Justice O'Connor's Diagnosis Is a Reminder That Lawyers Can't Ignore Dementia

As a rising tide of Alzheimer's and other dementia diagnoses grips aging law firm partnerships, neither firms nor their lawyers have learned how to cope.

October 24, 2018 at 10:55 AM

19 minute read

The original version of this story was published on The American Lawyer

Illustration by Raul Arias. Motion Graphic by Hyeon Jin Kim

Editor's note: On Tuesday morning, retired Justice Sandra Day O'Connor revealed that she has been diagnosed with early-stage dementia. In light of this news, we are republishing this story from the March issue of The American Lawyer about lawyers and law firms' inability to cope with the effects of dementia—and the harm that can befall those who ignore it.

Before Myriam Marquez was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, she had a full-time practice as a public defender near Seattle. As her office's only Spanish-speaking public defender, she juggled up to 20 cases at one time.

One day Marquez couldn't remember how to drive home from the office. By 2010, at age 63, genetic testing had confirmed that she carried a gene for Alzheimer's disease. She knew she had to tell her boss.

“He said, 'Oh no, you can't work here anymore, you're a liability',” says Marquez, a onetime adjunct professor at Georgetown University Law Center.

His words, Marquez says, show the stigma—and the consequences—that Alzheimer's carries in the legal business. One of her own family members, also a lawyer with Alzheimer's, has refused to publicly reveal the illness, she says, as have some of Marquez's closest friends.

“A lot of them don't want anyone to know, they feel it's a shameful thing,” she says. “They're afraid of telling anyone.”

Despite the growing public awareness and advocacy to help lawyers confront addiction, depression and other mental health diseases, very few are willing to share their stories about Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia.

“We have lawyers who have substance abuse issues, who find recovery, they get better, and they're willing to share their story to give other people hope—that you too can recover,” says Terry Harrell, executive director of the Indiana Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program and former chair of the American Bar Association's Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP). “But with dementia, unfortunately, all we know is it is only going to get worse.”

The problem also promises to get worse for the legal industry.

As the baby boomers enter their 70s and attorneys live and work longer, examples have proliferated of lawyers—including prominent Big Law partners—retreating from their practices due to dementia and Alzheimer's, though none of the lawyers or their family members contacted for this story were willing to be identified. Several chief talent officers at Am Law 200 firms also declined to discuss the issue.

“Every major law firm,” says Michael Ross, a Manhattan lawyer often representing lawyers and firms in ethical and discipline matters, “is dealing with this because they have lawyers who are graying.”

At the same time, many experts say the firms are woefully unprepared. “From what I've seen, law firms of all sizes have done a very poor job of planning for what is an inevitable circumstance,” says Bree Buchanan, current chair of the ABA's LAP commission and director of the Texas Lawyers Assistance Program of the state bar of Texas.

The lawyers themselves may be unwilling to acknowledge their diagnosis, sparking ethical concerns, or may even be too impaired to assess their own abilities. Too often, say Buchanan and others, their colleagues are reluctant to bring issues to management's attention—risking economic and liability concerns, harm to the clients and any chance for a graceful exit.

The Numbers

While the demographics of dementia won't spare any industry, law firms face special challenges given the importance of senior partners to their business.

“With the reduction in mandatory retirement policies in law firms, the range of senior lawyers' ages in full-time practice and lengths of phase-down intervals are increasing,” with more seniors practicing into their late 60s and 70s, says Alan Olson, a law firm consultant at Altman Weil Inc. “Profession-wide, this increases the possibility that some lawyers might continue to practice with diminishing skills.”

