Author's Resignation From the Bar Provides Fodder for Engaging Novel

The plot conflict is summed up by one quote: "Law school may teach you the law, but it doesn't teach you how to be a lawyer."

May 30, 2018 at 10:32 AM

6 minute read

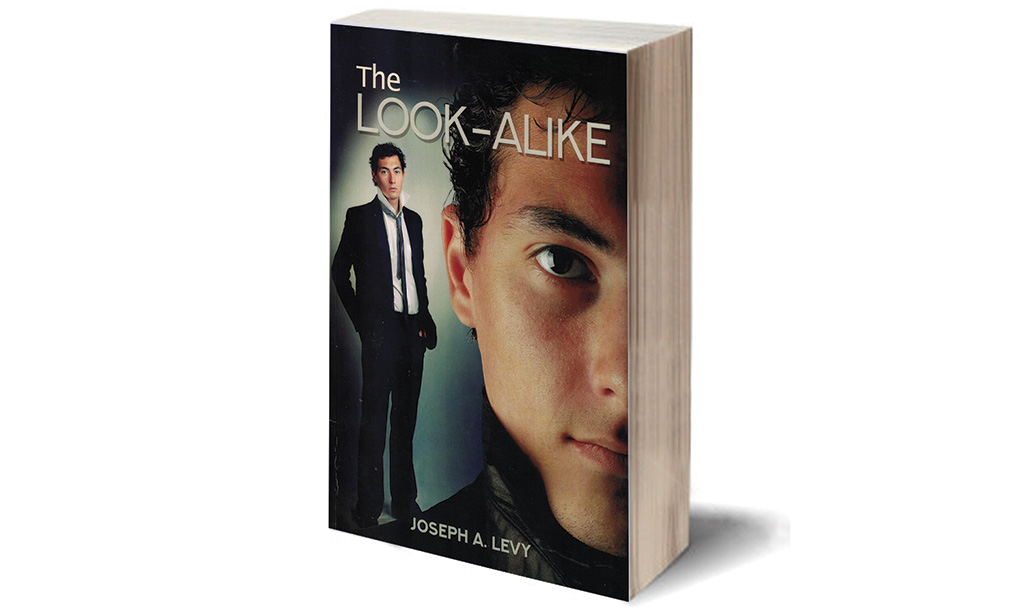

The Look-Alike

By Joseph A. Levy

Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4809-5318-5; 252 pages (paperback), $18.00

Many lawyers have found renown as authors of popular fiction. Like all writers, their personal life experiences have impacted their writings; accordingly, litigation and courtroom scenarios can be found in the fiction works of such lawyer-writers as Scott Turow, John Grisham, Linda Fairstein, Franz Kafka, and, of course, the Perry Mason stories by Erle Stanley Gardner. The plot of Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has elements from both Stevenson's background in the law profession and his cocaine addiction.

Joseph A. Levy has now joined those legions of lawyer-writers with his new tome The Look-Alike.

This reviewer has personally known Mr. Levy for more than three decades, from a time when we each resided outside of the New York metropolitan area.

The Look-Alike's story plot entails many elements from the author's personal life experiences (though many key details have been significantly altered). Mr. Levy's input for this Review was neither requested nor proffered; indeed, he was not informed of this review before its final submission to the Editor.

It is a matter of public record that in 2005, Joseph A. Levy chose to resolve the Second Department Grievance Committee's investigation of complaints against him by voluntarily resigning from the Bar. These complaints alleged “improper solicitation, failing to properly supervise his law office and failing to maintain his attorney registration,” Matter of Levy, 31 AD3d 160, 2006 NY Slip Op 04426 (2d Dept. 2006).

The Look-Alike is an autobiographical roman à clef, based upon Levy's own tribulations he experienced while in law school, the developments of which the reviewer was regularly kept apprised. The protagonist of the story is Michael Biton, a Brooklyn Law School student from a (mostly) close-knit Brooklyn Jewish family from Morocco, who undergoes a serial misadventure quite similar to Levy's own.

Biton, pursuing academic credit as a summer intern with the New York City Corporation Counsel, finds himself arrested and charged with a rape he in fact did not commit (and was nowhere near the vicinity at the time).

As Biton continually becomes mired deeper and deeper, more and more potentially exonerating evidence continues to surface. Police and government functionaries circumspectly admit their beliefs of Biton's innocence, even as they move his prosecution forward.

