Separation of Powers: A Tribute to My Father

As we celebrate Law Day and contemplate the doctrine that forms the very foundation of our government, let us commit to doing our best, as lawyers and judges, to restore our fellow citizens' trust in our core institutions.

April 30, 2018 at 03:40 PM

6 minute read

I honor my immigrant father by writing about the core principle that undergirds our democracy and preserves our liberty: the separation of powers. For him, the concept is not only theoretical, but personal. He has experienced how the balance of power anchors our freedoms, and how without it, we are lost.

You see, my father grew up under a dictatorship, which lasted more than 30 years. Unsurprisingly, after that dictatorship fell, the country did not suddenly become a model democracy. For years, the caprice of those in power continued to pass for justice, while each political party that won an election brought with it its own constitution. My father was one of the many unfortunate victims of the lack of strong democratic institutions—particularly an independent judiciary with the will to respond to the encroachment of the executive on the other branches of government. As the president of the country's powerful drivers' union, my father and his organization were responsible for disseminating information throughout the island in the pre-Internet era. As a result, he was jailed on several occasions around the time of the country's elections, his only “crime” being that he oversaw and facilitated the distribution of information that is essential for voters to make educated choices when electing their officials. He and countless others were jailed for exercising rights that many of us in the United States take for granted. So, for my father, the separation of powers was not a lofty concept taught in school; he knew it was a necessary ingredient to bring the dream of liberty and good government to fruition.

Our respect for the checks and balances enshrined in the U.S. Constitution is what has prevented tyranny from taking hold. As James Madison explained, “[t]he accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, … whether hereditary, self- appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny” (Madison, Federalist No. 47). Therefore, to have a functioning democracy, judges must be free from undue influence and pressure from the executive or legislative branches, as well as from private parties, economic interests, or politics (see Yash Vyas, “The Independence of the Judiciary: A Third World Perspective,” 11 Third World Legal Studies 127, 133-34 (1992)).

Of course, judicial independence does not mean a lack of accountability. Judges must be free even from their own prejudices (id. at 133), or at least be aware of those prejudices and recuse from cases where appropriate. Moreover, we are precluded from deciding legal questions based on our subjective feelings (id. at 135-36); we are bound by written law, precedent, and our oaths to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law. As Cardozo put it:

[J]udges, even when [we are] free, [are] still not wholly free. [We are] not to innovate at pleasure … . [We are] to draw [our] inspiration from consecrated principles … . [We are] to exercise a discretion informed by tradition, methodized by analogy, disciplined by system, and subordinate to the primordial necessity of order in the social life.

Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Nature of Judicial Process 141 (1921) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Thus, whereas judges must follow the law and, indeed, refrain from deciding questions necessarily left to “coordinate branches of government” (Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 217 (1962)), so too must the legislative and executive branches respect the Constitution, the rule of law, and the province of the courts. The alternative would inevitably lead to the rights of the people being trampled.

Growing up, my father's stories always seemed unreal and impossible, even though I experienced some of them until I was 14 and immigrated to the United States. His experience is in stark contrast to America's wonderful (albeit imperfect) experiment in democracy, where strong democratic institutions check one another's power, and where an independent judiciary answers to fundamental principles of justice, not to despots. How could anything seriously threaten to dismantle the magnificent architecture of checks and balances established in our federal and state constitutions?

I once believed that the bedrock principle of separation of powers was so integral to our culture that we no longer had to worry about structural frailties like those of developing democracies. But as we are increasingly faced with a loss of respect for fundamental values, facts, truth, reason, and the rule of law, I am no longer so sanguine. As judges, we take no position on public policy issues that are the source of vigorous debate in today's society. For example, we have no official position on immigration or health care policies. But the rule of law is not a partisan issue, nor are the core constitutional principles that ensure debate on those policies and support the administration of justice. We must insist on fundamental respect for our laws and the people they protect. Indeed, our wonderful experiment is only viable or workable in an environment of mutual respect and the protection of individual rights, which is no less important when those rights belong to those of a different national origin or persons we fear to be “foreign.”

My father is 96 now, and I cannot help but think that the America he longed for, and the dream that he made into a reality for his family, is in jeopardy. We are being tested, to be sure. But while my confidence in the “unshakable” pillars of our democracy is shaken, I believe there is reason to hope that this too shall pass. For example, according to a 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center, 83 percent of respondents said that it is “very important” to have “a system of checks and balances dividing power between the President, Congress, and the courts” to maintain a strong democracy (Pew Research Center, Report, Large Majorities See Checks and Balances, Right to Protest as Essential for Democracy at 9 (March 2, 2017).

So, as we celebrate Law Day and contemplate the doctrine that forms the very foundation of our government, let us commit to doing our best, as lawyers and judges, to restore our fellow citizens' trust in our core institutions. For if we truly value the separation of powers as vital to the preservation of liberty, our democracy will endure, and my grandchildren will be fortunate enough to grow up, like my children and I have, in a nation where power is not consolidated in the hands of the few, or in one branch of government.

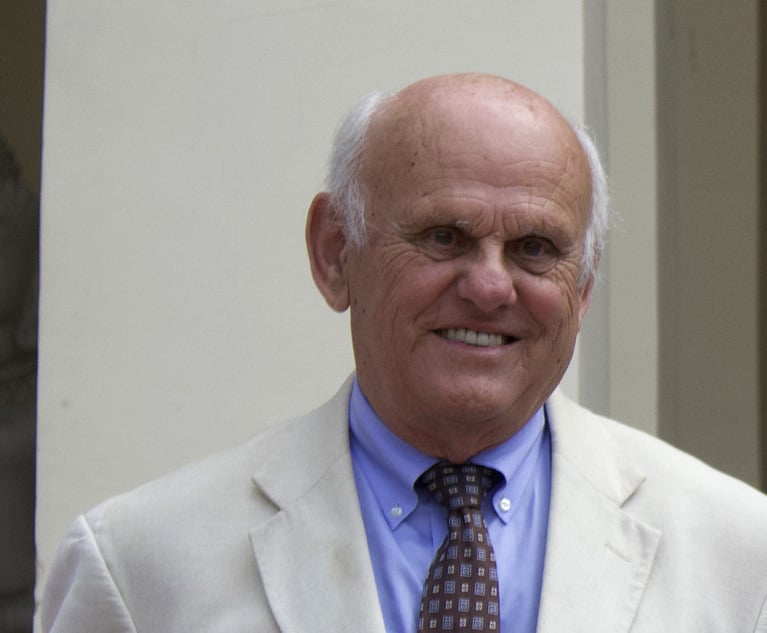

Rolando T. Acosta is Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Plan Suit

4 minute read

'Where Were the Lawyers?' Judge Blocks Trump's Birthright Citizenship Order

3 minute read

‘Catholic Charities v. Wisconsin Labor and Industry Review Commission’: Another Consequence of 'Hobby Lobby'?

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Trial Court's Sidestep of 'Batson' Deprived Defendant of Challenge to Jury Discrimination

- 2Is Your Law Firm Growing Fast Enough? Scale, Consolidation and Competition

- 3Child Custody: The Dangers of 'Rules of Thumb'

- 4The Spectacle of Rudy Giuliani Returns to the SDNY

- 5Orrick Hires Longtime Weil Partner as New Head of Antitrust Litigation

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250