A Series of Rare Appellate Reversal Orders, All From One Queens Justice's Courtroom

Queens Supreme Court Justice Ronald Hollie has repeatedly interjected himself into trial proceedings, forcing appellate panels over the past two years to order new trials before new judges at least four times.

September 16, 2018 at 11:55 PM

6 minute read

On Sept. 12, the Appellate Division, Second Department, issued an opinion reversing the conviction of Lutchman Sookdeo on gang-related assault charges. A jury found him guilty in February 2017 on a number of offenses, and the appellate panel, for its part, said it found no reason to question the jury's wisdom based on the evidence against Sookdeo.

A new trial was needed, the panel—composed of Associate Justices John Leventhal, Jeffrey Cohen, Sylvia Hinds-Radix and Angela Iannacci—said, because the judge who handled the case, Queens Supreme Court Justice Ronald Hollie, “conducted excessive and prejudicial questioning of trial witnesses.”

Hollie, the appellate panel found, interjected during the questioning of multiple witnesses, eliciting “step-by-step details” about how Sookdeo was identified as a suspect by witnesses, and “generally created the impression that [he] was an advocate” for the prosecution.

“Under the circumstances, the court's improper interference deprived the defendant of a fair trial, and a new trial before a different justice is warranted,” the panel said.

Appellate courts generally give lower court judges enormous deference as to how they manage their trials. Reversals of convictions are routine enough and court officials at every level—from appellate to trial courts, the federal branch down to the local—generally push back against attempts to elevate higher court reversals of lower courts as anything more than the process of justice at work.

But the appellate decision in Hollie's case is just the latest in a series of at least four now within the last two years that follow a pattern of judicial interference at trial resulting in a reversal and remand for a new one before a different judge. The results are drawing questions from observers about the levelness of the playing field for defendants entering Hollie's court, as well court administrators' abilities to address reoccurring issues among the bench.

“That's four reversals for this sort of thing in the last year and a half—that's very unusual,” Legal Aid Society criminal appeals bureau supervising attorney Richard Joselson told the New York Law Journal.

'It Certainly Raises Questions'

Legal Aid represented some of the defendants whose cases were sent back to the Queens court for retrial. Joselson noted that in each case, the defendant is likely sitting in an upstate prison while his or her case wends its way through the appellate process. Among these cases, that has meant at times years between conviction and the ordering of a new trial.

Beyond the reversal itself, Joselson said there are no automatic consequences for these kinds of judicial issues.

“It certainly raises questions about whether there's really any significant incentive to alter the behavior,” he said.

There was a point at which the appellate court appeared to defer to Hollie. In 2014, an appellate panel of Associate Justices Mark Dillon, L. Priscilla Hall, Leonard Austin and Betsy Barros affirmed Davindra Jadu's attempted robbery and grand larceny conviction. Hollie's “participation in the proceedings did not deprive the defendant of a fair and impartial trial,” the panel found.

The panel went on to note, somewhat unusually, that “any potential prejudice to the defendant was minimized by the trial court's instructions advising the jury that the court had no opinion concerning the case [.]”

The panel doesn't expound on the details of Hollie's actions at trial, making it impossible to compare that case to what followed. What is clear is that subsequent panels no longer saw deference as warranted.

In a February 2017 order, the panel composed of Associate Justices William Mastro, Leonard Austin, Robert Miller and Joseph Maltese reviewed Yushumpree Davis' conviction on weapons charges in July 2013. Hollie was again found to have “conducted excessive and prejudicial questioning of trial witnesses,” requiring a new trial before a different judge. As was the situation in the Sookdeo appeal, the panel noted that defense counsel did not object to the questioning of witnesses by the court. The panel's decision was reached in the “exercise of our interest of justice jurisdiction.”

Months later in June 2017, a panel of Associate Justices Austin, Maltese, Cohen and Colleen Duffy detailed how, during the trial of Dylesha Robinson that led to a jury conviction on assault and weapons charges, Hollie “exercised little or no restraint in questioning the witnesses.”

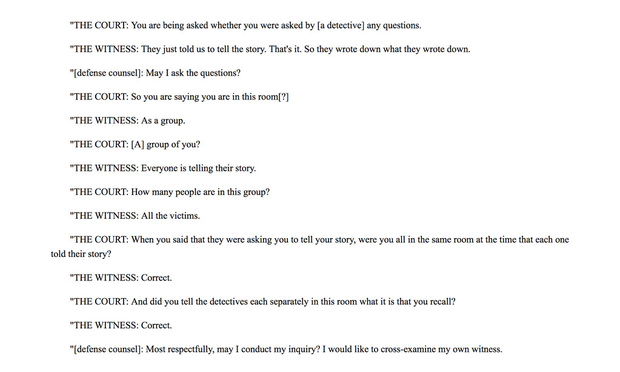

The panel quoted trial transcripts in which Hollie “redirected the inquiry and blunted the force of counsel's attempt to impeach” a complaining witness on cross-examination, leaving the defense attorney little choice to ask, repeatedly, for the judge to stop.

“Most respectfully, may I conduct my inquiry? I would like to cross-examine my own witness,” the attorney is quoted saying to Hollie. See transcript embedded with this story.

More recently, in April, the panel composed of Associate Justices Mastro, Cohen, Sheri Roman and Sandra Sgroi again reversed a conviction, this time Christopher Hinds' 2014 robbery conviction from 2014, ordering a new trial before a new judge. The panel found that Hollie had interjected himself into the questioning of witnesses more than 50 times, asking more than 400 questions, including during testimony provided by police officers.

'Backward Looking'

As Legal Aid's Joselson noted, while the appellate-level reversals have occurred over the last 18 months or so, the underlying trials range from 2012 to 2017, leaving open the possibility that other convictions in Hollie's court still working their way through the system could face similar scrutiny.

“in this area, trial judges get a lot of leeway. It's only when it reaches a certain point when this appellate court or any appellate court is going to intercede as they did here,” Joselson said. “It seems quiet possible that there may be additional cases that are still in the appellate pipeline that have similar issues.”

Hollie did not respond to a request for comment. His chambers directed questions about the decisions to the Office of Court Administration. In an email responding to an inquiry by the Law Journal, OCA spokesman Lucian Chalfen said the cases at issue all occurred “in a short period of time” and were “backward looking.”

“Judge Hollie is aware of the reversals and continues to sit in [a] busy criminal part in Queens County Supreme Court, a court that is at the forefront of the statewide reduction in case backlogs and trial delays,” Chalfen said.

In a response for an answer to the specific question of the court system's ability to hold judge's accountable, Chalfen said that judges have wide latitude and discretion in their courts.

“Remedies to their decisions are the appellate process—that have been used in these instances,” he said. “And judges do heed the rulings of those decisions.”

Related:

Panel Again Reverses Conviction, Citing Proof of Uncharged Crime

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Haynes and Boone Expands in New York With 7-Lawyer Seward & Kissel Fund Finance, Securitization Team

3 minute read

Ticket-Fixing Scheme Results in Western NY Judge's Resignation—for a Second Time

Disbarred NY Atty Receives 54-Month Prison Sentence After $3M Embezzlement

3 minute read

Legal Community Mourns the Loss of Trailblazing Judge Dorothy Chin Brandt

Trending Stories

- 1Munger, Gibson Dunn Billed $63 Million to Snap in 2024

- 2January Petitions Press High Court on Guns, Birth Certificate Sex Classifications

- 3'A Waste of Your Time': Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

- 4Judge Extends Tom Girardi's Time in Prison Medical Facility to Feb. 20

- 5Supreme Court Denies Trump's Request to Pause Pending Environmental Cases

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250