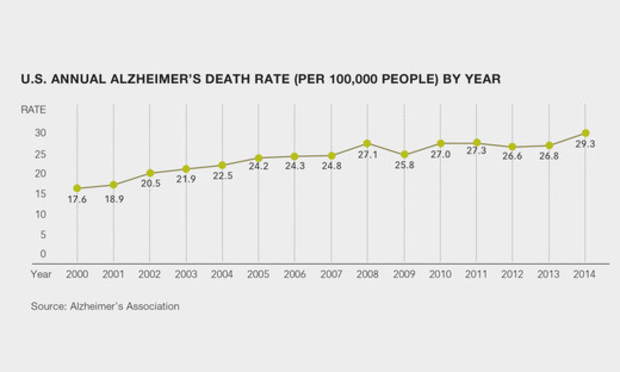

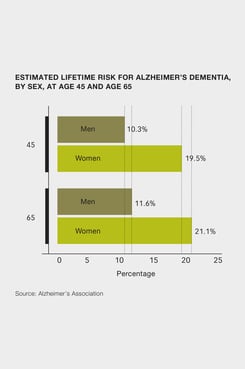

In 2011, the baby boomer generation began to reach age 65 and beyond—the age range when the risk of Alzheimer's is greatest, according to the Alzheimer's Association. One in 10 people age 65 and older has Alzheimer's dementia, the group says, and by 2025, the number of Alzheimer's sufferers in that cohort is estimated to reach 7.1 million—almost a 35 percent increase from the 5.3 million Americans over 65 who were affected in 2017.

Some who work on the front lines helping attorneys with mental health and impairment issues, particularly at lawyer assistance programs, are watching that wave take shape. LAPs were established in the 1980s to help lawyers with alcohol abuse, Buchanan says, but they are increasingly addressing a range of impairment issues, including forms of dementia.

In 2016, about 4.1 percent of the issues that LAPs addressed across the county involved cognitive issues and aging, according to preliminary data from a comprehensive LAP survey by the ABA commission. That appears to be an increase from 2014, when LAPs reported 2.8 percent of the issues they saw were for cognitive issue and aging.

“When you have a greater percentage of the professional population begin to comprise senior lawyers, then it's naturally going to follow you are going to start to see a rise in some cognitive impairment,” says Buchanan, who is also co-chair of the National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being.

At the Texas LAP, Buchanan says she is getting more calls about cognitive impairment, including calls from lawyers, colleagues, judges, clients and family members concerned about a lawyer showing memory and judgment mistakes.

At the Texas LAP, Buchanan says she is getting more calls about cognitive impairment, including calls from lawyers, colleagues, judges, clients and family members concerned about a lawyer showing memory and judgment mistakes.

Since the trend began about five or six years ago, Buchanan says she gets up to 10 such calls a year now in Texas. “It's not overwhelming but it's an increase,” she says, noting other LAPs are also seeing a rise in such calls. “This is an emerging issue for LAPs across the country.”

Eileen Travis, director of the New York City Bar Association's Lawyer Assistance Program, says she has seen a rise in calls from lawyers trying to balance their work demands while caring for a spouse or parent who has dementia.

Ross, the lawyer who counsels firms on ethics issues, says he has begun to help clients confront dementia-related issues at least a few times a year. In the 1980s, it was rare to get such a request, he notes, adding, “Now it's not unusual.”

'A Devastating Moment'

Dr. Doris Gundersen, a psychiatrist and medical director of Colorado Physician Health Program, says attorneys possess something called high cognitive reserve—a trait they share with physicians and others with high levels of education. “Even with some cognitive changes, an attorney may be able to function longer than somebody who doesn't have that reserve,” Gundersen says.

One result is that a diagnosis for lawyers and other highly educated people can be delayed, says Dr. Davangere Devanand, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center who studies Alzheimer's disease and geriatric depression. They may have a diagnosis several months to a few years later than someone else, even though they have the same disease because they can compensate for it, he notes. “Clinically they look like its early to moderate, but based on all the brain imaging it usually looks like it's advanced a little more in the brain,” Devanand says. “Their brains have a way to work away the problem.”

