Arbitration: New Limits on the Horizon?

The current term sees the court facing a set of cases which focus on the types of claims that can be litigated in arbitration and the relative powers of arbitrators and judges. In three cases that already have been argued, the court may limit the scope and authority of arbitrators.

November 09, 2018 at 03:40 PM

9 minute read

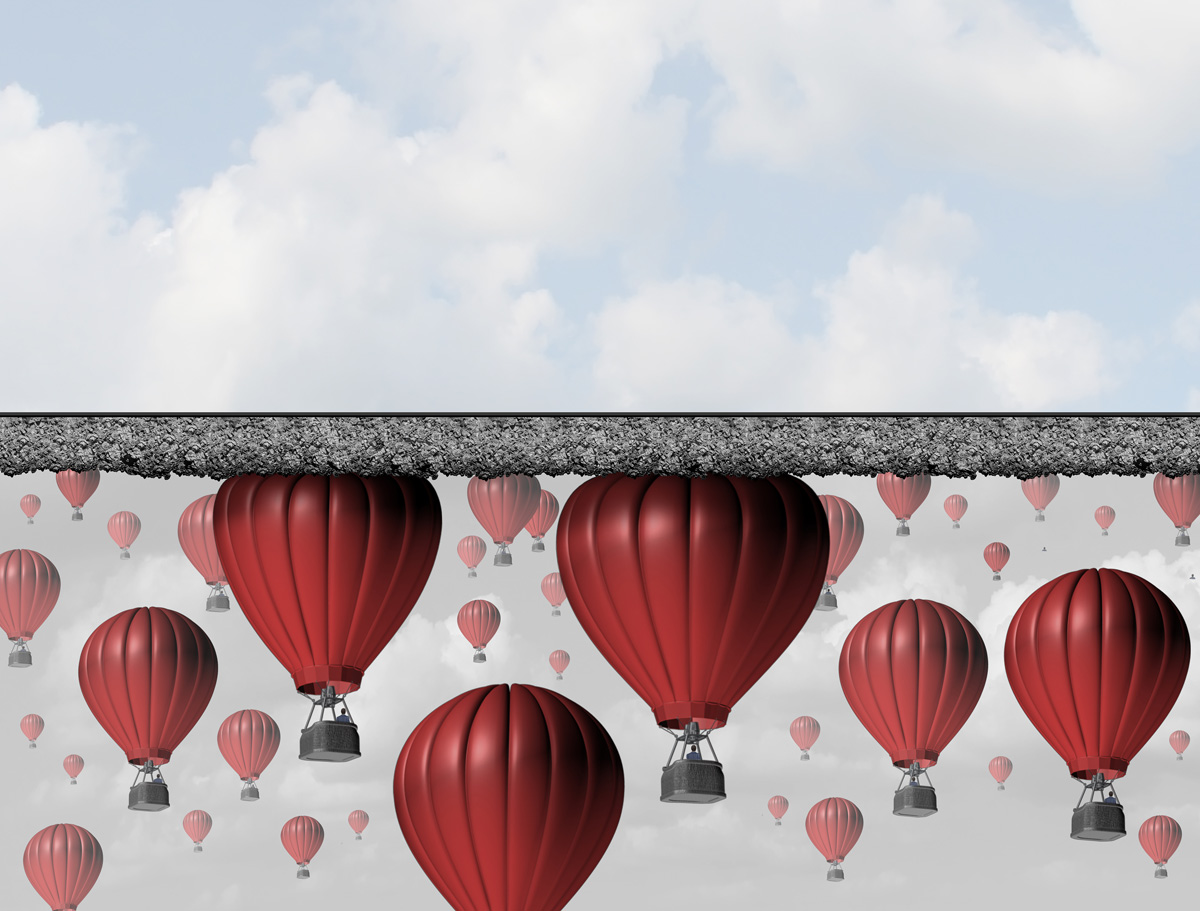

One of the first issues litigators often confront is whether the case will proceed in a judicial or arbitral forum. Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has provided strong support for arbitration, most recently enforcing arbitration clauses that prevent plaintiffs from bringing class actions. The current term, however, sees the court facing a new set of cases, which focus on the types of claims that can be litigated in arbitration and the relative powers of arbitrators and judges. In three cases that already have been argued, the court may limit the scope and authority of arbitrators.

