Decision Tackles Privilege Issues When Third-Party Consultant Is Involved

In her Western District Roundup, Sharon M. Porcellio discusses a recent decision in which Judge Payson tackled a seemingly routine situation that results in a complex question: What happens to attorney-client privilege when there is a third-party consultant involved in the communications?

April 26, 2018 at 02:45 PM

8 minute read

Since our last update, U.S. Magistrate Judge Marian W. Payson examined the topical issue of attorney-client privilege. In doing so, Judge Payson provided a detailed analysis of theories and exceptions necessary to determine whether certain communications constitute attorney-client communications protected from disclosure, including the agency exception and functional equivalent doctrine. Most notably for practitioners, both in-house and outside counsel, Judge Payson tackled a seemingly routine situation that results in a complex question: What happens to attorney-client privilege when there is a third-party consultant involved in the communications?

Introduction

In Narayanan v. Sutherland Global Holdings, No. 15-CV-6165T, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12358, at *1 (W.D.N.Y. Jan. 25, 2018), plaintiff filed a motion to compel defendant, Sutherland Global Holdings, to produce documents as to which Sutherland asserted attorney-client privilege.

By way of background, plaintiff was a former employee of Sutherland asserting breach of contract and unjust enrichment claims against Sutherland. In response, Sutherland asserted a set-off defense and a counterclaim relating to an allegedly faulty land transaction in India (the land acquisition). Prior to commencement of the suit, Sutherland hired Freed Maxick CPAs, P.C., a consulting accounting firm, to investigate the Land Acquisition.

In its engagement letter with Sutherland, Freed Maxick agreed to create a report, which “was expected to detail, among other things, its findings related to the … Land Acquisition and its assessment of internal controls at Sutherland and to provide recommendations for improvements to internal controls at Sutherland.” Id. at *5. Sutherland also hired an Indian-based law firm, Rank Associates, to provide legal advice about the Land Acquisition and to advise on how to best recoup the money lost in the Land Acquisition.

Plaintiff sought unredacted preliminary and final versions of the report, which also contained legal advice from Rank. In addition, plaintiff sought emails and documents between and among Rank, Sutherland, and Michael Russo, a certified public accountant and managing director of Freed Maxick.

Plaintiff's primary argument was that Freed Maxick's involvement in communications between Rank and Sutherland waived the attorney-client privilege. He also contended that Sutherland waived any privilege attaching to the communications by placing the advice provided by Rank at issue in the litigation.

In opposition, Sutherland argued that the attorney-client privilege remained intact because “Russo was an agent of Sutherland whose involvement was 'necessary and indispensable' to facilitate the attorney-client communications between Rank and Sutherland, or, alternatively, because Russo was the 'functional equivalent' of a Sutherland employee.” Sutherland also maintained that it had not placed the communications at issue in this litigation.

The court did not reach the latter issue because Judge Payson found that the communications at issue were either not privileged communications or were not protected by the attorney-client privilege if the privilege had attached.

The Agency Exception

The attorney-client privilege is a rule that keeps communications between attorneys and clients confidential. Disclosure of those communications to persons outside that attorney-client relationship, however, waives the attorney-client privilege. One exception to this general rule is called the agency exception, “where communications are made to counsel through a hired interpreter, or one serving as an agent of either attorney or client to facilitate communication.” Id. at *11 (quoting Allied Irish Banks v. Bank of America, N.A., 240 F.R.D. 96, 103 (S.D.N.Y. 2007)). “The party asserting the agency exception must show: (1) a reasonable expectation of confidentiality under the circumstances, and (2) that disclosure to the third party was necessary for the client to obtain informed legal advice.” Id. at *11-12 (quoting Homeward Residential v. Sand Canyon, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 171685, at *5 (quotation marks omitted)).

At the outset, the court noted that Freed Maxick was not Rank's client and that accordingly, any communications with Freed Maxick that disclosed attorney-client advice waived the privilege unless they fell within this or another exception. With regard to confidentiality, Judge Payson found that Sutherland had “adequately demonstrated” its 'subjective belief' that Russo and his team would keep the communications with Rank confidential. The court had doubts, however, concerning whether the communications that were disclosed to the third party were necessary for the client to obtain informed legal advice.

The court then analyzed four categories of documents under the agency exception, holding this exception inapplicable to each category.

Communications between Rank and Russo: Russo claimed that his disclosures and explanations to Rank were necessary to “guide” Rank's legal advice to Sutherland. More specifically, Sutherland claimed that “Russo provided Rank with the facts necessary for Rank to provide legal advice to Sutherland.” The court did not find this argument compelling. In explaining its reasoning, the court relied upon a Second Circuit case, United States v. Ackert, 169 F.3d 136, 138 (2d Cir. 1999). Judge Payson explained that “'a communication between an attorney and a third party does not become shielded by the attorney-client privilege solely because the communication proves important to the attorney's ability to represent the client.'” Narayanan, No. 15-CV-6165T, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12358, at *16 quoting Ackert, 169 F.3d at 139.

