Putative Class Actions For Rent Overcharges

In their Landlord-Tenant column, Warren A. Estis and Michael E. Feinstein discuss 'Maddicks v. Big City Prop.,' a recent decision where the court found no basis for class certification.

February 06, 2018 at 02:00 PM

6 minute read

As practitioners in this area of the law are surely aware, there have in recent years been a spate of putative class action lawsuits commenced by residential tenants against their landlords, typically on behalf of both themselves and a proposed class of current and former tenants, claiming that their apartments were improperly deregulated and seeking rent overcharge damages. There are, however, certain standards that must be met in order for a court to “certify” a class under CPLR Article 9. In a recent decision of Justice Erika M. Edwards of Supreme Court, New York County in Maddicks v. Big City Prop., 2017 N.Y. Slip Op. 32385(U) (Sup. Ct. N.Y. County Nov. 16, 2017), the court, in dismissing the tenants' putative class action, explained the standards which must be complied with and found that in the case before it, the tenants had not satisfied them.

'Maddicks'

The facts as explained by the court in Maddicks were as follows. The plaintiffs were the tenants of apartments in 20 different buildings, each owned by different limited liability companies which were named as defendants. The class action complaint alleged that the buildings were part of a portfolio—the “Big City Portfolio”—managed by the same company. The complaint requested both declaratory and injunctive relief claiming that the subject apartments were improperly deregulated, and also sought damages for alleged rent overcharges. The proposed class included the current and former tenants of the 20 buildings owned by the various defendants.

The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint under CPLR 3211. They argued that the plaintiffs' attempt to bring the action as a class action failed as a matter of law because, among other reasons: (1) the defendants were all unrelated, separate entities and that the plaintiffs were improperly attempting to impute the alleged wrongful acts of one defendant against another without demonstrating how the entities are affiliated or legally intertwined; (2) the buildings had different property owners; and (3) the claims were improper for a class action because they were fact-specific and required individual case-specific analysis.

The court granted the motion and dismissed the complaint.

No Basis for Class Action Relief

The court observed that under First Department precedent, a motion to dismiss may be made prior to a motion to determine the propriety of the class under CPLR 902 “where it appears conclusively from the complaint and from the affidavits that there was as a matter of law no basis for the class action relief.”

The court further observed that it has “broad discretion” to determine whether the putative class meets the standards for class certification based on a review of the criteria set forth in CPLR 901(a). The court stated that under the statute, the prerequisites for class certification are “1) the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable; 2) there are questions of law or fact common to the class which predominate over any questions affecting only individual members; 3) the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the class; 4) the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class; and 5) a class action is superior to other available methods for the fair and efficient adjudication of the controversy.”

The court then went on to explain why the complaint did not satisfy the standards for class certification. First, the court found that “the questions of law or fact common to the class do not predominate over questions affecting only individual members.” In this regard, the court explained the plaintiffs “failed to properly assert how the defendants are factually or legally related or bound in this action” and that the allegations that all the properties were part of the “Big City Portfolio” was insufficient. The court further observed:

Here, plaintiffs attempt to join former and current tenants of several different properties, owned by separate and distinct companies, which are based on different theories of recovery, involving separate and distinct law and facts. Such claims are inappropriate for a class action.

The court also found that each of the plaintiffs' claims “requires fact-specific analysis which precludes class certification.” In so finding, the court observed that “[t]here are different buildings involved, different owners, different dates when the owners acquired the property, different prior owners, different registration periods and since there are different theories of recovery, each theory requires different defenses and evidence.” As such, the court concluded that:

Therefore, each theory of recovery or each owner may require different questions of law or fact which affect the individual members of the class associated with that owner and/or theory. Furthermore, since there are so many different entities and theories, each claim or defense may not be typical of the class which is necessary for class certification.

Finally, the court found that in the case before it, “a class action cannot be determined to be superior to other available methods for the fair and efficient adjudication of the controversy.” The court explained:

to proceed as a class, plaintiffs must waive their right to seek treble damages, since treble damages are penalties which are precluded in class actions, or exercise their right to opt out. Therefore, individual class members may wish to pursue administrative remedies under the Rent Stabilization Code in a Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR) proceeding or individual suit. Since the class representatives may not reflect the interests of the class based on the different theories a class action may not be the superior manner in which to bring plaintiffs' claims.

Conclusion

Justice Edwards' decision in Maddicks provides an excellent primer as to which types of rent overcharge matters may be appropriate for bringing as a class action, and certainly not all such matters will qualify. As the decision makes clear, the question of whether a matter will satisfy the above-described standards for class certification is a fact intensive analysis and will depend on the circumstances presented in each case.

Warren A. Estis is a founding member at Rosenberg & Estis. Michael E. Feinstein is a member at the firm.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

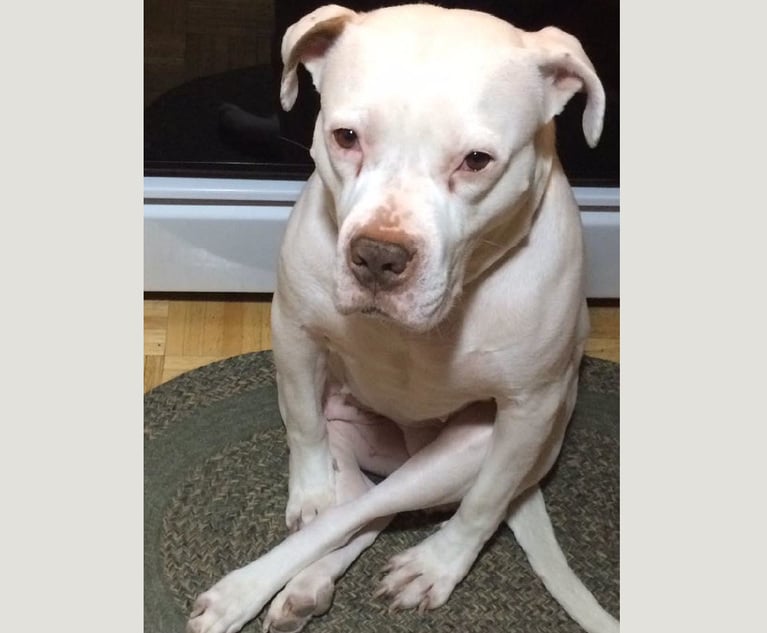

Decision of the Day: Court Rules on Judgment Motions Over Police Killing of Pet Dog While Executing Warrant

A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

13 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250