Fine-Tuning Your Service of Process Clause

In their International Litigation column, Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky discuss a recent decision which invalidated service of process made in accordance with a provision allowing service of process by overnight courier and provide drafting tips to avoid such problems in the future.

November 28, 2018 at 02:45 PM

9 minute read

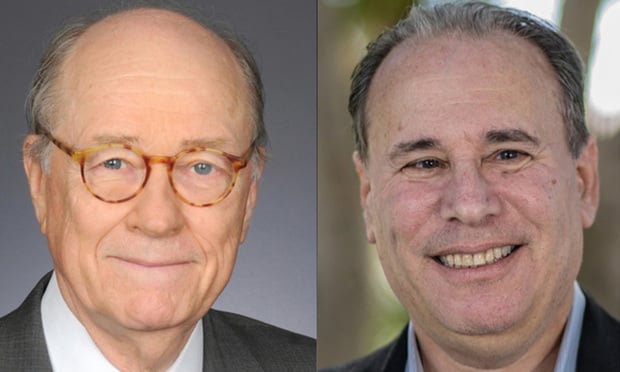

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

It happens innumerable times, almost by rote. Lawyers draft contracts and, in order for the parties to avoid the specific procedural requirements concerning service of process (especially outside the country), they include a provision that service of process may be accomplished by, for example, using mail or overnight courier. A recent state appellate court decision in California invalidated service made in accordance with such a clause. This article discusses that decision and suggests practices to avoid a similar result.

The case in question is Rockefeller Technology Investments (Asia) VII v. Changzhou SinoType Technology Co. (Cal. Ct. App. 2018), which arose out of a transaction between Changzhou SinoType Technology Company, Ltd. (SinoType), a Chinese company, and Rockefeller Technology Investments (Rockefeller), an American investment partnership. When the relationship soured, Rockefeller pursued contractual arbitration in Los Angeles, SinoType did not participate in the arbitration, and a default award was issued for about $414 million. The award was confirmed and judgment entered in state court in California, again in a proceeding in which SinoType did not participate. Approximately 15 months later, SinoType moved to set aside the judgment.

The contract included a provision that “[t]he parties shall provide notice in the English language to each other at the addresses set forth in the Agreement via Federal Express or similar courier, with copies via facsimile or email, and shall be deemed received three business days after deposit with the courier.” The “address” for SinoType was in China. The contract further provided for service of process to be made in accordance with the notice provision. When Rockefeller sued to confirm the judgment, it served SinoType by FedEx. SinoType argued that Rockefeller failed to serve the summons and petition to confirm the arbitration award in the manner required by the Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters (the Hague Convention). Nov. 15, 1965, 20 U.S.T. 361, T.I.A.S. No. 6638. The trial court rejected the improper service argument, holding:

[t]o allow parties to enter into a contract with one another and then proceed to unilaterally disregard provisions out of convenience, like the one at issue here, would allow parties to simply return to their respective countries in order to avoid any contractual obligations.

SinoType appealed.

In the United States, state law generally governs service of process in state court litigation. However, by virtue of the Supremacy Clause, the Hague Convention preempts inconsistent methods of service prescribed by state law in all cases to which the Convention applies. The centerpiece of the Hague Convention is the “Central Authority,” which receives requests for service from other contracting states. Service is ordinarily accomplished through the Central Authority, although some alternative methods for service are provided for as well.

More specifically, Article 10 of the Hague Convention provides for alternative methods of service if permitted by the “State of destination.” One such alternative is service through postal channels. China, however, is one of many countries that ratified the Hague Convention with a reservation that specifically states that the methods for service under Article 10 are not available. Accordingly, it was clear that, under the Hague Convention, service by FedEx (considered postal channels by the court) was not effective.

The question for the appellate court was whether the lower court was correct in holding that parties may agree on a method of service of process not authorized by the Hague Convention. The appellate court answered that in the negative. The Hague Convention applies to “all cases, in civil or commercial matters, where there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.” The Supreme Court has held that this language “is mandatory.” Volkswagenwerk Aktiengesellschaft v. Schlunk, 486 U.S. 694 (1988). Further, the Hague Convention emphasizes the right of each contracting state to determine how service shall be effected. The court explained that this meant that the state, rather than the citizens of such state, has the right to determine how service is to be made. Because, according to the court, parties may not contract around the requirements of the Hague Convention, the service of process that complied with the parties' agreement, but not with China's reservation under the Hague Convention, was invalid. Without valid service, the trial court did not have jurisdiction over SinoType and the resulting judgment was therefore void.

The authors are surprised to see how few cases there are on this issue. They have not been able to find any cases that have reached a similar result to that of the court in Rockefeller Technology. The Rockefeller Technology court said that there are only two reported decisions that, arguably, go the other way, but refused to follow them.

