NYC, NY State Spar With Renters and Owners Over Property Tax Scheme

The suit takes aim at an “inequitable and antiquated” property tax system throughout New York City in which similarly situated properties are saddled with “widely different” tax burdens based on where they are located in the city.

June 13, 2018 at 07:58 PM

5 minute read

Former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman. (Photo: Tim Roske) The governments of New York City and New York state are fighting to dismiss a suit by a group of property owners and renters who say that the city's property tax system unconstitutionally imposes lower tax rates on some wealthy New Yorkers' properties than those in poorer neighborhoods. The suit, filed by a group called Tax Equity Now, which is represented by a team from Latham & Watkins that includes Jonathan Lippman, the former chief judge of New York's judiciary, takes aim at an “inequitable and antiquated” property tax system throughout New York City in which similarly situated properties are saddled with “widely different” tax burdens based on where they are located in the city. “No one thinks the tax policy in the city of New York is good,” said James Brandt of Latham & Watkins on Wednesday in oral arguments before Acting Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Gerald Lebovits on motions to dismiss the case. “The city itself admits right front and center that the tax system is broken.” For example, according to the suit, the city's Finance Department valued a 68-unit apartment building at 960 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan at $48.5 million, but one of the units in that building sold for $70 million in 2014. The disparities in value can also be seen within the each of the five boroughs, the plaintiffs allege, and appear to fall along racial lines: according to testimony from the city's own budget office, a $500,000 house in the relatively affluent and majority-white Park Slope section of Brooklyn would pay less than $1,300 in property taxes, while the owner of a house with the same value in Brooklyn's Canarsie neighborhood, where the population is about one-quarter white, would pay about $5,460. They argue that the disparities in the city's property tax system hurts renters because it tends to undervalue cooperatives and condominiums relative to rental apartments, thus shifting the tax burden to landlords who ultimately pass the costs along to renters. Latham & Watkins attorneys Richard Bress and Michael Bern are also appearing for the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs request that Lebovits issue a declaration that the city's property tax scheme and the state statutes that govern it are unconstitutional. But in motions to dismiss, lawyers for both the city and the state argue that Tax Equity Now lacks standing to bring the suit and that their claim of violations of the Fair Housing Act should be rejected because they have not proved that anyone has lost housing because of the alleged disparities in property tax assessment. At oral arguments, Assistant Attorney General Andrew Amer, arguing for the state, said the plaintiffs' argument that the city's property tax scheme hurts renters amounts to “wild speculation.” “Renters do not pay property taxes,” Amer said. “They never have, and they never will. It's the landlords.” Assistant Corporation Counsels Joshua Sivin and Andrea Chan appeared at oral arguments for the city. Lebovits reserved judgment on the motions to dismiss. The city estimates that it will collect more than $27 billion in property taxes in its 2018-19 fiscal year, the largest line item in the $60.2 billion it expects to collect in total tax revenue during the fiscal year, according to city budget documents. The arguments in the legal battle, which has made odd partners of big-time real estate powerhouses like the Durst Organization and renters of modest means, came within two weeks after Mayor Bill de Blasio and New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson announced the creation of an advisory commission to study reforms to the city's property tax system, in which de Blasio lamented a system that is “ too opaque, too complex and just feels unfair.” The case has also put members of the New York City Council at odds with the city's Law Department over whether or not the members could file an amicus brief and appear with a private attorney in the case on behalf of the plaintiffs. On that issue, Lebovits sided with the Corporation Counsel, finding that, because the council members are acting in their official capacities by attempting to join the case, no one but the Corporation Counsel may represent them. The council members are appealing the ruling to the Appellate Division, First Department.

