New Ethics Opinion on Litigation Funding Gets It Wrong

The New York City Bar ethics committee recently issued Formal Opinion 2018-5: Litigation Funders' Contingent Interest in Legal Fees.

August 31, 2018 at 12:27 PM

10 minute read

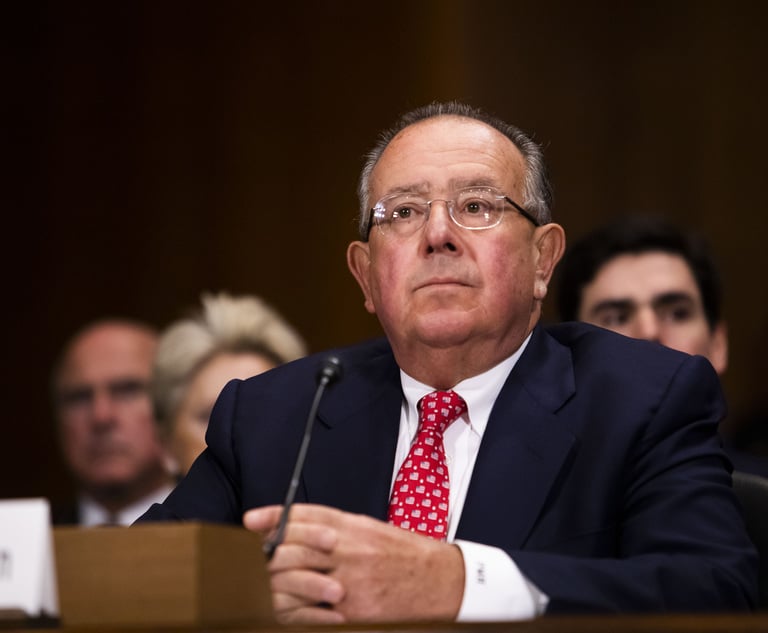

Anthony E. Davis

Anthony E. Davis

The New York City Bar ethics committee (the committee) recently issued Formal Opinion 2018-5: Litigation Funders' Contingent Interest in Legal Fees (Opinion 2018-5). For the reasons we will set out in this article, Opinion 2018-5 incorrectly interprets New York Rule of Professional Conduct (RPC) 5.4 dealing with lawyer independence, specifically determines to be unethical activities far less intrusive on lawyer independence than many lending practices that have been accepted and used by almost every law firm for decades, and drives a wedge between settled New York case law and—if the committee's interpretation of RPC 5.4 were correct—the ethics rules. Based on our conclusions, we call on the committee to withdraw Opinion 2018-5 for reconsideration, and suggest that before it again sees the light of day the committee should engage in an extensive process of consultation that would include litigation funders and the wider profession.

Let us start with what Opinion 2018-5 addresses and concludes. The question posed in the opinion is: “May a lawyer enter into a financing agreement with a litigation funder, a nonlawyer, under which the lawyer's future payments to the funder are contingent on the lawyer's receipt of legal fees or on the amount of legal fees received in one or more specific matters?” And the opinion specifically concludes that lawyers may not enter into such agreements because they are impermissible under RPC 5.4(a) which provides that “[a] lawyer or law firm shall not share legal fees with a nonlawyer.” And the committee expressly recognizes that this restriction is intended “to protect the lawyer's professional independence of judgment. Rule 5.4 Cmnt. [1]” The core of Opinion 2018-5 is contained in the following paragraph:

“Lawyer-funder arrangements do not necessarily involve impermissible fee sharing under Rule 5.4(a). The rule is not implicated simply because the lawyer's payments to a funder come from income derived from legal fees. But Rule 5.4(a) forbids a funding arrangement in which the lawyer's future payments to the funder are contingent on the lawyer's receipt of legal fees or on the amount of legal fees received in one or more specific matters. That is true whether the arrangement is a non-recourse loan secured by legal fees or it involves financing in which the amount of the lawyer's payments varies with the amount of legal fees in one or more matters. Rule 5.4(a) has long been understood to apply to business arrangements in which lawyers' payments to nonlawyers are tied to legal fees in these types of ways.”

