Enforcing New York Convention Awards in the United States: Getting It Right

International Arbitration columnist John Fellas discusses the various distinctions made by the Second Circuit in 'Gusa' and their implications for parties applying to U.S. courts to reduce an award to judgment.

April 05, 2018 at 02:45 PM

11 minute read

John Fellas

John Fellas

In the course of its decision in GBF Industria de Gusa S/A v. AMCI Holdings, 850 F.3d 58 (2d Cir. 2017), cert. den., 138 S.Ct. 557 (2017), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit referred to the “confusion” that sometimes accompanies applications to U.S. district courts to reduce arbitration awards to judgment. It went on to provide the following guidance for the avoidance of such confusion in the future:

… we encourage litigants and district courts alike to take care to specify explicitly the type of arbitral award the district court is evaluating (domestic, nondomestic, or foreign), whether the district court is sitting in primary or secondary jurisdiction, and, accordingly, whether the action seeks confirmation of a domestic or nondomestic arbitral award under the district court's primary jurisdiction or enforcement of a foreign arbitral award under its secondary jurisdiction.

In this passage, the Second Circuit makes three sets of distinctions with respect to applications to U.S. courts to reduce arbitration awards to judgment, depending on: (1) the type of award that is the subject of the application (whether it is “foreign,” ”nondomestic,” or “domestic”); (2) the appropriate terminology in which the relief sought by that application should be expressed (whether, on the one hand, a court should be requested to “confirm” an award or, on the other, to “enforce” it); and (3) the juridical posture of the U.S. court considering that application (whether it is sitting as a court of “primary” or “secondary” jurisdiction). In making and explaining these various distinctions, it is interesting to note that the Second Circuit drew heavily from the draft Restatement of the Law (Third) The U.S. Law of International Commercial Arbitration (the Draft Restatement), a current project of the American Law Institute, the Chief Reporter of which is Prof. George A. Bermann of the Columbia Law School.

In this article, I discuss the various distinctions made by the Second Circuit in Gusa and their implications for parties applying to U.S. courts to reduce an award to judgment.

Let's begin with the type of award. According to the Second Circuit in Gusa, the three types of award it identifies are to be distinguished from each other by reference to two factors: (1) where the award was “made”; and (2) whether or not the award falls under the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the New York Convention). Before explaining these two factors, it might be helpful quickly to summarize the differences among the three types of award:[1]

• a foreign award is one that falls under the New York Convention and is made outside of the United States;

• a nondomestic award is one that falls under the Convention and is made in the United States; and

• a domestic award is one made in the United States, but does not fall under the Convention.

By speaking of where an award is made, the Second Circuit is referring to the legal seat of the arbitration, which is typically the place of arbitration specified in the parties' arbitration clause. As the court stated: “an arbitral award is 'made' in the country of the 'arbitral seat,' which is 'the jurisdiction designated by the parties or by an entity empowered to do so on their behalf to be the juridical home of the arbitration.'” Quoting Draft Restatement (§ 1-1 (s)).

The New York Convention, as most readers are surely aware, is an international treaty to which almost 160 countries (including the United States) are a party. It is implemented in U.S. law in Chapter 2 of the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). Article 1(1) of the Convention makes clear that it applies to both “foreign” and “nondomestic” awards, providing that it governs “the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards made in the territory of a State other than the State where the recognition and enforcement of such awards are sought [i.e., foreign awards]…[and] “to arbitral awards not considered as domestic awards in the State where their recognition and enforcement are sought [i.e., nondomestic awards].”[2]

A “foreign” award falls under the New York Convention by virtue of the fact that it is made in a Convention country other than the United States. For example, in Gusa, the award that was the subject of the U.S. action was a “foreign” award because it was made in another Convention country, France.

