As Cohen and Prosecutors Wrestle, Lawyers Differ on Raid's Ripple Effect on Privilege

The fundamental importance of the attorney-client privilege itself is coming intensely into focus for the general public.

April 16, 2018 at 12:45 PM

9 minute read

Attorneys for President Donald Trump's personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, say that his work-related files, seized by the FBI last week in a raid aimed at finding evidence of crimes committed by the lawyer, contain thousands of attorney-client privileged documents and communications tied to “numerous clients.”

Manhattan federal prosecutors maintain that is not true. “Cohen has exceedingly few clients and a low volume of potentially privileged communications,” they say.

And at a court hearing on April 13, U.S. District Judge Kimba Wood of the Southern District of New York, tasked with properly protecting those covered by the privilege while also allowing prosecutors to investigate Cohen, gave the president's lawyer until Monday to produce a list of his claimed “numerous clients,” along with evidence of his relationships with them. The judge seemed dubious of Cohen's assertions about the clients and said that, without proof, she is “likely to discount the argument that there are thousands if not millions” of privileged communications strewn throughout his files.

As the early stages of one of the most high-profile criminal investigations in decades unfold—the probe into possible white-collar crimes by Trump's personal lawyer—the fundamental importance of the attorney-client privilege itself is coming intensely into focus for the general public.

The privilege sits at the core of a key early battle between the government and Cohen's team: the determination of exactly what communications and documents the government may get to consider as possible evidence of criminality in a case that could ultimately affect the course of a presidency. Specifically, the two sides are fighting over an injunction and temporary restraining order proposed by Cohen—and being considered by Wood at a court hearing Monday afternoon—that could decide who gets early control over reviewing the materials for attorney-client privileged communications.

At the same time, the highly publicized fight over both the materials' review and the initial raid of Cohen's home, office and hotel room has caused concern among some lawyers that public confidence in the privilege will wind up becoming a casualty of the forces at play, as Trump's lawyer is put in the crosshairs.

While these concerned lawyers concede that they, like the public, have not been privy to the sealed allegations of “probable cause” underpinning the search warrant obtained by prosecutors who wanted the raid, they wonder openly whether Robert Khuzami, the Southern District of New York's deputy U.S. attorney, and his team have exercised the type of restraint called for before infiltrating a lawyer's office.

The maneuver itself, they say, is beyond the norm and rarely undertaken, precisely because the legal system, as a whole, functions best when people faithfully believe that what they tell their lawyers will never be revealed.

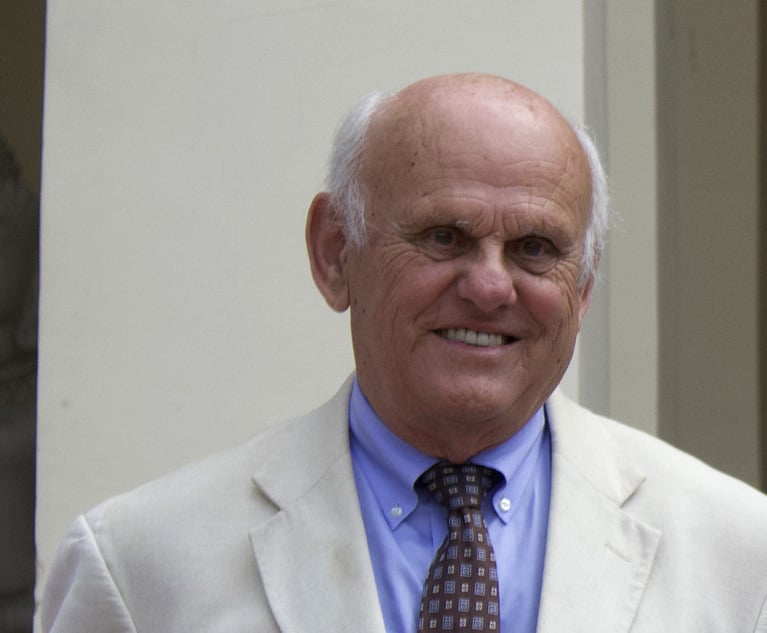

“I think most of the time, prosecutors are saying that doing this [type of raid] would undermine the whole system, and that it is more important that people feel that they have lawyers they can speak to” confidentially, said Raoul Felder, a nationally recognized New York-based divorce and family lawyer who has been critical of the prosecutors' decision to seize files from Cohen.

Usually, prosecutors “use their discretion well and don't do it, but apparently not this time,” said Felder, who was a Brooklyn federal prosecutor in the 1960s, dryly.

Moreover, he said, if prosecutors cannot obtain from other sources the evidence they want on a lawyer who has potentially committed crimes, then they should stop there and go no further.

“The aura is so bad,” he continued, “as far as the effect on the general public [in confidence that their communications will be kept private], that you do it only in the most serious cases.” He added that to conduct the raid amounts to “disturbing a legal profession that works, that operates with the privilege—that operates to the people's advantage.”

