NY's First Openly LGBTQ Presiding Justice 'Proud' of Distinction—but Not Defined by It

Justice Elizabeth Garry, a nine-year veteran of the Appellate Division, Third Department, who is known for her hard work, has more on her plate these days. Gov. Andrew Cuomo appointed her in January from among five candidates to serve as the sprawling 28-county's presiding justice, making her the first openly LGBTQ presiding justice in the state's history.

March 15, 2018 at 06:31 PM

8 minute read

Justice Elizabeth Garry often sees farmers on their tractors or lights blazing in barns as she is driving home late in the day from her courthouse in Albany to rural Chenango County. It makes her glad that she is a judge and not a farmer, she said.

“I may feel as if I have been working hard, but I know it is not that hard,” the farmer's daughter said.

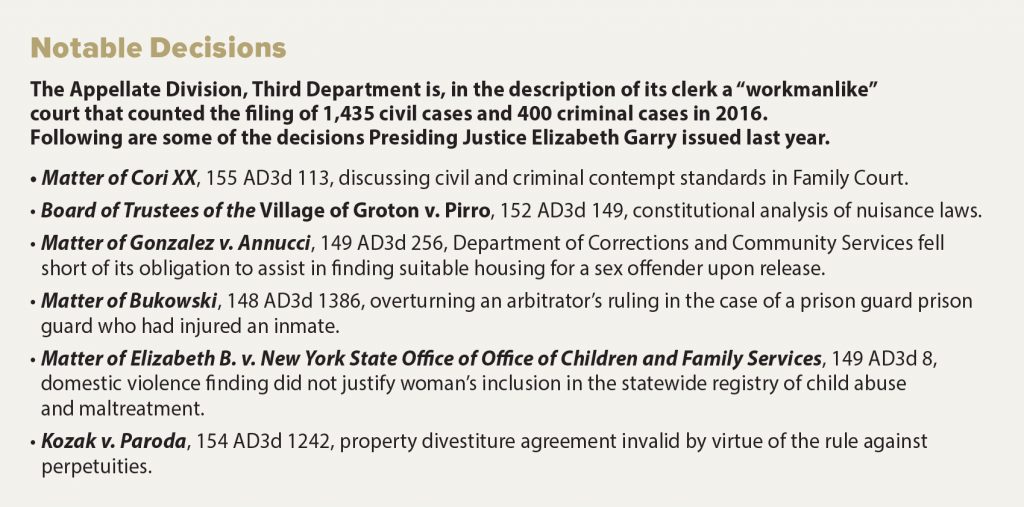

But Garry, 55, a nine-year veteran of the Appellate Division, Third Department, who is known for her hard work, has more on her plate these days. Gov. Andrew Cuomo appointed her in January from among five candidates to serve as the sprawling 28-county's presiding justice, making her the first openly LGBTQ presiding justice in the state's history.

Garry succeeds Karen Peters, who retired as the department's first female presiding justice. Peters called Garry's appointment “historic.”

Her appointment was made at the same time as that of Justice Alan Scheinkman in the Second Department. The state bar association welcomed both, but president Sharon Stern Gerstman said in a statement that she was “particularly pleased” that Garry's appointment was “yet another indication New Yorkers are equal under the law.”

Garry regards her new job as “a privilege and an honor.”

She said that her sexual orientation has nothing to with a judge's obligation to reach prompt, fair and appropriate decisions based on the law. But she added, “I am now quite proud to serve as a representative” of the once-excluded LGBTQ community.

Garry grew up with two brothers and a sister on a dairy farm with 50 milking cows and a total of 85 animals in the southwestern corner of Albany County, in one of the county's so-called “Hill Towns.” Garry said she was running heavy farm equipment by the time she was 12.

Her father, Harry Garry, was known as the “Singing Farmer” for his local performances. Her mother, Margery Smith was a country doctor. Both are deceased. Garry said that her parents gave her a very “powerful” work ethic, a sense of the rhythms of life, the ability to get along with people and a concern for the community.

“I am their living legacy,” she said.

After she graduated from Alfred University, where she studied religion and psychology, Garry cast about for several years for a career, taking a series of jobs that included a stint as a Christmas elf.

She was leaning toward insurance when she went to a party with a friend and watched fascinated as lawyers dissected issues by asking and answering questions, a technique that was new to her. She applied only to Albany Law School and graduated with honors in 1990.

Garry raised three children with her partner of more than 20 years to whom she is now married. She said that her sexual orientation never impeded her career, although she was sometimes “ostracized.” But she said that the treatment of LGTBQ people in general has improved in the few decades since she became a lawyer.

“I am part of that change,” she said.

