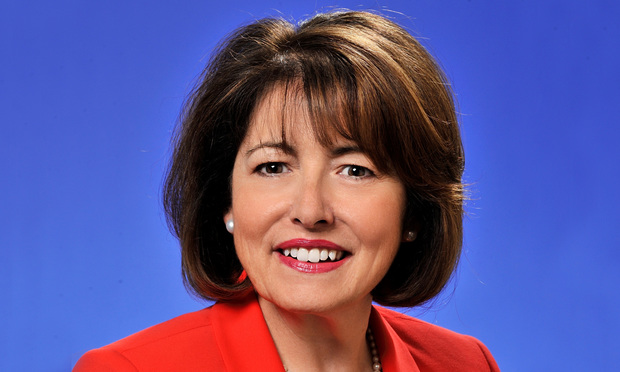

In her Western District Roundup, columnist Sharon M. Porcellio discusses the recent decision in 'L.M. Sessler Excavating', in which the court considered an issue of first impression: whether the pleading standard articulated in 'Twombly' and 'Iqbal' is the proper measure for pleading a claim of direct patent infringement.

January 25, 2018 at 02:46 PM

8 minute read

Last quarter, U.S. District Court Chief Judge Frank P. Geraci decided a patent infringement case in which he addressed the relationship between patent law and the applicable pleading standard under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. More specifically, in finding that the defendant had not infringed on the plaintiff's patent, the court considered an issue of first impression: whether the pleading standard articulated in Twombly and Iqbal is the proper measure for pleading a claim of direct patent infringement. See generally Bell Atlantic v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007); Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662 (2009).

Moreover, in the same quarter, Magistrate Judge Jeremiah J. McCarthy issued a Report and Recommendation in yet another patent case pending in the Western District. In his Report and Recommendation, Judge McCarthy found against the defendants. Shortly thereafter, the Federal Circuit decided a case which prompted Judge McCarthy to vacate his own Report and Recommendation.

Procedural History in 'Sessler'

In L.M. Sessler Excavating & Wrecking v. Bette & Cring, No. 16-CV-06534-FPG, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 171708, at *1 (W.D.N.Y. Oct. 17, 2017), L.M. Sessler Excavating and Wrecking (plaintiff), a New York corporation, brought an action for patent infringement against Bette & Cring (defendant), a New York Limited Liability Company, pursuant to Title 35 of the U.S. Code (which deals exclusively with patents). The plaintiff alleged that the defendant's activities in connection with its work on a New York State Thruway Department of Transportation contract infringed their U.S. Patent No. 6,155,649 (the '649 Patent), which protects a process for bridge demolition via a particular truck assembly. Id. at *2-3.

More specifically, the plaintiff claimed that the defendant directly infringed on their '649 patent, and also asserted that the defendant was liable on theories of induced and contributory infringement. Id. at *3-4. For all three grounds, the plaintiff further asserted that the defendants alleged infringement was willful. Id.

The defendant moved to dismiss the plaintiff's complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). Id. The plaintiff then filed an amended complaint and the defendant similarly moved to dismiss the amended complaint under 12(b)(6). Id. at *2. The court ultimately granted the motion to dismiss. Id.

Court's Analysis

In deciding this case, the court interpreted the relationship between both direct and indirect infringement claims and the 12(b)(6) pleading standard under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Direct Infringement Claim. The plaintiff first alleged that the defendant directly infringed and continued to infringe upon the '649 patent. Id. at *3. At the outset, the court noted that the issue of which pleading standard would apply to the plaintiff's direct infringement claim was unresolved within the Second Circuit, and consequently, that the court was deciding an issue of first impression. The court began its analysis by mentioning Rule 8(a)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which states:

[a] pleading that states a claim for relief must contain: (1) a short and plain statement of the grounds for the court's jurisdiction, unless the court already has jurisdiction and the claim needs no new jurisdictional support; (2) a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief; and (3) a demand for the relief sought, which may include relief in the alternative or different types of relief.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(a)(2). Specifically, the court noted that although both Iqbal and Twombly “clarified the basic contours of Rule 8(a)(2), courts remained divided as to the cases' effect on claims of direct patent infringement.” Id. at *6.

Before Dec. 1, 2015, courts maintained that Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 84 and accompanying Form 18 signaled the prevailing pleading requirement. Id. at *6. The former Rule 84 had provided that the pleading forms appended to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were sufficient and “illustrate[d] the simplicity and brevity” that the former rules had contemplated. Id. at *8 (citing Gradient Enters. v. Skype Techs. S.A., 848 F. Supp. 2d 404, 407 (W.D.N.Y. 2012)). Form 18 had required only

(1) an allegation of jurisdiction; (2) a statement that the plaintiff owns the patent; (3) a statement that the defendant has been infringing the patent by making, selling, and using the device embodying the patent; (4) a statement that the plaintiff has given the defendant notice of its infringement; and (5) a demand for an injunction and damages.

