Stroock Sees Revenue Fall, Profits Leap as Strategic Review Sparks Big Changes

The firm de-equitized about 21 partners in 2017, creating a new multitiered partnership structure, and it tightened its practice focus after deciding it shouldn't strive to be "everything to everyone."

March 01, 2018 at 12:10 PM

7 minute read

It was a transformative 2017 for Stroock & Stroock & Lavan, a prominent New York firm that has faced sluggish revenue and profit growth since the financial crisis.

The firm de-equitized about 21 partners, creating a new multitiered partnership structure, and it spelled out its expectations for equity partners. It increased its leverage, tightened its focus on core practices and dove into pricing analytics, among other changes last year.

“We were a firm that hadn't really grown or innovated and wanted to be more energetic and on a higher performance track than we were,” said Jeffrey Keitelman, Stroock's co-managing partner. “We focused internally in 2017 to make this happen.”

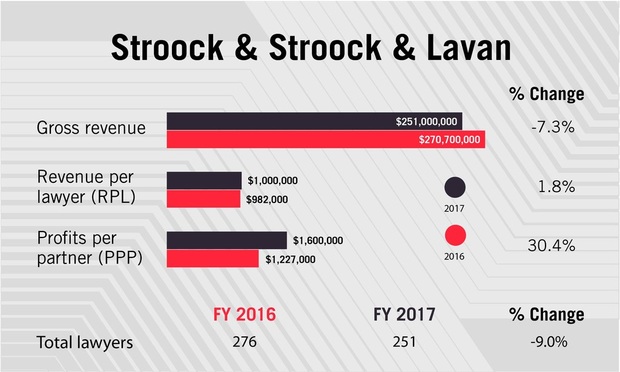

Amid all the changes last year and about 20 partner departures, gross revenue dropped 7.3 percent to $251 million in 2017. But revenue per lawyer increased about 2 percent to $1 million, and profit per equity partner shot up 30.4 percent to $1.6 million—the best performance Stroock has achieved in these two metrics in the last decade.

Keitelman said the results show that Stroock, ranked No. 116 in last year's Am Law 200 list of the highest-grossing U.S. firms, “punched well above its weight in 2017,” with its revenue per lawyer and profits per partner figures on par with much larger firms.

Keitelman said the results show that Stroock, ranked No. 116 in last year's Am Law 200 list of the highest-grossing U.S. firms, “punched well above its weight in 2017,” with its revenue per lawyer and profits per partner figures on par with much larger firms.

“On per capita metrics, we perform like an Am Law 50 firm; we just operate on a smaller scale,” he said in an email.

The changes came after a deep strategic review, in which the firm hired two consultant agencies, Clarity Group and Blaqwell. Afterward, Stroock's leadership developed a three-year plan, dubbed Stroock 2020, that would position the firm for success, Keitelman said. “We realized the law business has changed tremendously over the last decade,” he said, but “we hadn't changed that much.”

Keitelman, who joined Stroock in 2015 from DLA Piper, became co-managing partner in 2016, sharing the title with New York-based Alan Klinger. It was their mandate, along with other firm leaders, to execute the plan. “We needed to have a more coherent growth strategy,” Klinger said.

The firm decided to institute a formal non-equity tier “to take into account different expectations for different partners at different times in their career,” Keitelman said.

By the end of the first quarter of 2017, Stroock moved 21 equity partners to the newly created non-equity tier rank. Now, associates and counsel are generally required to go through the non-equity program before passing on to equity partnership, he said.

The non-equity tier includes younger attorneys and others who are given business development training, coaching and resources to eventually become an equity partner, as well as “special function” lawyers who have a particular knowledge or expertise but are not key business generators, Keitelman said.

The non-equity tier is also a place for senior lawyers who are toward the end of their legal career. Of the 21 who converted to non-equity ranks, 13 are senior status, Keitelman said.

“Over the years, the way the firm developed, it was a loose configuration of solo practitioners,” Keitelman said. “That's not the way we wanted it anymore. We wanted to be more collaborative and energetic. The non-equity partner program was one piece of that.”

The goal of the creating the non-equity tier wasn't to cut compensation and reduce expenses, said Keitelman and Klinger, noting the pay of the affected lawyers generally remained the same. “We want to give people the training and the support to be able to grow into a true owner of the business,” Klinger said.