“This is like you throw a pebble in a lake, and then it goes all the way out,” he went on, regarding the raid's potential effect on clients, adding that prosecutors “have to think how far the ripples go.”

But Khuzami and his team, which includes Assistant U.S. Attorneys Thomas McKay, Rachel Maimin and Nicolas Roos, made clear on April 13 that, for one, they don't believe there are many attorney-client privileged materials lurking in Cohen's files. In court papers April 13, they wrote that searches they're conducting “are the result of a months-long investigation into Cohen, and seek evidence of crimes, many of which have nothing to do with his work as an attorney, but rather relate to Cohen's own business dealings.”

In addition, the team argued that, according to a witness, Cohen may have just one client: Trump. They also spelled out that they'd already secretly obtained judicial search warrants for email accounts maintained by Cohen, as part of an ongoing grand jury investigation, and that a review of Cohen emails indicated there were zero emails exchanged between him and the president.

Finally, and pointedly, the prosecutors argued that they had a right to obtain the warrant and collect the materials by force and surprise because they had reason to believe that Cohen's office held evidence of crimes that “sound in fraud and evidence a lack of truthfulness,” and that “absent a search warrant, these records could have been deleted” by Cohen.

Still, according to Harvard Law School professor and trial lawyer Alan Dershowitz—who, like Felder, has been outspoken in recent days against the government's raid of Cohen's files—such arguments put forward by the Southern District prosecutors hold little water and should not be used to justify raiding Cohen or any other lawyer.

In Dershowitz's view, the issue of potential infringement of a client's privileged information, and the effect of undermining clients' confidence in the privilege and their rights, remained.

“Nothing has been altered by what came out today,” he said in phone interview April 13 after news reports had been published describing the temporary restraining order hearing before Wood and certain briefing arguments made by each side.

Then he reiterated his concern that, pursuant to the government's proposed use of a government-agent “filter” or “taint” team to review the materials collected for privileged communications, “government agents will get to read material that potentially may belong to [Cohen's] clients” according to the rules of the privilege.

“All you need is one line” of privileged information to be present, he said, for a damaging violation to occur and, in this case, to perhaps be widely publicized.

But Mark Zauderer, a senior partner at the Manhattan litigation boutique of Flemming Zulack Williamson Zauderer, pointed out in a separate interview last week that “the fact that, as reported, there was a search warrant of the lawyer's offices suggests that the evidence presented by the government [to a magistrate judge] in support of the search warrant showing probable cause, was likely strong, if for no other reason, that both prosecutors and judges in this circumstance, understandably, proceed conservatively,” given that Cohen represents the president.

Then, on April 13, after more was learned about both the government's assertions and its previously secured warrants regarding Cohen's emails, Zauderer said that he believed the government's position appeared even stronger.

“Lurking in the defendants' arguments was always the notion that this is an unusual situation, because it involved a lawyer with a client who is the president of the United States” and therefore the president's confidences may be leaked or revealed, Zauderer said.

“But what the government is now saying is that this is really a rather conventional investigation of Cohen,” he continued, “and that its present warrant that permitted a search was merely a follow-up warrant on other warrants that apparently uncovered evidence of possible criminal behavior” by Cohen.

“Given the fact that Cohen apparently does not have a lot of clients—he may not have had more than one client—it may well be the simple focus here is Cohen's business activities, [and] it looks like Cohen's argument that there should be some special treatment that should be accorded in the privilege review—it looks like that argument seems to have unsteady legs.”

At the same time, Zauderer also believed that, “taking the long view,” any damage to the public's faith in using the attorney-client privilege would dissipate.

“A raid on a lawyer's office like this, which generates great publicity, one could speculate could chill communications between clients and their lawyers,” he said. But “since these kinds of search warrants of lawyers are not common and are usually not highly publicized, it is quite possible that, as far as public perception is concerned, that this incident will, over time, fade into the background.

“And it is likely that, as the facts become better known in this case, it will not prove to be the routine situation, and that search warrants of lawyers' offices will continue to be unusual.”

Felder, though, still viewed differently the potential for damage to perhaps the oldest and most sacrosanct of privileges in the law.

“Every case is unusual,” he said, “and now for the next hundred years, there will be this case, and there is always some special reason prosecutors are going to find to [seize materials from a lawyer]. There will be a missing child, for instance, so they'll say we need to open the attorney-client files. There will always be a reason.

“Doing this is opening Pandora's box,” Felder said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Bankruptcy Judge Clears Path for Recovery in High-Profile Crypto Failure

3 minute read

US Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Brought Under NYC Gender Violence Law, Ruling Claims Barred Under State Measure

In Resolved Lawsuit, Jim Walden Alleged 'Retaliatory' Silencing by X of His Personal Social Media Account

'Where Were the Lawyers?' Judge Blocks Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 2Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 3Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 4Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

- 5Freshfields Hires Ex-SEC Corporate Finance Director in Silicon Valley

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250