Id.

On Dec. 1, 2015, however, Congress abrogated Rule 84 and the appended Form 18. Id. at *6. Chief Judge Geraci found that the abrogation of Rule 84 and Form 18 “erased any ambiguity” and was evidence that the higher bar of Twombly and Iqbal clearly applied to “all civil actions”—including direct patent infringement claims. Id. at *8 (internal citations, quotations omitted).

Under this standard, to successfully state a direct infringement claim, “a plaintiff must plead facts indicating that 'all the steps of [the] claimed method are performed by or attributable to a single entity.'” Id. at *9 (internal citations, quotations omitted). The court held that the plaintiff failed to satisfy this pleading standard because “[a]though plaintiff specifie[d] the relevant NYSDOT contract and allege[d] that defendant performed each step of the patent claim at issue, it [did] so using exactly—and entirely—its own patent language.” Id. The court reasoned:

To the extent plaintiff addresses every element, it is only by parroting the patent claim and prefacing it with an introductory attribution to the defendant. Under Twombly and Iqbal, plaintiff must do more than offer mere labels and conclusions. By describing defendant's conduct solely in the words of its own patent, plaintiff implicitly concludes that defendant's process necessarily meets every element of the patent claims—a legal determination, not a factual allegation.

Id. at *9-10 (Internal citations, quotations omitted).

In sum, the plaintiff's direct infringement claims failed because using the patent's language alone to describe the alleged infringing conduct amounts to a mere legal conclusion which is insufficient to meet the pleading standard set forth in Twombly and Iqbal.

Indirect Infringement Claim. Next, the court addressed whether the defendant was liable under a theory of induced infringement (which is an indirect infringement claim), and again, decided which pleading standard should apply. In contrast to direct infringement claims, there was no dispute that the pleading standard set forth in Twombly and Iqbal governed.

“For a claim of induced infringement to survive a motion to dismiss, the complaint must include facts that show there has been direct infringement, and second that the alleged infringer knowingly induced infringement and possessed specific intent to encourage another's infringement.” Id. at *11 (internal citations, quotations omitted). The plaintiff also asserted an alternative allegation of contributory infringement, which requires that the plaintiff show “1) that there is direct infringement, 2) that the accused infringer had knowledge of the patent, 3) that the component has no substantial noninfringing uses, and (4) that the component is a material part of the invention.” Id. at *12.

Both of these claims failed because they each require an adequate pleading of direct infringement and by “… simply referencing the description from its direct infringement claim, plaintiff's induced and contributory infringement claims suffer[ed] the same fate.” Id. Accordingly, the court recommended that the indirect infringement case be dismissed as well.

Other Developments in Patent Law

Around the same time as the Sessler decision, the Western District of New York heard another patent case with an interesting procedural history. In Steuben Foods v. Shibuya Hoppmann, No. 1:10-cv-00781-EAW-JJM, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 174347, at *12 (W.D.N.Y. Oct. 19, 2017), the defendants requested that the court grant their renewed motion to dismiss or transfer. Magistrate Judge Jeremiah J. McCarthy recommended that the defendants' renewed motion to dismiss or transfer due to improper venue be denied. However, soon after Judge McCarthy made this recommendation, the Federal Circuit decided a new case, In re: Micron Technology, 875 F.3d 1091 (Fed. Cir. 2007), prompting Judge McCarthy to vacate his own Report and Recommendation. See Text Order dated Nov. 16, 2017. (Dkt. #361). Judge McCarthy provided the parties an opportunity to submit supplemental briefs in light of the new Federal Circuit decision. See Report and Recommendation dated Jan. 16, 2018. (Dkt. #371).

Ultimately, Judge McCarthy found that the new decision did indeed undermine his original recommendation but that it nevertheless provided an alternative basis for denying the defendants' motion. Id. Consequently, in his Report and Recommendation dated Jan. 16, 2018, Judge McCarthy denied the defendants' motion and the parties have until Jan. 30, 2018 to object to his Report and Recommendation to the District Court. Although the court reached the same result, this case emphasizes the importance of staying current on the most recent case law while also exemplifying a unique situation where a judge vacated his own decision.

Sharon M. Porcellio, a member of Bond, Schoeneck & King, can be reached at [email protected]. Alyssa Jones, an associate at the firm, assisted with the preparation of this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

How Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Law Journal Column on Marital Residence Sales in Pending Divorces Puts 'Misplaced' Reliance on Two Cases

- 2A Message to the Community: Meeting the Moment in 2025

- 3Ex-Prosecutor Denies on Witness Stand That She Tried to Protect Ahmaud Arbery's Killers

- 4Latham's Lateral Hiring Picks Up Steam, With Firm Adding Simpson Practice Head, Private Equity GC

- 5Legal Restrictions Governing Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250