A “nondomestic” award is made in the United States, but falls under the New York Convention if it satisfies one of two conditions: (1) it was “made within the legal framework of another country, e.g., pronounced in accordance with foreign law[,]” Bergesen v. Joseph Muller, 710 F.2d 928, 932 (2d Cir. 1983); or (2) it was decided under U.S. law but involves either entities that are not U.S. citizens or, even if only U.S. citizens are involved, also involves “property located abroad, [or] envisages performance or enforcement abroad, or has some other reasonable relation with one or more foreign states.” 9 U.S.C. §202.

The second distinction posited by the Second Circuit relates to the terminology in which an application to reduce an award to judgment should be expressed. When it comes to a nondomestic award, the appropriate request is that the court confirm the award. When it comes to a foreign award, it is that the court recognize and enforce that award. The Second Circuit went on to explain that: “'Recognition' is the determination that an arbitral award is entitled to preclusive effect; 'Enforcement' is the reduction to a judgment of a foreign arbitral award … Recognition and enforcement occur together, as one process, under the New York Convention.”

The third distinction made by the Second Circuit relates to the juridical posture of the U.S. court. A U.S. court sits as one of primary jurisdiction in connection with Convention awards made in the United States, i.e., nondomestic awards. A U.S. court sits as one of secondary jurisdiction in connection with Convention awards made outside the United States, i.e., foreign awards. To put the point another way, a court of primary jurisdiction is in the same country as that of the arbitral seat (e.g., a U.S. court where the seat is New York), a court of secondary jurisdiction is in a different country to that of the seat (e.g., a U.S. court where the seat is Singapore).

There is an important difference between the authority of a court with respect to a Convention award depending on whether it is one of primary or secondary jurisdiction. While both primary and secondary jurisdiction courts have the authority to reduce an award to judgment—in the former case by “confirming” the award, in the latter by “enforcing” it—only a court of primary jurisdiction may set aside (or, in other terminology, vacate) that award.

This may require some explanation. When a court recognizes and enforces or confirms an arbitration award, it reduces that award to a U.S. judgment. As the Second Circuit noted in Gusa, “Under the New York Convention, [the] process of reducing a foreign arbitral award to a judgment is referred to as 'recognition and enforcement.' … Once a nondomestic arbitral award has been confirmed, it becomes a court judgment …” (emphasis added).

By contrast, when a court vacates an arbitration award, it holds, in essence, that that award has “no further force and effect.” Cf. United States v. Williams, 904 F.2d 7 (7th Cir. 1990). A court's decision as to whether, on the one hand, to confirm or enforce an award, and, on the other, to set aside an award is governed by different standards. The standards for confirmation (or enforcement) are governed by the New York Convention, Article V of which contains uniform standards applicable in all Convention countries. In the United States, for example, §207 of the FAA explicitly incorporates the standards of Article V of the Convention. However, the Convention contains no standards governing the set aside of awards. Rather, those standards are a matter of the domestic law at the arbitral seat. In the United States, §10 of the FAA contains the standards used by U.S. courts for assessing whether to vacate Convention awards rendered in the United States, which differ from the standards in Article V.

The essential point is that a secondary jurisdiction U.S. court has no authority to entertain an application to set aside an arbitration award under §10 of the FAA. Rather, it can consider only an application to enforce an award applying the very narrow standards in the New York Convention, which set strict limits on its authority. In Karaha Bodas Co. v. Perusahaan Pertambangan Minyak Dan Gas Bumi Negara, 364 F.3d 274 (5th Cir. 2004), the Fifth Circuit summarized the limited authority of a secondary jurisdiction court in this way: “a secondary jurisdiction court must enforce an arbitration award unless it finds one of the grounds for refusal or deferral of recognition or enforcement specified in the Convention. The court may not refuse to enforce an arbitral award solely on the ground that the arbitrator may have made a mistake of law or fact … . The party defending against enforcement of the arbitral award bears the burden of proof. Defenses to enforcement under the New York Convention are construed narrowly …” (citations and footnotes omitted).