Understanding the Underlying Purpose of Rule 5.4(a)

Rule 5.4 deals with a serious issue: the professional independence of lawyers. This is an important core value of the profession and is intended to ensure that nonlawyers don't insert their judgment into the lawyer-client relationship. RPC 5.4(a), with which this opinion is concerned, says that a nonlawyer cannot “share” a fee with a lawyer. Most obviously, it prevents a nonlawyer from crossing the line from being an agent of the lawyer to becoming a principal vis-à-vis the client's legal representation. Under this rule, a lawyer, no matter how well-intentioned, cannot be allowed to share power over a client's legal representation with a nonlawyer.

Why Is 'Traditional' Lending to Lawyers Different?

According to Opinion 2018-5, “recourse” loans are outside the scope of Rule 5.4(a)'s jurisdiction because they do not involve “fee sharing.” In a recourse loan, a lawyer absolutely promises to repay a nonlawyer regardless of whether she earns a fee from a client. But if fee-sharing is interference with independent professional judgment by means of a financing arrangement, why are recourse loans per se beyond Rule 5.4(a)'s reach? Sometimes banks are not content with recourse to a lawyer's assets to protect themselves; they will impose a condition, in the form of a covenant from the lawyer which, if in default, will trigger new terms and that may include permitting the bank to take control over the operations of the firm. In the aftermath of the crisis of 2008, lenders seized extraordinary control over law firms' expenditures, to the point where one major bank was reported to have limited firm expenditures on salaries and staffing. How could this not affect the ability of a firm to devote the resources it independently believed necessary for its clients ends? How is this not a direct limitation on, and arguably far more dangerous for the professional independence of a lawyer, than a simple nonrecourse loan, or a deal to pay 10 percent of earned fees across an average of 10 cases, with a funder who has no right to control how the lawyer runs her firm?

If Opinion 2018-5 is correct, lawyers and law firms may agree to covenants permitting banks to seriously influence the firm's operations based on default in payment of the loan, secured by all of the firm's fees billed but not yet paid—but may not agree to a non-recourse loan, where the lender has no power over the firm at all, simply because the loan is secured entirely by fees which may never be earned. This outcome is ridiculous if the principle on which the distinction rests is the protection of the lawyers' independence.

The Consequences of Taking the Committee Literally

Rule 5.4(a) ought to be interpreted to permit lawyers to access all kinds of financing, regardless of whether it is recourse or nonrecourse. The committee wants something else—a formal test that rejects any nonrecourse finance agreement between a lawyer and a nonlawyer. Opinion 2018-5 would, if taken literally, threaten much of the financing that many in the profession take for granted today.

The heart of the opinion is the determination that loans secured only by anticipated fees are prohibited by its reading of Rule 5.4(a). Yet the committee recognizes, as it must, that conventional lending often involves a mix of collateral; firms and lawyers will often give a security interest in presently earned and future receivables. But those future receivables are nothing more than unearned fees; if we are to take the opinion literally, are we to say that when law firms grant a security interest in future accounts receivable, they are acting unethically? If that is the case, then why should a bank that receives a security interest in these future receivables be able to place a lien on them, superior to the claims of unsecured creditors? If the committee is correct, then many loans collateralized by future receivables may even be in default, given that some of the collateral could not have been pledged by the law firm.

Driving a Wedge between Settled Case Law and the Rules

Critically, courts have interpreted Rule 5.4(a) without resorting to the committee's radical conclusions, and the committee should have listened to what caselaw says about the relationship between contingent financing and legal ethics.

Peter Jarvis, a national authority on legal ethics, has already commented on 2018-5 in his law firm's blog. He writes:

“As a key component of its conclusion, the opinion limits its discussion of three significant judicial decisions in New York to a footnote in which the opinion attempts to distinguish them. According to the opinion, Hamilton Capital VII, LLC v. Khorrami, LLP, No. 650791/2015, 48 Misc.3d 1223(A), 2015 WL 4920281 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 17, 2015), Lawsuit Funding, LLC v. Lessoff, No. 650757/2012, 2013 WL 6409971 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Dec. 4, 2013), and Heer v. North Moore Street Developers, LLC,140 A.D.3d 675, 36 N.Y.S.3d 93 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2016), stand solely for the proposition that a lawyer who obtains commercial litigation funding cannot use the violation of RPC 5.4(a) as a justification for refusing to pay the funder. However, that is not what these cases say. See https://www.hklaw.com/publications/New-York-City-Bar-Opinion-on-Commercial-Litigation-Funding-Raises-Concerns-08-20-2018/.”

