After Fall From Grace, David Boies Plots Next Battle

For the 77-year-old litigator, 2018 was not a very good year. And if (to quote the old Frank Sinatra song), Boies thinks of his life “as vintage wine from fine old kegs, from the brim to the dregs...” Well, this is probably the dregs.

November 15, 2018 at 11:17 AM

8 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Law.com

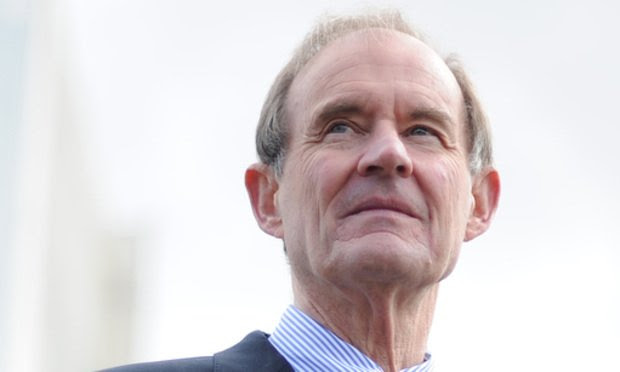

David Boies. Photo by Diego Radzinschi.

David Boies. Photo by Diego Radzinschi.

The day is chilly and gray—San Francisco at its worst, the air heavy with drift smoke from an inferno raging 180 miles to the northeast.

In the plush lobby bar of the Ritz Carlton atop Nob Hill, David Boies kicks off a recent interview at sunset with an old joke: Mark Twain said the coldest winter he ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.

Except it's November.

In town for a memorial service and a meeting with lawyers in Boies Schiller Flexner's Oakland office across the San Francisco Bay, Boies has also been to visit his Northern California winery, Hawk and Horse, in Lake County.

The harvest is a total loss. The delicate flavors of the unpicked grapes were ruined by smoke from California's devastating wildfires.

But Boies is sanguine as he orders a Ketel One vodka with fresh-squeezed orange juice. Last year's harvest was abundant, and so was the year before. There's plenty of inventory in the barrels.

It's a fitting metaphor. Because for the 77-year-old litigator, 2018 was not a very good year. And if (to quote the old Frank Sinatra song), Boies thinks of his life “as vintage wine from fine old kegs, from the brim to the dregs…” Well, this is probably the dregs.

Even as he looks ahead to what could be his biggest case of all—reforming the Electoral College—and ensures that his firm is well-positioned to thrive when he and the other name partners eventually retire, Boies has also endured stinging criticism for his work on behalf of Harvey Weinstein and failed blood testing company Theranos.

Even as he looks ahead to what could be his biggest case of all—reforming the Electoral College—and ensures that his firm is well-positioned to thrive when he and the other name partners eventually retire, Boies has also endured stinging criticism for his work on behalf of Harvey Weinstein and failed blood testing company Theranos.

“The last 12 months have been an unprecedented public relations disaster for the most prominent lawyer in America,” wrote New York Times reporter James Stewart in a lengthy profile in September. “For the first time in his career, the most vaunted advocate in the United States has been a defendant in the court of public opinion.”

Boies said he thought Stewart's piece was fair. And considering that litigators, (in my experience) tend to reflexively argue that whatever they do is right, he seems surprisingly philosophical about what some have called his fall from grace.

He didn't even take the bait when I offered him an easy avenue for self-justification. That is, Boies has put in major pro bono hours in recent years to go after website Backpage for sex trafficking, and to represent women who say they were sexually abused as teens by billionaire Jeffrey Epstein. Shouldn't that work be taken into account too?

“If there is legitimate criticism for representing Harvey Weinstein,” Boies said, “I don't think the fact that I've done these other cases means I shouldn't be criticized.”

But he does note that when he first began representing Weinstein, the film producer was highly regarded and honored within the entertainment industry.

“I do believe lawyers have substantial discretion as to what clients they take on,” Boies said.

But once you're on board? You can't just walk away at the first sign of trouble.

“When allegations are made against a client, and he denies the allegations, I don't believe lawyers should lightly abandon the client just because he's accused of conduct he denies,” Boies said. “When you represent a client, you have an obligation to that client to represent them zealously.”