By contrast, courts of primary jurisdiction may not only entertain an application to confirm a Convention award by reference to Article V, but also an application to set aside that award, using the domestic law standards set forth in §10 of the FAA. As the Fifth Circuit noted in Karaha Bodas: “While courts of a primary jurisdiction country may apply their own domestic law in evaluating a request to annul or set aside an arbitral award, courts in countries of secondary jurisdiction may refuse enforcement only on the grounds specified in Article V.”

A recent case from the S.D.N.Y. illustrates the impact of Gusa. BSH Hausgerate GMBH v. Jak Kamhi, 2018 WL 1136616 (March 2, S.D.N.Y.) concerned an application for the recognition and enforcement of award rendered in Switzerland, i.e., a foreign award. The award debtor sought to resist enforcement by arguing that the award was “ambiguous,” and it cited several cases “that mention ambiguity of an award as a reason for not confirming an award.” The S.D.N.Y. quickly disposed of that argument by noting that “[w]hen sitting in secondary jurisdiction, as the Second Circuit [in Gusa] has recently reminded district courts, the parameters within which a district court may refuse enforcement are rigidly circumscribed,” by the grounds set forth in Article V of the Convention. “The fact that Article V does not include ambiguity as an enumerated reason for this Court to refuse enforcement is Respondent's Achilles' heel, because it is not clear that ambiguity as argued is an appropriate ground to refuse enforcement … .” The court distinguished some of the cases cited by the award debtor in support of its “ambiguity” argument precisely on the ground that they were relied upon by courts sitting in primary jurisdiction and thus went beyond the grounds the court was permitted to consider under Article V: “Some cases Respondent cites are in the context of courts sitting in primary jurisdiction, which, as already noted, permits a wider range of available adjudicative options.”

Parties applying to reduce a New York Convention award to judgment would do well to follow the guidance and terminology used by the Second Circuit in Gusa, and take care that the court decisions they cite in support of their positions correspond in juridical posture to that of the court deciding the application.

Endnotes:

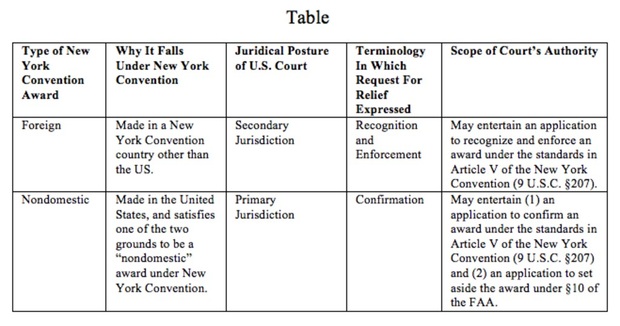

[1] This article is focused on New York Convention awards, and thus domestic awards are beyond its scope. I have set out the various distinctions relating to foreign and nondomestic awards made by the Second Circuit in Gusa in the Table.

[2] While the Second Circuit did not directly address this point, the same terminology of “foreign” and “nondomestic” would logically apply to awards falling under the Inter-American Convention on International Commercial Arbitration (often called the “Panama Convention”), which is implemented in U.S. law in Chapter 3 of the FAA.

John Fellas is a partner at Hughes Hubbard & Reed.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Unraveling of Sean Combs: How Legislation from the #MeToo Movement Brought Diddy Down

When It Comes to Local Law 97 Compliance, You’ve Gotta Have (Good) Faith

8 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1In Novel Oil and Gas Feud, 5th Circuit Gives Choice of Arbitration Venue

- 2Jury Seated in Glynn County Trial of Ex-Prosecutor Accused of Shielding Ahmaud Arbery's Killers

- 3Ex-Archegos CFO Gets 8-Year Prison Sentence for Fraud Scheme

- 4Judges Split Over Whether Indigent Prisoners Bringing Suit Must Each Pay Filing Fee

- 5Law Firms Report Wide Growth, Successful Billing Rate Increases and Less Merger Interest

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250