Book Review: Lessons From the Chinese Exclusion Act

As the book reminds us, Chinese exclusion was hurtful, harmful, ineffective, misguided and shortsighted.

April 09, 2018 at 03:46 PM

6 minute read

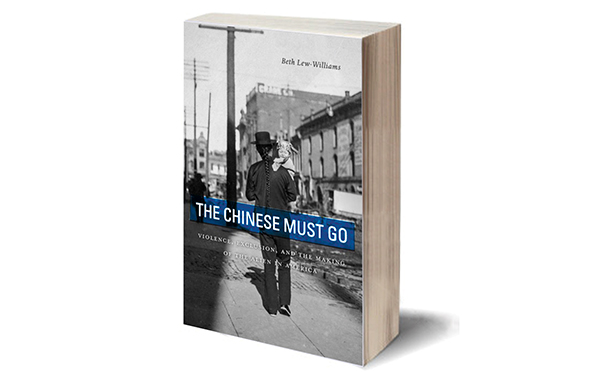

The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America

The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America

By Beth Lew-Williams

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 360 pages, $39.95

As the 1880s dawned, the U.S. economy was mired in a deep economic recession triggered by the Panic of 1873. Unemployment was high, and wages were depressed. On the West Coast, the presence of 100,000 Chinese immigrant laborers was perceived as a threat to the white working class, whose rhetoric and violence pressured politicians to act. In her new book, Beth Lew-Williams masterfully recounts the nativist upheaval that produced the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the first American law to single out an immigrant group for exclusion. The law spawned a regrettable national origins approach to U.S. immigration, which lasted until 1965. The book contains useful lessons for our own time, as the immigration reform debate continues.

At a time of open U.S. borders, Chinese immigrants first arrived on the West Coast in the early 1850s. Industrialists took a liking to them because they tended to be dependable and work for modest wages. Over the next thirty years, Chinese labor helped build the railroad, mining, lumber, fishing, and agricultural businesses of the American West.

As the 1870s drew to a close, however, anti-Chinese sentiment on the West Coast proliferated, spurred by labor organizations and demagogues such as Denis Kearney, whose strident polemics (“the Chinese must go”) encouraged whites to target both the Chinese and political leaders who refused to act. At a time when non-Hispanic whites made up approximately 90% of the U.S. population, this “concerted intolerance” turned the Chinese question into a national issue.

The book is organized into three parts. Entitled “Restriction,” Part I “traces the contested politics and geopolitics” that gave rise to the 1882 Act, and then “considers how uneasy compromises at the national level affected immigration enforcement at the local level.”

Part I's strength is its description of the American political landscape of the 1880s. While white laborers and many newspaper publishers and politicians in the West were anti-Chinese, most in the rest of the country were not. Industrialists and politicians in other parts of the U.S. disfavored excluding the Chinese, because their labor was valued and it was feared that heavy-handed measures would tarnish American prestige abroad and anger the Chinese government, which could retaliate by restricting American access to Chinese markets.

The 1882 Act barred Chinese laborers for ten years and allowed entry to only certain exempt classes, such as students, teachers, travelers, merchants and diplomats. For the first time, a U.S. law barred a foreign people from becoming naturalized citizens, making them permanent aliens.

As recounted by the author, the 1882 Act caused strains with the Chinese government, because it abrogated the Burlingame Treaty (1868), in which the U.S. agreed that “Chinese subjects in the United States shall enjoy the liberty of conscience and shall be exempt from all disability or persecution[.]” In Chae Chin Ping v. U.S. (1889), the Supreme Court upheld the federal government's power to exclude foreigners and pass legislation that contradicted prior treaties.

The book also explains well how weaknesses in the 1882 Act frustrated its purpose. The exempt classes proved easy to exploit, and Congress' refusal to adopt or fund enforcement measures undermined the law.

As chronicled in Part II, entitled “Violence,” the ineffectiveness of the 1882 Act soon became evident and produced an epidemic of anti-Chinese violence across the West. This is the most impressive part of the book, utilizing a broad array of sources, including many national and local archives. The narrative is enhanced with personal accounts of the violence and hardship suffered by individual Chinese laborers and merchants, particularly from the expulsions that took place in Seattle and Tacoma.

Entitled “Exclusion,” Part III “explains how local racial violence became an international crisis and spurred a new federal immigration policy.” The Chinese exclusion question also became a common theme in presidential year election politics, as both parties tried to woo Western voters with tough immigration stances against the Chinese.

For example, in the Scott Act (1888), Congress extended the 1882 law and barred most Chinese laborers who had returned to China from re-entering the U.S. In the Geary Act (1892), Congress again extended the Chinese exclusion and, over the objection of the Chinese government, began requiring all Chinese in the U.S. to register with the federal government and obtain certificates of residence, the precursor of the green card. Finally, the Johnson-Reed Act (1924) excluded all classes of Chinese immigrants and other Asian groups. The 1924 Act also limited immigration from eastern and southern Europe, as nativists sought to preserve the racial dominance of non-Hispanic whites, which continued to constitute at least 85% of the U.S. population until the early 1960s.

Despite these obstacles, Chinese immigrants continued to flow into the U.S. Between 1882 and 1943 (when the Magnuson Act overturned the exclusion and allowed Chinese to become naturalized citizens), 300,000 Chinese came to the U.S. The author observes that, during that 60-year period, the Chinese constituted the first wave of so-called “illegal immigrants” and were the subjects of extensive commercial human smuggling.

Large-scale Chinese immigration did not occur until the passage of the Hart-Celler Act of 1965, which abolished the national origins system and replaced it with preference visa categories that focused on an immigrant's skills and family relationships with U.S. citizens. The 1965 Act also brought U.S. immigration policy into line with other anti-discrimination measures, such as the Civil Rights Act (1964) and Voting Rights Act (1965). America finally became the open nation it had always claimed to be.

As the book reminds us, Chinese exclusion was hurtful, harmful, ineffective, misguided and shortsighted. Since 1965, the U.S. has become a more diverse, less white, better educated and stronger nation. As one measure of excellence, the George Mason University Institute for Immigration Research reported in 2016 that: (a) 40% of the Nobel Prizes have been awarded to Americans; (b) 35% of that 40% were awarded to American immigrants; and (c) most of that 35% come from diverse faculty pools at the elite U.S. universities. Like other immigrant groups, the Chinese have greatly contributed to this excellence.

Jeffrey M. Winn is a management liability attorney with the Chubb Group, a global insurer, and a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'We Learn Much From the Court's Mistakes': Law Journal Review of 'The Worst Supreme Court Decisions, Ever!'

6 minute read

'Midnight in Moscow': A Memoir From the Front Lines of Russia's War Against the West

9 minute read

'There Are Heroes in Every Story': Review of 'The Eight: The Lemmon Slave Case and the Fight for Freedom'

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Inside Track: Why Relentless Self-Promoters Need Not Apply for GC Posts

- 2Fresh lawsuit hits Oregon city at the heart of Supreme Court ruling on homeless encampments

- 3Ex-Kline & Specter Associate Drops Lawsuit Against the Firm

- 4Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

- 5The Importance of Federal Rule of Evidence 502 and Its Impact on Privilege

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250