'Halo' and Willful Infringement Weaponizing Patent Owners

The increased risk of meaningful enhanced damages should ultimately reduce the incidence of willful infringement as potential defendants implement appropriate safeguards against copying or arrogantly ignoring the rights of patent owners. Achieving a proper balance, while not easy, should remain an important goal for our patent system.

March 23, 2018 at 03:00 PM

8 minute read

On a sunny February afternoon in San Jose, Calif., a jury of seven completed its deliberations and rendered its verdict in a patent dispute. The patentee prevailed, but the damage award was a relatively paltry $278,000—significantly less than what had been requested by the plaintiff. Microsoft v. Corel, No. 5:15-CV-05836-EJD, ECF No. 319 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 13, 2018).

On a sunny February afternoon in San Jose, Calif., a jury of seven completed its deliberations and rendered its verdict in a patent dispute. The patentee prevailed, but the damage award was a relatively paltry $278,000—significantly less than what had been requested by the plaintiff. Microsoft v. Corel, No. 5:15-CV-05836-EJD, ECF No. 319 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 13, 2018).

The jury, however, also ruled that the defendant's infringement was willful—a ruling that not only potentially trebles the award, but may trigger an exceptional case finding with a recovery of attorney fees. Id. If realized, payment from the defendant would soar into the multiple millions. Had the case been decided two years earlier, none of this would have occurred.

The Sport of Kings

Patent litigation, like horse racing, is an exclusive practice. Patent disputes have over the decades become one of the most rewarding forms of commercial litigation in the United States. Numerous jury verdicts in patent cases have landed hundreds of millions of dollars—several above $1 billion. The branded versus generic drug company wars, while without eye-popping verdicts, often implicate even more in terms of financial impact stemming from an injunction.

These clearly high-stake cases were interspersed with the growing presence of Non-Practicing Entities (NPEs)—patent pools, “trolls” and the like). These actions rarely involved large damage awards, but were characterized by multiple settlements for smaller amounts—settlements that however quickly grew to substantial sums.

Concurrent with these opportunities, the cost of patent litigation has kept pace. Governed by the Federal Circuit and its exclusive appellate jurisdiction, patent litigation typically follows a very expensive path through discovery, claim construction hearings, summary judgment motions—all now with expensive but nearly mandatory technical and financial experts. Parallel post-issuance proceedings within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) including Post Grant Reviews (PGRs), Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs), or Covered Business Method Reviews (CBMs) are very common and involve another added level of expense. The most recent AIPLA data estimates that patent litigation—through trial and appeal—averages $5 million per case. Am. Intellectual Prop. Law, AIPLA 2017 Report of the Economic Survey, I-122 (June 2017) (Average is $4,992,000. AIPLA categorization includes: Law Firms with 60 or more Attorneys, Litigation-Patent Infringement, All Varieties >$25M Inclusive of pre-trial, trial, post-trial, and appeal (when applicable)). This is truly the sport of kings.

Death Panels—The New Paradigm

During the last decade, various institutions in the United States became very disenchanted with the increasing damage awards and the role of litigation in monetizing patent assets. Both Congress and the courts stepped in and created a new series of barriers that eroded the value of patents in the market. While debated, the following three developments stand out:

The 2006 'eBay' Decision Restricting Injunctions. The Supreme Court ruled that injunctive relief was not a per se remedy in a patent case, removing the business ending threat of injunctions against many defendants. eBay v. MercExchange, 126 S. Ct. 1837, 1841 (2006). The removal of this risk substantially eroded the value of a patent.

The 2012 'Prometheus' and 2014 'Alice' Rulings and Patent Eligibility. The Supreme Court found that the PTO was being too generous in issuing patents and added new restrictive rules on what would be patent eligible. Alice Corp. Pty. v. CLS Bank Int'l, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014); Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2012). Many of the existing pool of patents in software and diagnostics—fast growing and sizable market sectors—were invalidated in a single stroke.

American Invents Act—Inter Partes Review of Patents. This new, elaborate, fast paced but expensive procedure permits defendants to seek review of an issued patent in the PTO under burdens and terms that are more favorable than available in district court litigation. The high rate of successful IPRs resulting in the loss of all patent rights was devastating to patent owners and their ability to monetize patents.

These policy and legal shifts undermined the value of patents as meaningful commercial assets.