Former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman. (Photo: Tim Roske) The governments of New York City and New York state are fighting to dismiss a suit by a group of property owners and renters who say that the city's property tax system unconstitutionally imposes lower tax rates on some wealthy New Yorkers' properties than those in poorer neighborhoods. The suit, filed by a group called Tax Equity Now, which is represented by a team from Latham & Watkins that includes Jonathan Lippman, the former chief judge of New York's judiciary, takes aim at an “inequitable and antiquated” property tax system throughout New York City in which similarly situated properties are saddled with “widely different” tax burdens based on where they are located in the city. “No one thinks the tax policy in the city of New York is good,” said James Brandt of Latham & Watkins on Wednesday in oral arguments before Acting Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Gerald Lebovits on motions to dismiss the case. “The city itself admits right front and center that the tax system is broken.” For example, according to the suit, the city's Finance Department valued a 68-unit apartment building at 960 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan at $48.5 million, but one of the units in that building sold for $70 million in 2014. The disparities in value can also be seen within the each of the five boroughs, the plaintiffs allege, and appear to fall along racial lines: according to testimony from the city's own budget office, a $500,000 house in the relatively affluent and majority-white Park Slope section of Brooklyn would pay less than $1,300 in property taxes, while the owner of a house with the same value in Brooklyn's Canarsie neighborhood, where the population is about one-quarter white, would pay about $5,460. They argue that the disparities in the city's property tax system hurts renters because it tends to undervalue cooperatives and condominiums relative to rental apartments, thus shifting the tax burden to landlords who ultimately pass the costs along to renters. Latham & Watkins attorneys Richard Bress and Michael Bern are also appearing for the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs request that Lebovits issue a declaration that the city's property tax scheme and the state statutes that govern it are unconstitutional. But in motions to dismiss, lawyers for both the city and the state argue that Tax Equity Now lacks standing to bring the suit and that their claim of violations of the Fair Housing Act should be rejected because they have not proved that anyone has lost housing because of the alleged disparities in property tax assessment. At oral arguments, Assistant Attorney General Andrew Amer, arguing for the state, said the plaintiffs' argument that the city's property tax scheme hurts renters amounts to “wild speculation.” “Renters do not pay property taxes,” Amer said. “They never have, and they never will. It's the landlords.” Assistant Corporation Counsels Joshua Sivin and Andrea Chan appeared at oral arguments for the city. Lebovits reserved judgment on the motions to dismiss. The city estimates that it will collect more than $27 billion in property taxes in its 2018-19 fiscal year, the largest line item in the $60.2 billion it expects to collect in total tax revenue during the fiscal year, according to city budget documents. The arguments in the legal battle, which has made odd partners of big-time real estate powerhouses like the Durst Organization and renters of modest means, came within two weeks after Mayor Bill de Blasio and New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson announced the creation of an advisory commission to study reforms to the city's property tax system, in which de Blasio lamented a system that is “ too opaque, too complex and just feels unfair.” The case has also put members of the New York City Council at odds with the city's Law Department over whether or not the members could file an amicus brief and appear with a private attorney in the case on behalf of the plaintiffs. On that issue, Lebovits sided with the Corporation Counsel, finding that, because the council members are acting in their official capacities by attempting to join the case, no one but the Corporation Counsel may represent them. The council members are appealing the ruling to the Appellate Division, First Department.This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

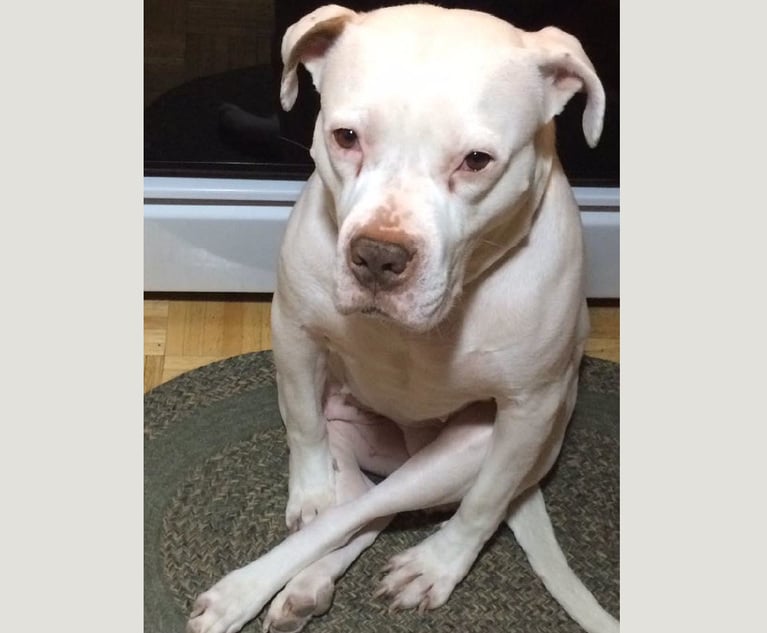

Decision of the Day: Court Rules on Judgment Motions Over Police Killing of Pet Dog While Executing Warrant

A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

13 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Exceptional Growth Becoming the Rule? Demand and Rate Hikes Drove Strong Year for Big Law

- 2Dentons Taps D.C. Capital Markets Attorney for New US Managing Partner

- 3Auto Dealers Ask Court to Pump the Brakes on Scout Motors’ Florida Sales

- 4German Court Orders X to Release Data Amid Election Interference Concerns

- 5Litigation Trends to Watch From Law.com Radar: Suits Strike at DEI Policies, 'Meme Coins' and Infractions in Cannabis Labeling

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250