It's been a hallmark of his career, from his start at Cravath, Swaine & Moore to his work on behalf of clients, including the Justice Department in litigating the Microsoft antitrust case, Vice President Al Gore in Bush v. Gore, and in tandem with Ted Olson in fighting California's ban on same-sex marriage.

In part, Boies credits his gift for extemporaneous speaking to his dyslexia. “I'll work things through orally, as opposed to reading,” he said. “I spend a lot of time talking to people in preparation. … I'll sit with people, all kinds of people, anyone I can find.”

Can being a litigator be taught? How much is art, and how much craft? “An excellent question,” he says. “You can teach some, but you've got to have the raw material to work with.”

Often he can just tell who has the gift. When he first met Jonathan Schiller, for example, Boies said he knew right away that he wanted to work with him. The same goes for other firm stars such as Bill Isaacson, Natasha Harrison, Karen Dyer, Karen Dunn, Quyen Ta and more.

It's evident he takes considerable pride in the younger generation of talent at 320-lawyer Boies Schiller.

So what's his response to recent remarks by Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan co-founder John Quinn, who said he has little use for succession planning?

“We're the exact opposite,” Boies said. “We've been planning succession for 15 years.”

That was when Boies, Schiller and Donald Flexner realized that the three of them accounted for 90 percent to 95 percent of the firm's business. For the institution to live on, they knew they needed to start a gradual transition.

There are three elements, Boies said: recruit and retain first-rate people; support their efforts at generating new business and establishing relationships with existing clients; and hand over more firm governance to the administrative partners who oversee operations at each of the firm's 15 offices.

If he retired tomorrow, Boies said, “the firm would be in good shape.” But he added, “I think I still have some things to contribute.”

He's got a trial in Los Angeles starting Dec. 4—fight over a painting by Camille Pissarro that was allegedly looted by the Nazis and is now in a Spanish state-owned museum. Boies represents the descendants of the original owner, a German Jew, who want the art returned.

He's also on standby in the event that Florida Sen. Bill Nelson's recount turns into a full-on litigation, a little bit of déjà vu, circa 2000. (On the plus side, Florida changed its ballots and no longer has hanging chads.)

But the biggest fight on his horizon is reforming the Electoral College.

Harvard Law School professor Lawrence Lessig founded the nonprofit Equal Citizens, and recruited Boies to serve as lead counsel in challenging the winner-take-all system of allocating Electoral College votes.

Working pro bono, Boies has teamed up with Lessig and Equal Citizens lawyer Jason Harrow, along with eight partner firms, including Alston & Bird; Steptoe & Johnson LLP; and Hausfeld, plus law school profs Richard Painter, Sam Isaacharoff and Guy-Uriel Charles.

They've filed suits in California and Massachusetts on behalf of Republican voters, and in Texas and South Carolina on behalf of Democrats.

Every state but Maine and Nebraska awards all of its electoral votes to the statewide winner. That means, for example, that while 4,483,810 Californians voted for Donald Trump, this translated into zero Electoral College votes, according to the Equal Votes website. Likewise, 3,868,291 Texans voted for Hillary Clinton, but that too translated into zero Electoral College votes.

“To be clear, this lawsuit is not a challenge to the Electoral College, which is mandated by the Constitution,” the complaints state. “The Constitution does not address how states should select Electors, and it certainly does not require [winner-take-all]. To the contrary, as shown below, WTA is inimical to the long-established principle of 'one person, one vote,' and thereby violates the fundamental constitutional right to vote, as well as other constitutional rights.”

It's a compelling argument, but Boies acknowledges it will be a difficult battle. “We're fighting precedent,” he said.

The point isn't just to make those four states change their practices, but to win a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court on constitutional grounds that would apply nationwide.

Boies believes that if they are successful, it will strengthen our country and better align presidential elections to the will of the people.

“It's part of our constitutional scheme that every vote counts,” he said. “Making democracy work is in my view the core role of the courts in our society.”

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Litigation Daily, the exclusive source for sharp commentary on mega court battles, winning strategies and the issues that obsess elite litigators. Click here to subscribe.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

‘Catholic Charities v. Wisconsin Labor and Industry Review Commission’: Another Consequence of 'Hobby Lobby'?

8 minute read

AI and Social Media Fakes: Are You Protecting Your Brand?

Neighboring States Have Either Passed or Proposed Climate Superfund Laws—Is Pennsylvania Next?

7 minute read

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250