One of the first issues litigators often confront is whether the case will proceed in a judicial or arbitral forum. Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has provided strong support for arbitration, most recently enforcing arbitration clauses that prevent plaintiffs from bringing class actions. The current term, however, sees the court facing a new set of cases, which focus on the types of claims that can be litigated in arbitration and the relative powers of arbitrators and judges. In three cases that already have been argued, the court may limit the scope and authority of arbitrators.

Of greatest interest is Lamps Plus v. Varela, No. 17-988, in which the court is considering whether arbitration under the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) may include class arbitration. Lamps Plus arises out of an employment agreement to arbitrate that contained no specific mention of class arbitration. The Ninth Circuit held that the absence of such language does not determine whether the arbitration agreement could be interpreted to permit class arbitration. Relying on California contract law, it concluded that the agreement was susceptible to an interpretation that authorized class arbitration. It then interpreted the agreement against the drafter—the employer—and held that class arbitration was permitted.

The petitioners raise a host of arguments specific to the contract, but also advance a broader rule that class arbitration is incompatible with the FAA. Relying on AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011), the first decision that upheld class action waivers, the petitioners maintain that class arbitration requires an express agreement and cannot be permitted by implication. Arbitration is fundamentally a matter of bilateral agreement between the contracting parties, which is inconsistent with expanding an arbitration to decide the claims of an entire class. Moreover, petitioners argue that class arbitration contravenes the purpose of arbitration—to furnish a less expensive and informal alternative to litigation in civil courts.

Oral argument in the case provided no clear signals as to what the court is likely to hold. Justices Elena Kagan, Brett Kavanaugh, and Neil Gorsuch sought a textual basis in the FAA for precluding class arbitration, though Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Samuel Alito, expressed concerns about due process should an arbitration seek to adjudicate the claims of parties that never signed arbitration agreements. Chief Justice John Roberts questioned whether state law principles should govern if they impose a procedure—class arbitration—that is like “a poison pill” to defendants.

Other Justices focused on a procedural question. Because the district court ordered the matter to arbitration and dismissed the case, the arbitration order was part of an appealable final judgment. Yet when a district court stays proceedings pending arbitration, the arbitration order is not appealable. Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Sonia Sotomayor questioned whether trial courts should have the power to make an arbitration order appealable by dismissing rather than staying such a case.

Given these questions, Lamps Plus may result in a plurality decision, with no clear consensus emerging on whether the FAA bars class arbitration. However, if the court does reach the issue and finds class arbitration impermissible under the FAA, it could result in a sea change in modern litigation. Given the widespread use of arbitration agreements in employment agreements and consumer transactions, Lamps Plus could effectively eliminate employment and consumer class litigation in arbitrations.

The court also will decide two other arbitration-related cases this term. Both deal with the authority of courts and arbitrators to decide issues of arbitrability.

New Prime v. Oliveira, No. 17-340, raises two questions: (1) whether the exemption under the FAA for “contracts of employment of seamen, railroad employees, or any other class of workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce” (9 U.S.C. §1) applies to truck drivers working as independent contractors; and (2) whether the application of that exemption can be decided by a court or if it must be decided by an arbitrator when the agreement delegates questions of arbitrability to the arbitrator. A panel of the First Circuit unanimously held that a court may decide if the exemption applies and split 2-1 in holding that the exemption applies to independent contractors.

At oral argument, the Justices strongly indicated that they will affirm the First Circuit's decision. Several Justices, including Justices Ginsburg, Gorsuch, and Roberts, appeared skeptical that the FAA permits arbitration of a claim that might be exempt from the statute's scope. A district court must first decide if the FAA applies to a claim before it has the power to order any issue to arbitration, including the arbitrability of the claims. As Justice Ginsburg pointed out, if the claims fall outside the scope of the FAA, “you can't use the Act to enforce any arbitration.” Chief Justice Roberts added that, while certain issues of arbitrability “within the four corners of the arbitration agreement” are legitimately issues for the arbitrator to decide, the issue of whether the FAA applies at all “seems to be on a different order of magnitude.”