One of those cases, Alfred E. Mann Living Trust v. ETIRC Aviation S.A.R.L., 910 N.Y.S.2d 418 (1st Dep't 2010), concerned a note and guaranty, each of which included a provision under which the guarantor agreed to the exclusive jurisdiction of the New York courts and “waive[d] personal service of the summons, complaint and other process in any such action or suit.” The guaranty further provided that notices under the guaranty could be provided in accordance with the related funding agreement, which authorized notice or service to be made to either of two specific email addresses. The plaintiff used one of those addresses to serve its initial pleading and the guarantor moved to dismiss for improper service of process.

The court noted that parties are free to contractually waive service of process. As the court explained:

By definition, such waivers render inapplicable the statutes that normally direct and limit the acceptable means of serving process on a defendant. Indeed, a stipulation waiving service confers jurisdiction, precluding the defendant from successfully challenging the court's jurisdiction over him.

78 A.D.3d at 141. In response to the guarantor's argument that service on him by email while he was in the Netherlands ran afoul of the Hague Convention, the court said that there is nothing in the Convention that prevents waiver of service of process by contract. The Rockefeller Technology court said that it was refusing to follow this decision on the ground that it lacked any analysis of the Hague Convention.

In fact, though, the issues in the two cases were different and it would have made more sense for the appellate court in Rockefeller Technology to point out the important distinction. Indeed, the Rockefeller Technology court specifically noted that the Hague Convention applies “where there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.” In the case of a waiver of service of process, however, there is no occasion to transmit documents for service abroad. Rather, because of the waiver, there is no service at all. Alfred E. Mann is therefore not a decision on the issue of whether parties may contractually agree on methods of service other than those permitted under the Hague Convention.

The other relevant case, Masimo v. Mindray DS USA, 2013 WL 12131723 (C.D. Cal., March 18, 2013), dealt with a dispute regarding patent infringement and alleged breach of a purchasing and licensing agreement. The agreement provided for disputes to be heard in the California courts and permitted service of process to be made in accordance with the notice provision in the contract, which allowed for delivery “by hand or by postage prepaid, first class, registered or certified mail, return receipt requested.” The summons and complaint were served in China by return receipt mail. The defendant moved to dismiss the complaint, arguing that service was not made in accordance with the Hague Convention.

The court denied the motion. It referred to the general rule that parties may agree on a method of service of process that would not otherwise be permitted under Rule 4 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. As for the Hague Convention and the holding in Schlunk (noted above) that it is mandatory, the court said:

Schlunk did not involve parties contracting around the Hague Convention, and therefore, the Supreme Court did not need to decide the issue in that case. The Court sees no reason why parties may not waive by contract the service requirements of the Hague Convention, especially given that parties are generally free to agree to alternative methods of service.

Id. at *13. The Rockefeller Technology court refused to follow this case because it said its reasoning was too cursory.

The Rockefeller Technology decision is currently on appeal. Perhaps it will be reversed. But even if it is, courts in other states might rule the same way in the future. There is no need for parties to put themselves in a position of risk on this issue. There are two ways to make certain that the question of compliance with the Hague Convention does not become an issue. The first was mentioned above: if the contract includes a waiver of service clause, then there is no occasion to serve process and the Convention will not apply.

The second method also takes advantage of the fact that the Hague Convention applies only when service has to be made outside the United States. The difficulty in Rockefeller Technology was brought about by the fact that service by courier was made in China and, therefore, it was necessary to comply with China's reservation under the Hague Convention. The plaintiff would have been in a different position had the contract instead required the Chinese party to appoint an agent for service of process in the United States. In that scenario, when it came to serve the petition, “service,” notwithstanding that it would have been on a Chinese party, would have been in the United States and the Hague Convention would never have been triggered.

In short, lawyers have the opportunity to make certain that their domestic clients are never put in the position of worrying about whether they have complied with the requirements of the Hague Convention. When drafting service of process clauses, they should try to make clear that there is no requirement for “service” on a foreign counterparty to be made outside the United States.

Lawrence W. Newman is of counsel and David Zaslowsky is a partner in the New York office of Baker McKenzie. They can be reached at [email protected] and david.zaslowsky@bakermckenzie.com, respectively. Kirsten Jackson, a law clerk in the New York office, assisted with the preparation of this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Unraveling of Sean Combs: How Legislation from the #MeToo Movement Brought Diddy Down

When It Comes to Local Law 97 Compliance, You’ve Gotta Have (Good) Faith

8 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Adding 'Credibility' to the Pitch: The Cross-Selling Work After Mergers, Office Openings

- 2Low-Speed Electric Scooters and PIP, Not Perfect Together

- 3Key Updates for Annual Reports on Form 10-K for Public Companies

- 4When Words Matter: Mastering Interpretation in Complex Disputes

- 5People in the News—Jan. 28, 2025—Buchanan Ingersoll, Kleinbard

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250