The Resurrection of Willfulness

The recent activism by the Supreme Court on patents had a silver lining by resetting the law regarding willful infringement recited in In re Seagate Tech., 497 F.3d 1360, 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2007), abrogated by Halo Elecs. v. Pulse Elecs., 136 S. Ct. 1923 (2016). The 2007 Seagate decision by the Federal Circuit enforced a two-prong rigid test on whether a defendant's culpable conduct was willful under the patent statute. Statutory trebling of the damage award, under Seagate, required both prongs of objective and subjective willfulness proven by “clear and convincing” evidence of misconduct. This high hurdle was very difficult to meet, and often foreclosed even a presentation of a willful infringement claim to a jury even where the defendant had long standing knowledge of the patent. Bard Peripheral Vascular v. W.L. Gore & Assocs., 682 F.3d 1003, 1008 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

In 2016, the Supreme Court rejected this Seagate rule. In Halo, Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for a unanimous court, recognized the fundamental defect of the “objective” prong in the Seagate rule:

“Objective recklessness will not be found” at this first step if the accused infringer, during the infringement proceedings, “raise[s] a 'substantial question' as to the validity or non-infringement of the patent.” That categorical bar applies even if the defendant was unaware of the arguable defense when he acted.

Id. at 1930 (citation omitted).

In a departure from typical commercial litigations, patent infringement is a tort—an unlawful act against property rights that, as Congress intended, demands a strong response where the defendant's conduct is “egregious.” Id. at 1932. As noted by the Chief Justice, treble damages were more routinely awarded in the past, but always premised as a punitive response in the face of “aggravated circumstances.” Id. at 1928.

As the Halo court reasoned, egregious conduct forming the basis of enhanced damages can take many forms and the assessment examines the totality of circumstances regarding the defendant's intent. Id. at 1933. As recently expressed, willful infringement under Halo involves a defendant that acted despite a “risk of infringement that was either known or so obvious that it should have been known to the accused infringer.” Id. at 1930; see also WesternGeco v. ION Geophysical, 837 F.3d 1358, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Power Integrations v. Fairchild Semiconductor Int'l, Civil Action No. 04-1371-LPS, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 202298, *7 (D. Del. Dec. 8, 2017).

'I Know It When I See It'

While Halo recites a litany of adjectives such as “willful,” “wanton,” “reckless,” egregious” and perhaps the most colorful “like a pirate,” the new standard leaves significant discretion to the jury and ultimately the district court judge in setting out the punitive award. Post-Halo rulings, however, identify two core markers that can provide useful guidance.

Copying—Like a Pirate. Halo involved the review of two cases. The second case—Stryker v. Zimmer, is factually instructive; the defendant Zimmer “had all but instructed its design team to copy Stryker's products,” and had chosen a “high-risk/high-reward strategy of competing immediately and aggressively in the pulsed lavage market,” while “opting to worry about the legal consequences later.” Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1931. The jury found Zimmer's infringement willful and the district court trebled the $70 million jury verdict to more than $220 million. Id.

Zimmer's copying is a powerful example of the role evidence regarding copying will play in supporting a finding of willful infringement. Id.

Legal Opinion by Competent Patent Counsel. If copying is a sure-fire way to create a willful infringement problem, then seeking a timely “opinion of counsel” may be the ultimate insurance policy. Greatbatch Ltd. v. AVX, 2016 WL 7217625, at *3-4 (D. Del. Dec. 13, 2016).

In some ways, past is prologue as the matters of written opinions, privilege, discovery and waiver were all issues from the pre-Seagate era that led to the Seagate ruling. Because this pre-Seagate environment is now back, much of the case law from that era can and will play a role post-Halo.

The Role and Impact of 'Halo' and Willfulness

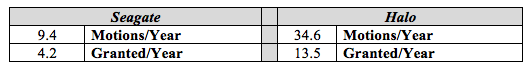

As one might expect, a clear trend is emerging regarding the treatment of willful infringement pre- and post-Halo. Isolating motion practice for the two periods of time is revealing. Comparing the Seagate era to the new Halo era, the data reflects a 368 percent increase in the number of motions resolved and a 323.9 percent increase in the rate motions were granted. (Data obtained from Docket Navigator on Feb. 28, 2018).

The bite of a patent is now stronger and the teeth include a more powerful financial sharpness, reversing the dulling effect of the past decade's long slide.

Conclusion

The debate regarding the role of willful infringement will continue. Uniformity in applying enhanced damages is important to establish the right incentives. To be sure, the increased risk of meaningful enhanced damages should ultimately reduce the incidence of willful infringement as potential defendants implement appropriate safeguards against copying or arrogantly ignoring the rights of patent owners. Achieving a proper balance, while not easy, should remain an important goal for our patent system.

James M. Bollinger is a partner at Troutman Sanders in New York.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250