On the issue of the exemption itself, the court appears likely to hold that the exemption applies to independent contractors, because the statute's exemption applies to “contracts of employment of … workers[,]” not just to contracts of “employees.” The Justices seemed dubious about the employer's argument that only employees are subject to “contracts of employment.” For instance, Chief Justice Roberts pointed out that “[p]eople think naturally of employing an independent contractor.”

The decision in New Prime may determine how the court approaches the remaining arbitration case. As in New Prime, the question in Henry Schein v. Archer and White Sales, No. 17-340, turns on whether a question of arbitrability must be submitted to an arbitrator. Unlike New Prime, however, the question does not turn on the scope of the FAA and whether a court has power under the statute to order a claim to arbitration.

Henry Schein instead involves a two-part test adopted by the Fifth Circuit in Douglas v. Regions Bank, 757 F.3d 460 (5th Cir. 2014), to decide if a claim is arbitrable: (1) whether the parties had a clear and unmistakable agreement to arbitrate the claims at issue unless (2) “the argument that the claim at hand is within the scope of the arbitration agreement is 'wholly groundless.'” Id. at 464. Other Circuits similarly have adopted tests that permit district courts to decline to order arbitration of claims that clearly fall outside the contracted scope of arbitration. E.g., Turi v. Main St. Adoption Servs., 633 F.3d 496, 507 (6th Cir. 2011); Qualcomm v. Nokia, 466 F.3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

In Henry Schein, the Fifth Circuit did not decide whether the parties had demonstrated the requisite intent to delegate arbitrability, but held that the arbitration demand was “wholly groundless.” The plaintiff had sought damages and injunctive relief against the defendants. When the defendants moved to compel arbitration, the plaintiff opposed on the grounds that the arbitration agreement exempted “actions seeking injunctive relief … .” Siding with the plaintiff, the Fifth Circuit held that the arbitration demand was “wholly groundless” because the claim included a demand for injunctive relief.

At the Supreme Court, the defendants argue that, when the parties delegate the issue of arbitrability, a district court has no authority to consider whether the claim falls outside the scope of the agreement; only the arbitrator can decide that. The plaintiff argues that parties do not contract to send implausible or illegitimate demands to arbitration and doing so for threshold determinations of arbitrability of clearly non-arbitrable claims is inconsistent with the FAA's objectives. The plaintiff also argues that, because a court can vacate an award if it finds the arbitrator exceeded its powers by deciding a claim that was not arbitrable, it defies common sense to hold that the court has no power to do the same before arbitration.

Surprisingly, the plaintiff has not raised an argument that might complement the likely ruling in New Prime. Just as the court seems receptive to the argument that a trial court has no power to order a claim to arbitration if it lacks the statutory authority to do so, an analogous argument could have been made that, because arbitration is a matter of contract, if the parties have contractually exempted certain claims, the district court has no authority to order those claims to arbitration even for the purpose of deciding the scope of arbitrability.

At the recent oral argument, Justices Ginsburg and Breyer seemed to consider this issue, but not as part of the test for whether a claim was “wholly groundless.” Instead, citing an amicus brief written by Prof. George Berman, they indicated that a court might consider if the claim was actually something the parties had clearly and unmistakably agreed to arbitrate, the first prong of the Fifth Circuit's test.

As for the “wholly groundless” prong, the Court as a whole seemed fairly dubious about adopting it. Several Justices appeared to view that standard as intruding into the merits of the claim, while others struggled to identify the types of arguments that would be asserted if litigants could contest arbitration demands using a “wholly groundless” standard.

Together, New Prime and Henry Schein could change how parties litigate arbitrability and whether they reconsider delegating questions of arbitrability to arbitrators.

Rex S. Heinke is a partner and co-head of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld's Supreme Court and Appellate practice. Jessica M. Weisel is senior counsel in the firm's litigation practice. Douglass B. Maynard is partner and general counsel of the firm.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

- 1In Novel Oil and Gas Feud, 5th Circuit Gives Choice of Arbitration Venue

- 2Jury Seated in Glynn County Trial of Ex-Prosecutor Accused of Shielding Ahmaud Arbery's Killers

- 3Ex-Archegos CFO Gets 8-Year Prison Sentence for Fraud Scheme

- 4Judges Split Over Whether Indigent Prisoners Bringing Suit Must Each Pay Filing Fee

- 5Law Firms Report Wide Growth, Successful Billing Rate Increases and Less Merger Interest

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250