Rage Against the (Eviction) Machine: With a Possible Solution

Could a certificate of merit requirement imposed on landlords' attorneys in housing court help stem the tide of frivolous claims and the erosion of affordable housing across the country?

July 27, 2018 at 09:00 AM

6 minute read

Over 2 million evictions are carried out in the United States every year. Making matters worse, in many of these cases, low-income tenants face their eviction—often on trumped up charges—without the benefit of legal representation, even though they often meet federal guidelines for free legal assistance. The budget of the Legal Services Corporation, the federal agency that dispenses aid to non-profit groups throughout the country to provide representation to low-income Americans—in red states and blue, in rural counties and urban centers—has been slashed considerably in the last ten years, with no sign that Congress will increase its budget to meet the glaring need.

What's more, the human price of eviction is immense. The fact that many tenants face bogus eviction cases without the benefit of a lawyer, should give everyone concerned about income inequality, racial justice, rural justice, and the rule of law great pause. Historically, over 95 percent of tenants face harassing evictions without the benefit of legal representation. The De Blasio Administration in New York City has committed hundreds of millions of dollars to help tip the balance of legal power by supplying lawyers to many low-income families facing eviction, San Francisco voters have approved a measure to provide representation to tenants facing eviction, and other cities, like Newark, NJ, may follow suit. But there may be another fix, one that might not be so costly, that could also help prevent senseless evictions on baseless grounds: make landlords' lawyers confirm the merits of their clients' claims.

My former work as a housing attorney in New York City spanned the fourteen years between the recession of the early 1990s and the Great Recession of the late 2000s. I represented low-income tenants facing penny-ante speculators in Harlem and Washington Heights in 1992, and middle-income retirees in Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village staring down high rolling predatory investors at the height of the housing bubble in the late 2000s. Regardless of the neighborhood or the stakes, the tactics of some unscrupulous landlords were always the same: use trumped up legal charges to harass tenants into abandoning their apartments. This would then enable the landlords to manipulate the rent laws so they could charge market rents. And not just any market rents, New York City market rents, which are simply unaffordable to many in a city of economic extremes.

We know the perverse market incentives to bring such cases are simply too high for these landlords to resist. Their lawyers should know better than to bring baseless claims, however. In fact, they have an ethical obligation to know better. Indeed, lawyers are duty-bound to only assert good faith legal claims. Sometimes, however, they need a little boost to be reminded of this obligation, especially when the financial incentives might be such that a lawyer might be less scrupulous about honoring his or her ethical obligations. It turns out, in such times, courts can step in to ensure that lawyers are reminded of these obligations and honor them.

Indeed, in the midst of the foreclosure crisis in the depth of the Great Recession, New York's court system took a simple step to ensure that banks did not bring frivolous foreclosure cases. The court system or the legislature could take similar measures today to help ensure housing justice in New York's neighborhoods and preserve the fabric of our low- and middle-class communities, which are eroding too quickly, changing the face of New York City, possibly forever.

In 2010, when the so-called “Robo-Sign” scandal broke, it was revealed that bank officials were making baseless claims against borrowers alleged to be in default on their mortgages. New York's court system created a court rule, which the legislature later codified in a state statute, that said that any lawyer submitting a residential mortgage foreclosure action had to file what has come to be known as a “Certificate of Merit”: a sworn statement made by the lawyer under the penalties of perjury that attests to the fact that the lawyer has reviewed the allegations of his or her client in pursuing the action and those claims have a firm grounding in fact and law. The lawyers must also give details about the inquiry he or she conducted, including naming the individual or individuals with whom the lawyer spoke when investigating the client's claims. After the rule was first instituted in late 2010, mortgage foreclosure filings dropped nearly eighty percent, presumably because lawyers were not willing to file these certificates of merit when their clients could not establish the basis for their claims to the lawyers' satisfaction.

As recent reporting made clear, and this is consistent with the experience of thousands upon thousands of tenants, many housing court filings are baseless, not unlike the frivolous foreclosure filings of nearly a decade ago. Could a certificate of merit requirement imposed on landlords' attorneys in housing court help stem the tide of frivolous claims and the erosion of affordable housing across the country?

In New York City, for every baseless eviction of a rent-regulated apartment, another unit of affordable housinggoes up in proverbial smoke. It costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to build a single apartment of affordable housing in New York City. Although many cities and rural communities do not have the same protective rent laws as New York, the human and financial costs associated with evictions are staggering, as Harvard's Matthew Desmond lays out so powerfully in his book Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. Could a simple, no-cost fix—asking landlords' attorneys to certify the merit of their clients' claims under the penalties of perjury—help keep people in their homes, maintain affordable housing, combat economic inequality and honor the rule of law? It seems like such a modest measure could have considerable positive results. It certainly could not make the situation any worse.

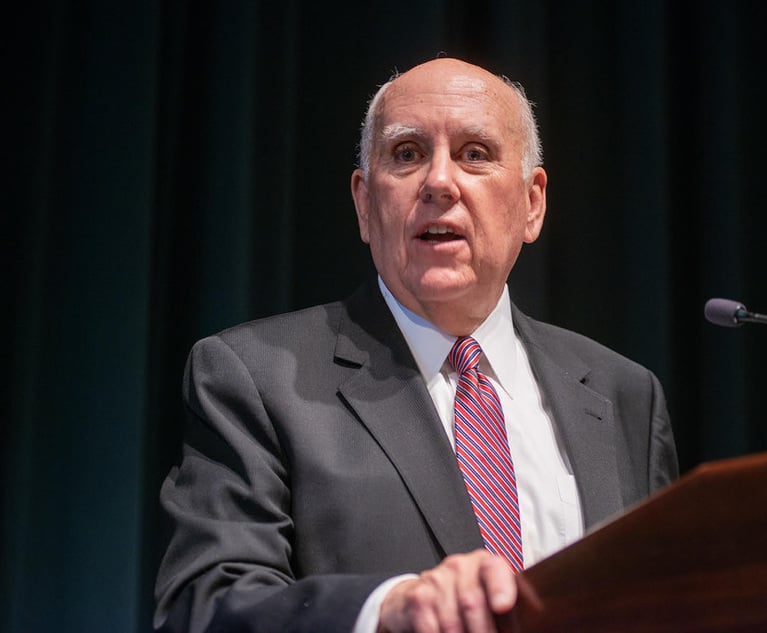

Ray Brescia is the Harold R. Tyler Chair in Law and Technology and a professor of law at Albany Law School; he spent fourteen years representing tenants in housing court in New York City at several non-profit organizations.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

For Safer Traffic Stops, Replace Paper Documents With ‘Contactless’ Tech

4 minute read

Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley: American Painters in London

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1The Evolution of a Virtual Court System

- 2New Acquitted Conduct Guideline: An Analysis

- 3Considering the Implications of the 2024 Presidential Election for Jurors in White Collar Cases

- 42024 in Review: Judges Met Out Punishments for Ex-Apple, FDIC, Moody's Legal Leaders

- 5What We Heard From Litigation Leaders in 2024

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250