In some ways, Stroock is catching up with the approach of other firms. Shearman & Sterling in 2016 expanded its non-equity partner ranks. While several Wall Street firms still don't have non-equity partners, some of the highest profitable firms across the county do, including Latham & Watkins; Kirkland & Ellis; Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher; and Weil, Gotshal & Manges.

Other Changes

In the last year, Stroock also created its first internal guidelines covering expectations for equity partners, and it introduced a performance evaluation and feedback system for partners.

The firm is placing more resources in its core areas: real estate, financial restructuring, corporate transactions and complex commercial litigation. “Once we made the decision to focus on some areas in our firm that were much more what we were known for, and not being everything to everyone, we became a much more focused firm,” Keitelman said.

While the firm still needs other expertise, such as in regulatory, tax and environmental, “we didn't pretend that they were going to be the main drivers of the firm,” Keitelman said.

The changes didn't stop there. In 2017, Stroock reorganized practice groups to generally focus more on industries and sectors; it implemented new technology; it expanding training for business development for partners and leaders; and it began emphasizing more lateral partner hiring.

Last year, Stroock also hired a specialist for pricing analytics and decided to cut down on contingency fee IP litigation, Klinger said. Now, Stroock is interested in partnering with litigation funders and using various alternative fee arrangements, Keitelman said.

Stroock also improved its leverage. “The firm historically has been very low leverage and partners needed to do a lot of the work,” he said. In some cases that mattered and in other cases, it wasn't required, he said.

Partner Moves

The changes were for not for everyone.

Last year, about a dozen Stroock lawyers moved to Proskauer, including Stuart Coleman, former co-managing partner and chair of its investment management practice. The departures also included corporate partners, as well as two intellectual property partners who went to King & Spalding.

Among the departures, “I would say about 90 percent of those were planned or expected as part of this strategic plan,” Keitelman said.

Meanwhile, the firm has hired in its strategic areas, including financial restructuring.

Keitelman said the adjustments have already produced results. While the smaller pool of equity partners played a big part in increasing partner profits 30.4 percent, Keitelman also credits the increases in productivity and leverage.

Keitelman said the 7.3 percent revenue drop in 2017 was anticipated because the firm had fewer attorneys billing hours. Total attorney head count dropped 9 percent to 251 lawyers.

So far this year, January and February have been “two of the best single months in many years” in revenue and billable hours, Keitelman said.

Stroock is open to mergers and acquisitions with other firms but is not in talks right now, he said. “There is no current plan, but like many other firms in the highly competitive area we are in, we are open to opportunities,” he said. “We don't need a merger at all, but we're not averse to talking about it.”

In 2017, Stroock lawyers landed high profile matters in all four of its core areas. That's especially true for its restructuring practice, which took roles in the Avaya and Seadrill bankruptcies. In the latter, Stroock is lead counsel to an ad hoc group of holders of unsecured bonds issued by Seadrill Limited and North Atlantic Drilling Ltd.

The firm's real estate team advised New York developer TF Cornerstone in a successful bid to create a 1.5 million-square-foot mixed-use destination, and Stroock is advising Pfizer on the sale of its current facility in Midtown and the simultaneous relocation of its headquarters.

Its litigation team helped secure a landmark ruling on behalf of victims of Iran-sponsored terrorism in Manhattan federal court. The firm also won a unanimous three-judge panel ruling at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit on behalf of American Express, obtaining approval of a $6.7 million class action settlement.

Stroock's corporate group is lead insurance M&A counsel to Atlas Merchant Capital, co-lead investor, in the $2.05 billion acquisition of Talcott Resolution, the run-off life insurance and annuity division of The Hartford. The deal has been reported as one of the largest insurance industry transactions of its kind.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Prosecutors Ask Judge to Question Charlie Javice Lawyer Over Alleged Conflict

Trending Stories

- 1The Intersection of Labor Law and Politics Following the Presidential Election

- 2Critical Mass With Law.com’s Amanda Bronstad: LA Judge Orders Edison to Preserve Wildfire Evidence, Is Kline & Specter Fight With Thomas Bosworth Finally Over?

- 3What Businesses Need to Know About Anticipated FTC Leadership Changes

- 4Federal Court Considers Blurry Lines Between Artist's Consultant and Business Manager

- 5US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250