EDNY Judge Rejects Qualified Immunity for Officers in Excessive Force Case

Finding that qualified immunity has evolved to the point where it can protect police officers who intentionally flout constitutional rights, a federal judge in Brooklyn declined to grant it to four police officers who broke into a man's house without a warrant while responding to a child abuse report that turned out to be false.

June 11, 2018 at 07:02 PM

5 minute read

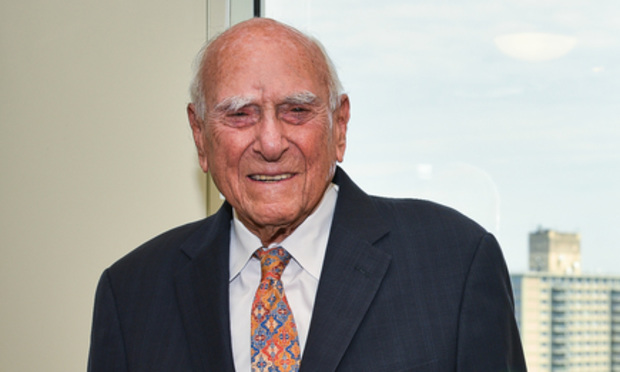

Judge Jack Weinstein. NYLJ Photo/David Handschuh. Finding that qualified immunity has evolved to the point where it can protect police officers who intentionally flout constitutional rights, a federal judge in Brooklyn declined to grant it to four police officers who broke into a man's house without a warrant while responding to a child abuse report that turned out to be false. Qualified immunity has recently “come under attack” as being too protective of police officers and standing at odds with the original intent of Section 1983 of the federal civil rights statute, U.S. District Judge Jack Weinstein of the Eastern District of New York said. “The law, it is suggested, must return to a state where some effective remedy is available for serious infringement of constitutional rights,” Weinstein said. Weinstein said he finds the U.S. Supreme Court's expansion of the doctrine in police brutality cases “particularly troubling” and that it protects “all but the plainly incompetent.” When weighing whether or not an officer is entitled to qualified immunity, the judge said, courts should apply the standard established under a 2001 Supreme Court ruling to first analyze if a constitutional violation occurred, rather than “skipping” to whether a right has been clearly established. Weinstein made the ruling in an excessive force case brought by Larry Thompson, whose sister-in-law called 911 on the night of Jan. 15, 2014, and said her two-week-old niece was being abused at Thompson's apartment in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. According to court papers, Thompson's sister-in law suffers from mental illness and lived at the apartment with Thompson and his family. New York City police officers Pagiel Clark, Paul Montefusco, Gerard Bouwmans and Phillip Romano were dispatched to the scene to investigate the child abuse report, but Thompson refused to open the door for the officers unless they produced a warrant. When Montefusco attempted to enter the apartment, Thompson tried to block his path; Thompson alleges that Montefusco threw him to the ground while other officers kicked and punched him, while the defendants say that Thompson was resisting arrest. The baby at Thompson's apartment, who had red marks on her buttocks, was inspected at a hospital, but it was determined the red marks were caused by diaper rash. Thompson was arraigned on a charge of obstructing governmental administration, but the Brooklyn District Attorney's Office moved to dismiss the charge. Weinstein said police officers can enter a home without a warrant to render emergency aid, but that an unsubstantiated 911 call does not justify warrantless entry. The judge allowed claims of unlawful entry, false arrest, excessive force, malicious prosecution, denial of a right to a fair trial and failure to intervene to move forward and set a September trial date. David Zelman, a Brooklyn solo attorney, represents Thompson. When the case was transferred to Weinstein following the death of U.S. District Judge Sandra Townes, who previously presided over the case, Zelman said the judge's initial take appeared to be that the officers had the right to enter Thompson's apartment, and thus he emphasized to the judge that there was minimal corroboration for the child-abuse accusation and that his client “did absolutely nothing wrong.” “All he did is say, 'You need a warrant to come in my house,'” Zelman said of Thompson. “I don't look these cases with dollar signs in my eyes. I look at these and see if I can prove my case.” Assistant Corporation Counsels Kavin Thadani and Matthew Bridge of the city's Law Department appeared for the officers. A Law Department spokesman said it is "considering our legal options." While denials of qualified immunity are not uncommon, the fact that a federal district judge would use a ruling to level a broader critique of how the courts have applied the doctrine doesn't happen frequently, said UCLA School of Law professor Joanna Schwartz, whose work is cited in Weinstein's 29-page ruling. Also among those who have spoken out on qualified immunity is Judge Jon Newman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit who said in a 2016 column published by The Washington Post that the doctrine should be abolished altogether. Schwartz said the Supreme Court's original policy justifications for qualified immunity, established in a 1967 ruling, were to shield police officers from financial liability so they would not be disinclined to perform their jobs. However, she said, the balance has shifted over the years away from governmental accountability to a stronger emphasis on protecting police from liability. And, as Weinstein noted in his ruling, the doctrine appears to have moved away from the high court's original policy goals, as police officers tend to be indemnified and that invoking a qualified immunity defense also uses government resources for litigating the defense. “The court has really shifted its explanation of why the doctrine exists over the years,” Schwartz said.

