DiFiore Presses Appellate Judges to Send Fewer Appeals to High Court

Citing a desire for the Court of Appeals to control its own docket, Chief Judge Janet DiFiore has made clear her desire to see a more restrained appeal process from the lower courts, according to numerous current and former appellate justices.

November 26, 2018 at 11:00 AM

8 minute read

Chief Judge Janet DiFiore hears arguments at the Court of Appeals in 2016. (Photo: Tim Roske)

Chief Judge Janet DiFiore hears arguments at the Court of Appeals in 2016. (Photo: Tim Roske)

New York Court of Appeals Chief Judge Janet DiFiore has discouraged justices in the Supreme Court's appellate departments from sending cases to the high court in a dramatic departure from her predecessor's practice.

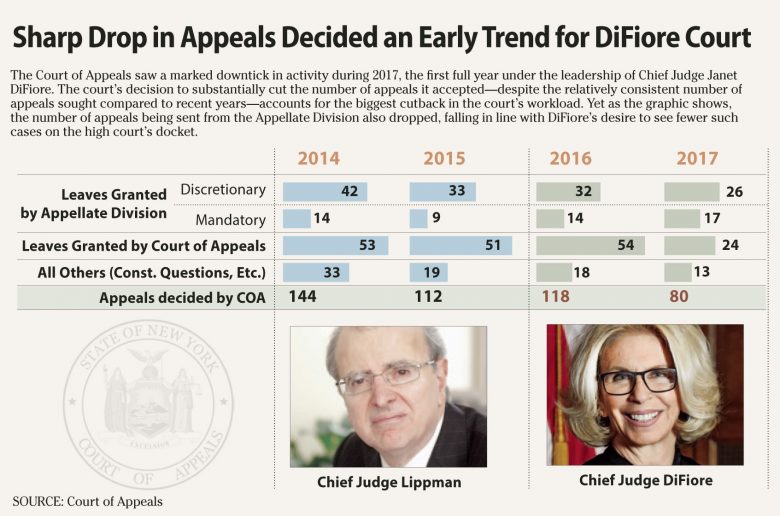

DiFiore demonstrated her intent to control her court's docket—realized in 2017 with a sharp decline in the number of appeals heard—early in her tenure as chief judge.

In June 2016, the justices of the First Department gathered in the dining room of its ornate Madison Avenue courthouse. They were set for their weekly lunch meeting before the 2:15 p.m. status conference, an event that often draws a guest speaker.

On that day, the guest speaker was DiFiore. It was her first visit to the court since her confirmation by the state Senate in late January.

The judges had a lot of questions for the chief judge, but one line of inquiry carried a little more weight: How do you feel about us sending cases to the high court? Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman had welcomed appeals. The more, the better was his position. DiFiore disagreed.

“She made it clear that they want to choose what they should hear. They don't want us deciding what goes onto their calendar,” one of the judges recalled.

DiFiore's answer wasn't an off-the-cuff remark. Several appellate justices said her statements were part of an effort to stanch the flow of discretionary appeals from the Appellate Division to the state's high court. Her message to the First Department was relayed to at least three of the presiding justices of the appellate departments and discussed among the judges of those courts. According to judges who spoke with the Law Journal, some of whom asked to remain anonymous, her words affected many appellate justices' thinking on granting leaves of appeal.

“I would say it certainly enters into our analysis that she wants to choose her own docket. And nobody wants to annoy the chief,” said one judge.

DiFiore's push to discourage discretionary appeals from the lower courts has rankled some appellate justices who see it as limiting their discretion and interfering with their desire to vote based on their conscience, according to interviews with 10 current and former appellate justices. While it's not the first time a chief judge has sought to do this, it is a distinct change from how the court operated under former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman.

Former Justice David Saxe, who served during DiFiore's first year as chief judge, said he understood the chief judge's desire to control the high court's docket.

“But to the extent that the appellate division has the authority in certain instances to grant leave, the Court of Appeals shouldn't try to affect that discretion that the Appellate Division has,” Saxe told the Law Journal.

Court of Appeals spokesman Gary Spencer declined to confirm or deny DiFiore's stance, stating in an email that “this issue has been around for decades” and had “generally been addressed in conversations among colleagues of the Court of Appeals and the Appellate Division.”

Spencer added, “Judges of the Court of Appeals are in the best position to take a broad view of the issues that are percolating in all four departments of the Appellate Division as well as the cases currently pending on its docket and to know which cases raise the most important issues, the best time to bring those issues before the court and what ancillary issues in a given case might affect the court's review.”

DiFiore declined a request for an interview.

Initial indications clearly show the direction the court is headed in.

