New York Minimum Salary Thresholds Set to Increase for Exempt Employees

Effective Dec. 31, 2018, the minimum salary that employers must pay New York employees to be exempt from overtime under an executive or administrative exemption will increase.

December 20, 2018 at 02:35 PM

7 minute read

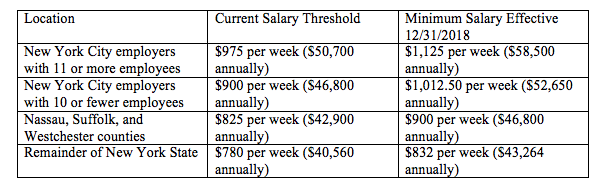

Effective Dec. 31, 2018, the minimum salary that employers must pay New York employees to be exempt from overtime under an executive or administrative exemption will increase:

Effective Dec. 31, 2018, the minimum salary that employers must pay New York employees to be exempt from overtime under an executive or administrative exemption will increase:

Below are some possible approaches to consider.

While pay raises may be an appropriate response to the new minimum thresholds, employers should carefully consider all of their options before taking action. In some cases, it would not be prudent to simply increase the salaries of all employees currently classified as overtime exempt without evaluating other alternatives to ameliorate the detrimental business impact that a sudden and dramatic increase in labor costs would likely cause.

First, if an employee is slightly below the relevant salary threshold, an increase in salary may be warranted.

Second, for other employees, the company could consider reclassifying exempt employees as salaried-nonexempt. Such employees would be entitled to overtime pay for hours worked over 40 in any given workweek, but the company could prohibit overtime entirely or set strict limits on the amount of overtime hours such employees are permitted to work. To the extent it is not currently doing so, the employer should take steps to ensure that all work time is accurately recorded so that overtime may properly be paid in this scenario.

Notably, under federal law (FLSA), nonexempt employees must receive overtime pay at the rate of 1½ times their regular rate of pay for all hours worked over 40 in a workweek. However, New York State Labor Law only requires an overtime rate of 1½ times the state minimum wage for any overtime hours, regardless of the amount of their regular rate of pay, if the employee is exempt from overtime under the FLSA but still entitled to overtime under New York law solely because of the increased salary threshold. As of Dec. 31, 2018, the New York state minimum wage is as follows:

• $15.00 per hour for businesses in New York City with 11 or more employees;

• $13.50 for businesses in New York City with 10 or fewer employees;

• $12.00 per hour in Nassau, Suffolk and Westchester counties; and

• $11.10 per hour in the remainder of New York state.

Assuming that an employee in New York City meets the FLSA exemption (which currently requires a minimum salary of $455 per week, or $23,660 per year), then for each hour worked over 40 in a given workweek overtime would only be paid at the rate of $22.50, not 1½ times the regular rate of pay. Under this system, employees would be paid overtime for hours worked over 40 in a week, and the company would have the discretion to either prohibit overtime work in its entirety or strictly limit the number of overtime hours that may be worked (with the understanding that employees must still be paid for overtime hours worked if they violate those restrictions). This would potentially result in a lower increase in labor costs than simply raising annual salaries across the board to $58,500, particularly if the company takes appropriate steps to limit overtime hours.

Third, the company could review the exemption status of employees more generally to determine proper classification and, for newly converted salaried, nonexempt employees, evaluate whether any such employees might satisfy the “fluctuating workweek” method of compensation. An employer is permitted to use the “fluctuating workweek” method when each of the following conditions is met:

• There is a clear mutual understanding between the employer and the employee that a stated fixed salary is straight-time compensation for all hours worked each workweek, whatever the number of such hours;

• The employee's hours fluctuate from week to week;

• The employee is actually paid a fixed amount as straight time pay for whatever hours the employee works in a workweek, such that if an employee does not work a full work week due to personal obligations, etc., he/she is still paid a full week's salary, with no deductions for hours not worked;

• The amount of the salary is sufficient to provide compensation to the employee at a rate not less than the applicable minimum wage for all hours worked in any workweek; and

• The employee is paid an additional amount for all overtime hours worked (i.e., hours over 40 in any given workweek) at a rate not less than 1/2 the employee's regular hourly rate of pay—such 1/2 rate would vary week-to-week depending upon the number of hours worked by the employee in such week.

Under the “fluctuating workweek” scenario, an employee paid an annual salary of $50,700 would be eligible for overtime for hours worked over 40 in a week at a rate of 50 percent of his regular rate of pay for each overtime hour worked (with the regular rate calculated by dividing the fixed weekly salary by the number of hours worked that week), provided the requirements set forth above are satisfied (which would likely not be the case for all employees). Although there would be an increased administrative burden given that an employee's regular rate of pay (but not fixed base salary) for purposes of calculating overtime may vary on a weekly basis, this approach could result in savings for large employers as compared to a blanket increase in pay for all New York-based employees currently classified as exempt.

Fourth, the company could consider a “Belo” plan, which provides for an exception from overtime pay requirements for certain employees with duties necessitating irregular hours of work. The exception applies if there is a written agreement to provide the employee with a weekly guaranteed salary for no more than 60 hours at a regular rate of pay that is not less than the applicable minimum wage and compensation at not less than one and one-half times the regular rate of pay for all hours worked over 40 in a workweek. This would allow otherwise nonexempt employees to receive the same amount of total compensation each week, regardless of the number of overtime hours worked (up to the maximum number of hours guaranteed in the agreement, which may not exceed 60). However, a Belo plan may be implemented only for employees whose duties require irregular hours of work which the employer cannot reasonably control or anticipate. Thus, the hours should not vary according to a predetermined schedule, or vary from week to week at the discretion of the employer or employee, but rather should change in a way that cannot be controlled or anticipated with any degree of certainty because of the nature of the employee's duties. Irregularities caused by absences for reasons unrelated to the nature of the duties being performed—such as personal reasons, illness, vacations, holidays, or scheduled days off—do not satisfy the requirements for irregular hours of work. Moreover, the hours worked must fluctuate above and below 40 hours per week.

Finally, the company could consider other options such as adding staff so that fewer employees are needed to work overtime hours when they are converted to nonexempt status or lowering base salary and allowing employees to make up the difference through overtime.

Complying with applicable wage and hour laws is critical to the functioning of any business.

Daniel Turinsky is a partner at DLA Piper.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Unraveling of Sean Combs: How Legislation from the #MeToo Movement Brought Diddy Down

When It Comes to Local Law 97 Compliance, You’ve Gotta Have (Good) Faith

8 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Public Notices/Calendars

- 2Wednesday Newspaper

- 3Decision of the Day: Qui Tam Relators Do Not Plausibly Claim Firm Avoided Tax Obligations Through Visa Applications, Circuit Finds

- 4Judicial Ethics Opinion 24-116

- 5Big Law Firms Sheppard Mullin, Morgan Lewis and Baker Botts Add Partners in Houston

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250