We agree with Jarvis, who notes that the Lessoff court explicitly adopted the language of an earlier Delaware case, PNC Bank v. Berg, which dealt with two parties who claimed to have been assigned the same unearned (future) fees by a lawyer. The second party claimed that the first party could not have had a security interest since the lawyer could not have assigned an interest in future fees without violating Rule 5.4(a). The Delaware court said, “The Rules of Professional Conduct ensure that attorneys will zealously represent the interests of their clients, regardless of whether the fees the attorney generates from the contract through representation remain with the firm or must be used to satisfy a security interest” and “there is no real 'ethical' difference whether the security interest is in contract rights (fees not yet earned) or accounts receivable (fees earned) in so far as Rule of Professional Conduct 5.4, the rule prohibiting the sharing of legal fees with a nonlawyer, is concerned.” Hamilton Capital endorsed this interpretation of Rule 5.4(a), noting that, not only was such financing not “impermissible fee sharing with a non-lawyer,” it “promotes the sound public policy of making justice accessible to all, regardless of wealth.”

Also notable is the fact that at least two of these cases, and especially Hamilton Capital, make the very important additional point that there are very strong public policy reasons for allowing non-recourse findings in the context of access to justice—pointing out that a lawyer/client team should be able to arrange financing so they can compete effectively with well-capitalized adversaries. Forbidding financing merely because a contingency fee is involved substantially undermines that important policy goal since contingency fees are the only realistic way non-rich people can prosecute complex civil claims.

These courts took the purpose of Rule 5.4(a) seriously, and came to the conclusion that contingent financing was not a per se violation of the rule. Furthermore, the opinion fails to acknowledge the many cases, in addition to the three it cites, which reflect the degree to which courts accept the very practices that the committee deems unethical. In a case like Brandes v. North Shore University Hospital, 856 N.Y.S.2d 496 (Sup. Ct. 2008), what is remarkable is how unremarkable the court regarded the fact that the lawyer secured his loan with an unearned contingent fee. The committee, in our opinion, failed to take seriously the evidence that has accumulated over decades that judges do not believe that contingent financing through fees is a violation of Rule 5.4(a).

Conclusion

For each of the reasons we have sought to articulate, Opinion 2018-5 is, at best, ill-considered.

It creates distinctions between the loss of independence of lawyers who engage in traditional borrowing from their banks—where they place all of their receivables at the ultimate mercy of the ender if they default—and the supposed greater loss of independence where instead the lawyer borrows based on the results of specific cases, where the lender has no recourse if the cases fail to yield those results. Such an interpretation is, surely, absurd. It also creates an untenable situation for New York lawyers, where the case law permits such arrangements, those arrangements have now been called into question. We urge the committee to withdraw and reconsider the opinion, hopefully after undertaking a wide ranging consultation including the profession (beyond the composition of the committee itself) and the litigation funders.

Anthony E. Davis is a partner of Hinshaw & Culbertson and a past president of the Association of Professional Responsibility Lawyers.

Anthony J. Sebok is a professor of law and co-director of the Jacob Burns Center for Ethics in the Practice of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. He is a consultant to Burford Capital.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: Judge Rules Brutality Claims Against Hudson Valley Police Officer to Proceed to Trial

Skadden and Steptoe, Defending Amex GBT, Blasts Biden DOJ's Antitrust Lawsuit Over Merger Proposal

4 minute read

Read the Document: DOJ Releases Ex-Special Counsel's Report Explaining Trump Prosecutions

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 2Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

- 3'We Neither Like Nor Dislike the Fifth Circuit'

- 4Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

- 5Senior Associates' Billing Rates See The Biggest Jump

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250