Early in Alzheimer's, some of the most common signs are financial errors and mistakes, Devanand says, as well as short-term memory declines.

“Long-term memory tends to be preserved, but over time as the illness progresses, unfortunately, a lot of function is lost, including basic activities of daily living,” with advanced dementia, Gundersen says.

Gundersen says an attorney's colleagues could notice a real change in competency: demonstrating poor judgment, missing deadlines, being forgetful and relying more on support staff for things they would typically do independently.

The changes could also extend to appearance, says Patrick Krill, a consultant to law firms on mental health, addiction and impairment issues. Krill says colleagues may notice changes in dress and hygiene, as well as personality. “Maybe some level of disinhibition, not exhibiting the same level of decorum, professionalism or cordiality, and their personality could just seem off,” Krill says.

Gundersen and others caution that similar symptoms could stem from other, much more treatable illnesses, such as depression, addiction and various reversible medical conditions.

A lawyer with dementia often doesn't seek medical advice on his or her own, Gundersen says. Attorneys are commonly referred to her by a colleague, family member or assistance program, or after being investigated by a regulatory agency, she says.

Gundersen says her patients undergo a neuropsychological evaluation that can examine specific areas of deficiency and identify dementia. “If that's established, the professional really needs a lot of support as they being to exit their professional lives. It's quite a devastating moment in time,” she says.

Even with a professional diagnosis, “there can be some denial” when a lawyer is diagnosed, Gundersen says.

“Their primary tool is their cognitive excellence, so there's a grieving process and it can be accompanied by clinical depression and suicidal thoughts,” she says. “You try to identify what strengths they have and get them involved in activities that they can still perform, make sure they have community support and they're socially connected to avoid social isolation.”

Gundersen herself recommends cognitive screening at age 75, noting it's in the eighth decade of life that cognitive impairment is more likely and noticeable. “The older we get, the more likely we all get dementia,” she says.

Firms Delay Action

When there is a diagnosis, a tendency among both lawyers and their firms to delay taking action can often make matters worse. Sometimes even family members don't raise alarm bells, because they may want the person to keep working for personal or financial reasons, Devanand says.

“The preferred path of many lawyers is to ignore it for as long as possible, to turn a blind eye on the trouble and hope it goes away. If the lawyer continues to deteriorate, you'll likely to have harm done to the lawyer and the clients,” Buchanan says. “Lawyers show up in court, they don't know what case they're on, they start a trial and they can't remember who their client is and they can't remember the fact scenario.”

“Even though we like these cases to be handled by LAPs,” she says, “what more often happens is, if [there's no intervention or help], the disciplinary authority becomes involved.” Lawyers assistance programs, she says, “can't take away a person's license to practice and sometimes that's simply what it takes to get a lawyer to step away from their practice.”

For a senior lawyer who has established a client base and has generated significant goodwill, “there can be a level of deference shown,” says Krill. But, he adds, sometimes “people are extended the benefit of the doubt beyond what is ideal.”

Firms often won't take any action until there are direct complaints from other lawyers, or even from clients, Krill says. Frequently for firm management, he says, “There's some reluctance, some heated debate about whether he or she has a problem. They can spin their wheels for a long time, and there can be an overanalysis happening and the problem can go unaddressed for a long time.”

Buchanan says a majority of large law firms treat dementia diagnoses as individual emergencies and don't have a plan in place for transitioning lawyers with cognitive impairment. “This is pretty cutting edge for law firms to have those policies or plans in place ahead of time,” she says.

Krill agrees that firms are not nearly as a proactive as they should be. “There's sometimes institutional denial that the problems … exist, there's a reluctance to deal with these problems and it's been that way for a very long time,” Krill says.

While Harrell, at the Indiana LAP, says colleagues are sometimes reluctant to force their partner to retire, “the flip side is the earlier you can intervene, the easier it can be to get the person to cooperate” through a retirement or by reducing his or her practice with supervision. “If you wait too late and someone has significant dementia, they've lost insight on their own behavior. We've had a couple lawyers where dementia was so advanced, that they were no longer capable of making logical decisions in their own best interest,” Harrell says.

