Protecting Our Country From Momentary Passions

The bulwark of a strong and independent judiciary is necessary to protect our country against such momentary passions—compelling though they may be—for if we fail in that, we lose our very foundation.

April 30, 2018 at 03:10 PM

7 minute read

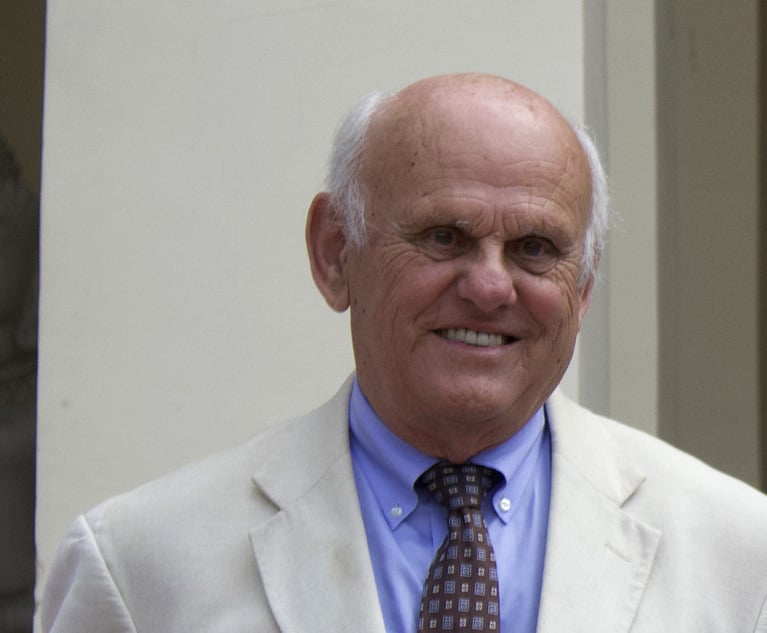

Gerald J. Whalen, Presiding Justice, Appellate Division, Fourth Department

Gerald J. Whalen, Presiding Justice, Appellate Division, Fourth Department

In a 1937 speech to the New York State Bar Association, then-Assistant Attorney General Robert H. Jackson offered a stark view of the Supreme Court's role in government. He posited that the judicial branch, with its “[u]nreasoning devotion to precedent” in ignorance of the realities of life, had created a “[g]overnment by litigation” in contravention of effective policy enforcement. Robert H. Jackson, Address Before the New York State Bar Association (New York, N.Y., Jan. 29, 1937). “Congress looks forward to results, the courts look backward to precedents, the President sees wrongs and remedies, the Courts look for limitations and express powers. The pattern requires the Court to go forward by looking backward.” Id. Jackson's specific target that night was the monopolizing of the Court by the legal profession, with its penchant for technical legal patterns only attorneys can unravel. Jackson found that the conflict in philosophy between this staid legal thinking and expeditious political progress created a “struggle between every progressive administration in our history against the Federal bench.” Id.

Jackson's rebuke that night of the “paralyzing complexity of government” (id.) unintentionally foreshadowed Franklin D. Roosevelt's attempt to change the personality, if not the functionality, of the court to an institution more supportive of his goals. Robert H. Jackson, That Man: An Insider's Portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt 50-51 (Oxford University Press 2003). In his address introducing the so-called court-packing plan, Roosevelt pulled no punches in accusing the court of acting as a policy-making body, not a judicial one, by vetoing progressive social and economic legislation passed by Congress. Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat,” March 9, 1937 (online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project). He framed the court's recent decisions as directly thwarting the will of the American people, specifically the voter-imposed mandate for Congress and the president to protect the nation against another economic depression. The court had become, in his opinion, an unbridled “super-legislature,” one against which the nation was required to “take action to save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself.” Id.

Roosevelt was not the first president to suggest a fundamental conflict between the court's power of review and the political principles of a representative government. Lincoln opined in his first inaugural address that “if the policy of the government, upon vital questions affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made, … the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.” John Nicolay and John Hay, eds, Abraham Lincoln: Collected Works, vol. 2, 5 (New York 1894). The presidents perceived a more effective government would result from a court that acted in harmony with the presidential administration, in other words, as an institution subject to the political system, not superior to it. Mario M. Cuomo, Why Lincoln Matters 149 (Harcourt, 2004).

The frustration of the executive branch is understandable. The president, under a term limit, sets out to achieve the change promised during the campaign, and the effectiveness of any administration is often measured by the speed with which such goals are effected. Jackson's 1937 speech expressly criticized the machinations of the court as preventing the political compromise necessary to make real progress. The assertion that the court's exercise of its judicial power of review is antithetical to our democratic process, however, is unsupportable. Alexander Hamilton explained that the court's power of review does not “suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former.” Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 78 (The Heritage Press ed. 1945).

The judicial branch therefore does not act in contravention of the separation of powers or the ability of Congress and the president to effect the will of the people. The Constitution is the will of the people, and unless and until the people act to change its provisions, “it is binding upon themselves collectively, as well as individually; and no presumption, or even knowledge, of their sentiments, can warrant their representatives in a departure from it.” Id. Thus, contrary to the assertions of Roosevelt and Lincoln, it cannot be posited “that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their will to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority.” Id.

Further, the tension between political expediency and judicial review complained of by Roosevelt is by no means an unintentional by-product of our tripartite Constitutional system; rather, the founders expressly intended this balance. What is criticized as inefficiency reflects a purposeful fractionalized design intended to ensure additional security to the rights of all. James Madison, Federalist No. 51 (The Heritage Press ed. 1945). If the executive branch steams forward to implement the common interest of the majority, the judiciary reflects whether the rights of the minority will remain secure. Id.

An effective judiciary therefore requires a steadfast resistance to executive overreach in order to protect, not negate, the will of the people. Almost 20 years after his speech to the New York State Bar Association, Justice Jackson advocated for such resistance through an independent judiciary and supporting legal community. He emphasized a truth that has not changed since the Constitution's creation, that “[i]t is the nature of power always to resist and evade restraints by law, just as it is the essential nature of law, as we know it, always to curb power.” Robert H. Jackson, The American Bar Center: A Testimony to Our Faith in the Rule of Law, 40 A.B.A.J. 19, 22 (1954). Although he did not divert from his belief that the law is a living doctrine, not one closed to the realities of life, this time Justice Jackson recognized the beneficial contribution of legal philosophy to ensuring that all three government branches conduct themselves with the knowledge that they operate under, not above, the law.

The importance of judicial independence to our society cannot be overstated. Circumstances will inevitably present themselves, such as those that prompted Lincoln to ask whether the integrity of one law should be permitted to threaten the whole Union (John Nicolay and John Hay, eds., Abraham Lincoln: Collected Works, vol. 2, 60 (New York 1894)), that tempt the momentary yielding of our founding principles to a claimed greater good. The bulwark of a strong and independent judiciary is necessary to protect our country against such momentary passions—compelling though they may be—for if we fail in that, we lose our very foundation.

Gerald J. Whalen is Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Plan Suit

4 minute read

'Where Were the Lawyers?' Judge Blocks Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250