Russo maintained that his investigation, which he conducted without involvement by Sutherland employees, provided necessary facts to Rank that Sutherland otherwise could not. The court found that although it was potentially helpful for Rank to speak to Russo, Rank did not need Russo to interpret the information for it. Thus, the communications were not privileged.

Exchanges from Rank to Russo and Sutherland. The court found the statements advanced to support this argument conclusory. There was no factual showing that either Sutherland or Rank required Russo to facilitate Rank's legal advice. Accordingly, “the decision to include Rank's legal advice in the Report was one of convenience, rather than necessity.” This alone would not shield the privilege from waiver.

Sutherland to Rank and Russo. K.S. Kumar, Chief Commercial Officer of Sutherland in India, sent an email to both Rank and Russo. The court held that Sutherland failed to show that this communication was privileged. The court reasoned that “Vellodi's [CEO of Sutherland] declaration addresses only his conferral with Russo, and not the necessity of Russo's involvement in communications from Kumar to Rank” and that “Russo's declaration only addresse[d] his communications with Rank and d[id] not reference his involvement in communications between Kumar and Rank several months after the issuance of the Report.” Id. at *19-20. This communication is, thus, not privileged.

Russo to Himself. Sutherland also asserted that a spreadsheet which Russo emailed to himself was privileged. The court held that this spreadsheet was not privileged both because the record did not demonstrate that Rank was a party to the communication and because the record did not demonstrate that the spreadsheet reflected privileged information. The court also pointed out that it was unclear as to how a spreadsheet of this nature could even potentially reflect privileged information.

In summary, Sutherland had not met its burden of showing that the information at issue was privileged under the agency exception.

The Functional Equivalent Doctrine

Sutherland alternatively argued that attorney-client communications shared with Russo were privileged because Russo was the “functional equivalent” of a Sutherland employee. Although noting that the Second Circuit has never recognized the “functional equivalent” doctrine, Judge Payson stated:

[i]n determining whether a third-party consultant should be considered the functional equivalent of a company's employee, courts evaluate: whether the consultant had primary responsibility for a key corporate job, whether there was a continuous and close working relationship between the consultant and the company's principals on matters critical to the company's position in litigation, and whether the consultant is likely to possess information possessed by no one else at the company.

Id. at *21 (quoting Exp.-Imp. Bank of the United States v. Asia Pulp & Paper Co., Ltd., 232 F.R.D. 103, 113 (S.D.N.Y. 2005)).

After a detailed analysis, the court decided that Russo was not a functional employee of Sutherland. It cited many reasons for its decision including the fact that Sutherland retained the authority to make decisions on issues for which Freed Maxick was consulted. The court also stated that Sutherland was unable to demonstrate that there was a continuous and close working relationship between its principals and Russo's team on matters critical to Sutherland's position in anticipated litigation at the time of the communications. Furthermore, the fact that Russo knew information about the Sutherland Land Acquisition that no one else at Sutherland knew, did not transform Russo into a Sutherland employee.

Conclusion

This case sheds light upon the potential complexity of attorney-client privilege issues concerning third party consultants. In the end, the court held that none of the documents/communications at issue were privileged, dismissing the applicability of both the agency exception and the functional equivalent doctrine, and providing for full disclosure.

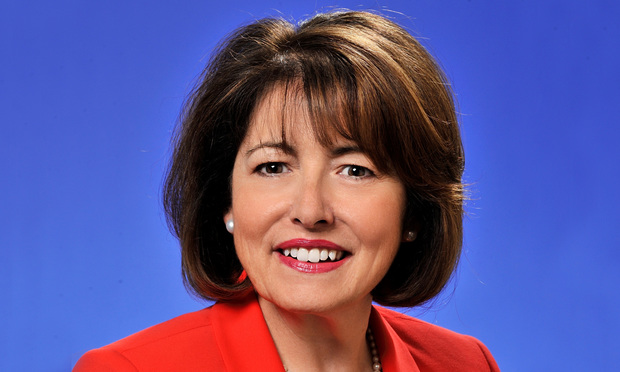

Sharon M. Porcellio is a member of Bond, Schoeneck & King, representing businesses and institutions in commercial litigation and employment matters. She can be reached at [email protected]. Alyssa Jones, an associate with the firm, assisted with the preparation of this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Unraveling of Sean Combs: How Legislation from the #MeToo Movement Brought Diddy Down

When It Comes to Local Law 97 Compliance, You’ve Gotta Have (Good) Faith

8 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Parties’ Reservation of Rights Defeats Attempt to Enforce Settlement in Principle

- 2ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 3States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 4Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 5Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250