Ethics and Liability

For firms, the risks extend to economic and liability consequences. Dan Donnelly, senior vice president of claims at ALAS, a malpractice insurance carrier to many Am Law 200 firms, says there have been times “when a claim emerges and everyone looks back” to a lawyer's behavior three to five years ago, when he or she may have had dementia.

Donnelly recalled one example when a lawyer who represented a charitable organization in negotiating a gift also represented the donor of the gift. Years later, he says, it became clear that the person already had dementia when entering into the conflict.

Donnelly has also seen about a half-dozen cases when lawyers who would be critical witnesses to the defense of a malpractice claim are incapacitated and have no reliable memory of events. “While you hope there is a documentary track record, oftentimes it does come down to testimony from lawyers, that 'I did advise the client that he or she should do this or should not do this',” Donnelly says. “And when the lawyer who rendered the advice is incapacitated, it makes it more challenging.”

Firms don't have to notify ALAS about an attorney with Alzheimer's or dementia unless they think there's an actual event of liability or a client was harmed, says Robert Denby, the company's senior vice president of loss prevention.

Many firms keep their lawyers' past and current dementia diagnoses secret out of fear of malpractice claims or ineffective assistance of counsel complaints, no matter how frivolous, according to industry observers.

While malpractice liability should drive law firms to quickly address the issue, it's also an ethical duty. Under ABA model rules, a firm should make reasonable efforts to make sure all lawyers in the firm conform to professional rules of responsibility, and a lawyer who has management or supervision responsibility should take steps to make sure employees are complying with the rules.

Impaired lawyers have the same obligations under the model rules as other lawyers, and a lawyer who believes that another lawyer's known violations of disciplinary rules raise substantial questions about her fitness to practice must report them, according to ABA ethics opinions.

Lawyers themselves cannot meet the professional rules if they are not diligent and competent, says Ross, who said he would rate the profession much better in recognizing and addressing the issue than a couple decades ago. “The economics and the ethics are driving us to do a better job,” he says. “If you're in a law firm and you disregard that risk,” Ross says, “it would be the same thing as disregarding your partner stealing.”

'Clumsy and Awkward'

As if worries about potential malpractice claims weren't enough, firms also face employment law considerations involving various disability and privacy statutes.

Typically, a firm leader will approach the lawyer showing impairment issues in what is “often a very clumsy and awkward conversation,” Krill says. “I've been involved in situations where the lawyer in question will ultimately be very cooperative and I've been involved in situations where the lawyer has told the firm to get lost. The response can range anywhere from full cooperation to complete defiance.”

Very often in larger firms, Ross says, a firm will also contact a family member and “want to test the water with a family member in a healthy and positive way and ask the question, 'Do you see John or Jane having challenges or problems with remembering or performing?'”

Sometimes the family will act defensively, because they don't want to interrupt an income source. But very often they will say “'I know what you're talking about and I think we may have an issue here,' and oftentimes there's a collaboration between family and firm,” Ross says.

Upon a diagnosis, “when a lawyer realizes their career is at endgame, my experience is that they're not going to go kicking and screaming,” Ross says, adding they are often respectful of the firm and clients.

The attorney doesn't have to stop practicing completely. Sometimes lawyers with a cognitive impairment diagnosis will shift their practice to be less in court, Ross says. “They may continue practicing but in a different capacity,” such as mentoring other lawyers, he notes.

Denby says he has seen some firms require that a lawyer no longer bill client work, but may lend their name or give speeches.

Sometimes firms will take an intermediate step, ensuring another lawyer is on every file if the lawyer is still involved in client matters, Denby says. “As long as the firm is actively monitoring the situation and adjusting as the situation changes, we're OK with that,” Denby adds.