Little changed during the leadership transition in 2016. But in 2017—the first full year of DiFiore's tenure as chief judge—the 80 civil cases handled by the court was the lowest since at least 2001, according to statistics provided by the Court of Appeals and state court administration.

Statistics for 2017 showed appeals the high court accepts cut roughly in half. At the same time, the number of discretionary appeals sent to the court by appellate panels also dropped compared to recent years. Mandatory appeals, however, were up slightly.

These trends were the primary reasons for the decrease in civil dispositions. At the same time, the appellate courts' case resolution output and the overall number of civil cases that made their way to the Court of Appeals remained relatively consistent.

Litigants on the losing side of a final appellate decision in civil cases may, by statute, seek leave to appeal from the panel that decided the case or directly from the Court of Appeals. If the order is not final, the only option is to seek leave from the Appellate Division.

There is a right to appeal if two judges dissented from the decision. Otherwise in civil cases the losing litigants have to ask the panel for leave. The high court has no option but to hear the appeal once leave has been granted by the appellate department.

In criminal cases, litigants have a choice of going to any judge on the original panel or the Court of Appeals. If a judge dissented on the original decision, the parties often appeal to that judge.

The discretionary leaves, particularly on nonfinal orders, have drawn the ire of DiFiore, according to judges privy to the discussions. And DiFiore apparently has followed a path taken by former Chief Judge Judith Kaye, who similarly sought to limit appeals, according to former jurists.

Judges who were disquieted by DiFiore's entreaties told the Law Journal her efforts were overreaching into their legitimate authority.

They said discretionary leaves help provide clarity when a split occurs among the departments or when further interpretation of precedent is needed. They also believe their exposure to thousands of cases a year reveals issues of statewide importance that deserve the Court of Appeals' attention.

Presiding justices of the First and Second departments said their courts knew the chief judge's opinion, but would sometimes need to disregard it.

“If we think there's an issue that needs to be decided we will grant leave notwithstanding the Court of Appeals' view on this,” said First Department Presiding Justice Rolando Acosta.

“I think the judges are aware of what the chief judge's views are and the views of the Court of Appeals and every time an application comes up for leave of appeal I'm sure the judges take those views into account but each judge has to vote his or her conscience,” said Second Department Presiding Justice Alan Scheinkman.

Third Department Presiding Justice Elizabeth Garry told the Law Journal that her department generally takes a different tack in granting leaves. The Third Department is usually “restrained” in granting leaves of appeal, in deference to the Court of Appeals.

“It's our view that the highest court is better poised to analyze and make that choice,” she said.

Garry noted the Third Department drove cases to the high court only sparingly.

“I did not feel that was part of our traditional approach,” she said.

Fourth Department Presiding Justice Gerald Whalen said he had no recollection of a “directive” from the chief judge regarding appeals to the high court. Like Garry, Whalen said his court grants leave infrequently.

Yet Whalen made it clear that his court would give “serious consideration” to sending up cases that present a novel issue or has split the departments.

Albany Law School professor Vincent Bonventre said the Court of Appeals is a “policy-making court”—its job is to settle the substantive issues of law for the state. He said he understood the frustration when lesser cases clog the docket.

Legal observers' reactions ranged from general support to qualified concern.

Mark Zauderer, name attorney at Ganfer Shore Leeds Zauderer in Manhattan, said he understood the tension.

“In this area, there's no right or wrong,” said Zauderer, who argued two cases in front of the Court of Appeals this year. “Each participant in the appellate system has an understandable point of view, but at the end of the day it's natural for the reviewing court to try to make its own determinations as to what cases to hear.”

But Richard Emery, a founding partner at Emery Celli Brinckerhoff & Abady in Manhattan, said that making the Appellate Division reluctant to grant leave could cut off an avenue for settling unanswered questions in state law.

“If the appellate divisions honor that request, it may well have the consequence of circumscribing the guidance that the New York Court of Appeals has traditionally given the courts and lawyers concerning open questions of New York law,” he said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Prosecutors Ask Judge to Question Charlie Javice Lawyer Over Alleged Conflict

Trending Stories

- 1Florida Judge Tosses Antitrust Case Over Yacht Broker Commissions

- 2Critical Mass With Law.com’s Amanda Bronstad: LA Judge Orders Edison to Preserve Wildfire Evidence, Is Kline & Specter Fight With Thomas Bosworth Finally Over?

- 3What Businesses Need to Know About Anticipated FTC Leadership Changes

- 4Federal Court Considers Blurry Lines Between Artist's Consultant and Business Manager

- 5US Judge Cannon Blocks DOJ From Releasing Final Report in Trump Documents Probe

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250