Her first legal job was as a confidential law clerk for Justice Irad Ingraham, who is now retired, from 1990 to 1994. Ingraham recalls her marching into his office clutching a folder. She placed the folder on his desk, looked him in the eyes and declared, “I want this job.”

Garry got that job, but she was worried that it could create a scandal damaging to Ingraham if she had been outed early her career. There was no scandal. Ingraham said that he never talked to his clerk about her sexual orientation, and it wouldn't have made any difference.

Ingraham hired clerks for a year or two out of law school, but he came to admire Garry's legal talent, coupled with her attention to “the human element” of the law, so much that he eventually told her that she could stay as long as she wanted. She turned him down because she thought she needed trial experience as preparation for what had become her dream job: a judgeship.

Garry practiced for 12 years with the Joyce Law Firm in central New York. She also was elected to two terms as New Berlin Town justice and served on the planning board. She said her cases taught her the nuts and bolts of being a judge such as how to admit evidence. She also learned a lot from her clients.

“My years in private practice helped me tremendously,” she said.

Garry eventually walked into Ingraham's office carrying another folder, this one laying out how she expected to win the 2006 state Supreme Court race in the 10-county Sixth Judicial District. He tried to talk her out of it, arguing that as a Democrat she stood little chance in a district historically dominated by Republicans.

She refused to budge, and Ingraham endorsed her and campaigned with her even though he is a Republican and his stance angered the party. She won by almost 17,000 votes, a result that her mother credited in part to the farm vote.

“I didn't campaign waving the rainbow flag,” said Garry. “I did not campaign as the lesbian candidate—I campaigned as a highly qualified and hard-working candidate.”

Garry was thrilled but also upset in March 2007 when Gov. David Paterson, who was campaigning for more diversity on the courts, highlighted her family status in announcing he was appointing her to the Third Department. Garry sought to protect her mother from the description by persuading her mother's hometown newspaper not to include information about her same-sex relationship in its headline.

“I'm very open about who I am and anyone who knows me knows that,” she told another newspaper. “But I don't think that should be the focus of a judicial appointment.”

“I wanted to be a merit candidate,” she said in a November 2016 podcast discussing her appointment as co-chairman of the state courts' Richard C. Failla LGBTQ Commission, “I didn't want to be a diversity candidate.

“There was a part of me that didn't want the recognition for being a lesbian judge. I wanted to be a great judge.”

(Garry has stepped down as co-chairman of the commission because of her workload but remains a member).

However, she said that the importance of “claiming” her lesbian identity and representing LGBTQ people, in addition to doing “really great judge work,” has become clear to her. She said that at public appearances someone will almost invariably thank her for speaking up for them.

First Department Justice Marcy Kahn, the other co-chairman of the Failla commission, said that Garry was a “wonderful partner” who was full of enthusiasm and energy. She called Garry's appointment to the Third Department “absolutely groundbreaking” at this moment because it will help “normalize” the status of LGBTQ people in the courts. She said it sends a message that they must be integrated, along with everyone else.

Garry said she has always been treated well in the Third Department, which she said is composed of “some of the best judges I know.” Her mother, her partner and two of her children were present in 2009 when she was sworn in.

Robert Mayberger, clerk of the court, said that Garry's sexual orientation is more important to people on the outside than it is to people “on the inside of this building.” Garry is “universally respected,” bright and “incredibly capable,” he said. He added that she has used her time on the court to learn “everything one needs to know” about its operations.

Garry worked closely with Kathleen Campbell to establish the Del-Chen-O chapter of the League of Women Voters of the State of New York in 2016.

“She is thoughtful, reserved and maintains very professional relationships with those who appear before her,” said Campbell, who is the affiliate's president. “Her opinions are well-reasoned and she looks forward to work every day. She enjoys hearing cases and studying the law. She is a natural teacher and shares with others so they too will have opportunities to advance.”

Garry said that the court is running well, and she does not expect any drastic changes in its operations, only “tweaks.” One project just getting under way is the implementation of electronic filing. She also is pressing the governor's office to fill quickly two vacancies on her department's 12-judge complement.

She plans to shave the number of decisions that she writes, but expects to continue a heavy workload. She relishes the opportunity to help determine “big picture” policy issues as a member of the courts' administrative board.

“I'm thrilled to be here,” she said. “I'm going to do the best job of my life.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Elizabeth Cooper of Simpson Thacher on Building Teams in a 'Relationship Business'

4 minute read

For Paul Weiss, Progress Means 'Embracing the Uncomfortable Reality'

5 minute read

Ben Brafman's Professional Legacy After 50 Years? Himself

Many Americans Don't Trust the Supreme Court This Election; David Boies Isn't One of Them

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250