When firm leaders learn of a potential cognitive impairment, Denby recommends they delegate a lawyer, such as the firm's general counsel, to investigate—including potentially reviewing past client work.

If there's a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, “an attorney can continue practicing for a while with some accommodations” and supervision, says Gundersen, who is on the character and fitness committee of the Colorado Board of Law Examiners. “Some people progress rapidly over a matter of months, and for others it may be years,” she says.

If detected early, firms will likely make a transition plan to move matters to another attorney over a period of time and to assign another attorney to review current files, Denby says. If firms respond right away, such as removing the attorney from billing matters or assigning a shadow on all matters, “I think it's fairly effective in avoiding malpractice problems,” Denby says.

However, firms face the risk when the attorney is a heavy rainmaker “who doesn't want to give up the reins,” Denby says. “The fundamental practice risk is they may let that person practice without supervision too long,” he says.

Marquez, the former Seattle public defender with Alzheimer's, says after her boss told her she had to quit, human resources officials called her back and urged her to stay. Still, she decided to leave within weeks. She regrets leaving so soon, she says, knowing she's had many productive years since.

“There's a lot of differences” between one person with dementia and the next, Marquez says.

What's Next

The ABA has become more active in publicizing the signs and symptoms of cognitive decline for LAPs and others, and various bar associations now organize webinars and conferences to raise awareness. LAPs across the country can educate lawyers about warning signs and how to proceed after a diagnosis.

“We're coming from no systemized approach, so there was a lot of variability across states and law firms,” says Gundersen. “Now there's an education process of utilizing LAPs more to make sure the intervention goes smoothly and the individual gets the help they need.”

“We're in the early stages of changing the culture of law to recognize attorneys are human first, not immune to illness,” she says.

One major challenge is that there is still no widely disseminated model policy for law firms to look to for guidance. The last model policy on lawyer impairment was issued in 1990, and it was focused on helping lawyers experiencing alcoholism, Buchanan says.

The current ABA president, Hilarie Bass, co-president of Greenberg Traurig, has created a working group on lawyer well-being. The group is developing new model law firm policies, which could be released this spring, on recognizing and addressing issues related to impairments, including cognitive, mental health and substance abuse disorders. The guidance would cover how firms report and investigate problems, handling LAP referrals, confidentiality, lawyer and law firm obligations and employment considerations, says Buchanan, who is on the working group.

“We hope that the policy that emerges from the working group is something that we would be happy to recommend to our firms,” says ALAS's Denby, who is also part of the working group.

For now, a few firms are trying to create plans on their own to recognize warning signs in lawyers, whether they signal dementia, mental health or other issues.

Susan Manch, chief talent officer at Winston & Strawn, says law firms need to be more proactive. Manch, who joined Winston last year from Norton Rose Fulbright, and another Winston leader, Julia Mercier, the firm's director of learning and development, are trained and certified as mental health first responders to recognize signs of cognitive distress or impairment in lawyers and staff. This year, the pair will help launch a firm program to train employees, including human resources personnel, to recognize the warning signs and to be available as a resource.

“We need to make sure from an HR perspective that we're providing world-class benefits so we have the resources there to make sure people are courageous enough to come forward,” says Manch, who started a similar program at her last firm. “Every law firm can do better.”

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Family Law Practitioners Weigh In on Court System's New Joint Divorce Program

Former NY City Hall Official Tied to Adams Corruption Probe to Plead Guilty

New Charges Expected in Sex Trafficking Case Against Broker Brothers

Trending Stories

- 1'Shame on Us': Lawyer Hits Hard After Judge's Suicide

- 2Upholding the Integrity of the Rule of Law Amid Trump 2.0

- 3Connecticut Movers: New Laterals, Expanding Teams

- 4Eliminating Judicial Exceptions: The Promise of the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act

- 5AI in Legal: Disruptive Potential and Practical Realities

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250