As the plot progresses, Biton wisely discharges his initially-retained counsel, his brother-in-law's personal general practitioner lawyer, and engages well-reputed criminal defense specialist Abe Barshefsky, to the detriment of the Biton family finances. Other than the money aspect, Biton and Barshefsky interact famously with one another. Barshefsky, who is also defending some notorious Mafiosi at the time, is big on courtroom histrionics and a sense of self-importance, but weak on legal research, which he leaves to his associate — and sometimes to Biton.

Barshefsky also effectively tolerates his investigator's abusive shakedowns of additional payments from Biton.

Biton's main obstacle is Nancy Lester, an Assistant District Attorney who, notwithstanding the oft-repeated maxim that “the prosecutor's job is to seek justice, not to get people convicted,” is obsessed with convicting Biton at all costs, ethics and fairness be damned, even as she amasses exculpatory evidence that should create a reasonable doubt. Some of this evidence was not provided to the defense, and Lester engages in many highly questionable tactics, including what arguably are conflicts of interest.

Not quite halfway through the book, it comes to Barshefsky's attention that a person bearing an uncanny resemblance to Biton also works in the same building as Biton, and also attended Brooklyn Law School. Even then, Lester continues to move her prosecution of Biton full steam ahead. There are, of course, political aspects to the story plot.

And amidst it all, Michael Biton's release on his own recognizance is continually extended, thereby enabling him to continue to live a relatively normal life throughout it all. He continues his class attendance, and becomes involved in an amorous relationship that shows great promise, but which abruptly and traumatically comes to a hopelessly unrevivable ending (or perhaps not; this is only one of several story threads that might potentially be wrought into one or more sequels to the book if the author so chooses).

The plot conflict is summed up by one line in the book, spoken by Biton's classmate Patricia Kenny: “Law school may teach you the law, but it doesn't teach you how to be a lawyer.”

The extensive dialogue in the book is well crafted. Between it and the non-dialogue narrative, each step of the criminal procedure is explained in accurate detail. This includes elucidation of what is meant by phrases such as “Rosario material,” “Brady material,” “Mapp hearing,” as well as practical elucidation of some of the fine points of the familiar Miranda rules and some valuable cross-examination tactics. Everything is explained in terms understandable to a layperson, and even the peculiarities of New York State law are compared and contrasted with those of other states. The book accordingly can be a law student's reinforcement to what is taught in Criminal Procedure classes, while simultaneously serving as a recreational reading diversion from the familiar pressures of law school.

While I do not and cannot justify or condone the transactions through which Joe Levy placed himself into the predicament that warranted his resignation from the Bar, I did wonder at the time whether the disconnect between the theoretical as taught in the law school curriculum and the actual dysfunctional realities Joe experienced firsthand gave rise to a cynicism towards the legal system, an outlook which Joe neglectfully allowed to becloud some ill-advised decisions he made. Having read The Look-Alike, I am now convinced that such was indeed the case.

The Look-Alike, then, is more than just another alluring recreational thriller for a lawyer's (or layperson's) personal bookshelf; it is a cautionary tale to which lawyers, law students, law professors, judges and prosecutors alike need to give heed.

=====================

Kenneth H. Ryesky, currently based in Petach Tikva, Israel, was a solo practitioner in East Northport and also taught Business Law at Queens College CUNY for more than two decades.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'We Learn Much From the Court's Mistakes': Law Journal Review of 'The Worst Supreme Court Decisions, Ever!'

6 minute read

'Midnight in Moscow': A Memoir From the Front Lines of Russia's War Against the West

9 minute read

'There Are Heroes in Every Story': Review of 'The Eight: The Lemmon Slave Case and the Fight for Freedom'

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Rejuvenation of a Sharp Employer Non-Compete Tool: Delaware Supreme Court Reinvigorates the Employee Choice Doctrine

- 2Mastering Litigation in New York’s Commercial Division Part V, Leave It to the Experts: Expert Discovery in the New York Commercial Division

- 3GOP-Led SEC Tightens Control Over Enforcement Investigations, Lawyers Say

- 4Transgender Care Fight Targets More Adults as Georgia, Other States Weigh Laws

- 5Roundup Special Master's Report Recommends Lead Counsel Get $0 in Common Benefit Fees

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250