Judge Jack Weinstein. NYLJ Photo/David Handschuh. Finding that qualified immunity has evolved to the point where it can protect police officers who intentionally flout constitutional rights, a federal judge in Brooklyn declined to grant it to four police officers who broke into a man's house without a warrant while responding to a child abuse report that turned out to be false. Qualified immunity has recently “come under attack” as being too protective of police officers and standing at odds with the original intent of Section 1983 of the federal civil rights statute, U.S. District Judge Jack Weinstein of the Eastern District of New York said. “The law, it is suggested, must return to a state where some effective remedy is available for serious infringement of constitutional rights,” Weinstein said. Weinstein said he finds the U.S. Supreme Court's expansion of the doctrine in police brutality cases “particularly troubling” and that it protects “all but the plainly incompetent.” When weighing whether or not an officer is entitled to qualified immunity, the judge said, courts should apply the standard established under a 2001 Supreme Court ruling to first analyze if a constitutional violation occurred, rather than “skipping” to whether a right has been clearly established. Weinstein made the ruling in an excessive force case brought by Larry Thompson, whose sister-in-law called 911 on the night of Jan. 15, 2014, and said her two-week-old niece was being abused at Thompson's apartment in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. According to court papers, Thompson's sister-in law suffers from mental illness and lived at the apartment with Thompson and his family. New York City police officers Pagiel Clark, Paul Montefusco, Gerard Bouwmans and Phillip Romano were dispatched to the scene to investigate the child abuse report, but Thompson refused to open the door for the officers unless they produced a warrant. When Montefusco attempted to enter the apartment, Thompson tried to block his path; Thompson alleges that Montefusco threw him to the ground while other officers kicked and punched him, while the defendants say that Thompson was resisting arrest. The baby at Thompson's apartment, who had red marks on her buttocks, was inspected at a hospital, but it was determined the red marks were caused by diaper rash. Thompson was arraigned on a charge of obstructing governmental administration, but the Brooklyn District Attorney's Office moved to dismiss the charge. Weinstein said police officers can enter a home without a warrant to render emergency aid, but that an unsubstantiated 911 call does not justify warrantless entry. The judge allowed claims of unlawful entry, false arrest, excessive force, malicious prosecution, denial of a right to a fair trial and failure to intervene to move forward and set a September trial date. David Zelman, a Brooklyn solo attorney, represents Thompson. When the case was transferred to Weinstein following the death of U.S. District Judge Sandra Townes, who previously presided over the case, Zelman said the judge's initial take appeared to be that the officers had the right to enter Thompson's apartment, and thus he emphasized to the judge that there was minimal corroboration for the child-abuse accusation and that his client “did absolutely nothing wrong.” “All he did is say, 'You need a warrant to come in my house,'” Zelman said of Thompson. “I don't look these cases with dollar signs in my eyes. I look at these and see if I can prove my case.” Assistant Corporation Counsels Kavin Thadani and Matthew Bridge of the city's Law Department appeared for the officers. A Law Department spokesman said it is "considering our legal options." While denials of qualified immunity are not uncommon, the fact that a federal district judge would use a ruling to level a broader critique of how the courts have applied the doctrine doesn't happen frequently, said UCLA School of Law professor Joanna Schwartz, whose work is cited in Weinstein's 29-page ruling. Also among those who have spoken out on qualified immunity is Judge Jon Newman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit who said in a 2016 column published by The Washington Post that the doctrine should be abolished altogether. Schwartz said the Supreme Court's original policy justifications for qualified immunity, established in a 1967 ruling, were to shield police officers from financial liability so they would not be disinclined to perform their jobs. However, she said, the balance has shifted over the years away from governmental accountability to a stronger emphasis on protecting police from liability. And, as Weinstein noted in his ruling, the doctrine appears to have moved away from the high court's original policy goals, as police officers tend to be indemnified and that invoking a qualified immunity defense also uses government resources for litigating the defense. “The court has really shifted its explanation of why the doctrine exists over the years,” Schwartz said. NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: Court Rules on Judgment Motions Over Police Killing of Pet Dog While Executing Warrant

A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

13 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Buyer Beware:Continuity of Coverage in Legal Malpractice Insurance

- 2‘Listen, Listen, Listen’: Some Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

- 3BCLP Joins Saudi Legal Market with Plans to Open Two Offices

- 4White & Case Crosses $4M in PEP, $3B in Revenue in 'Breakthrough Year'

- 5Thursday Newspaper

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250