Jewish Heirs' Worldwide Fight to Reclaim Nazi-Stolen Art Plays Out in Manhattan Courts

A movement by Jewish heirs to reclaim valuable Nazi-looted art scattered worldwide has grown. And Manhattan's courts, both federal and state, are considered to be among the few places in the world where they can get a fair and sophisticated legal hearing on their claims.

December 26, 2018 at 12:01 AM

14 minute read

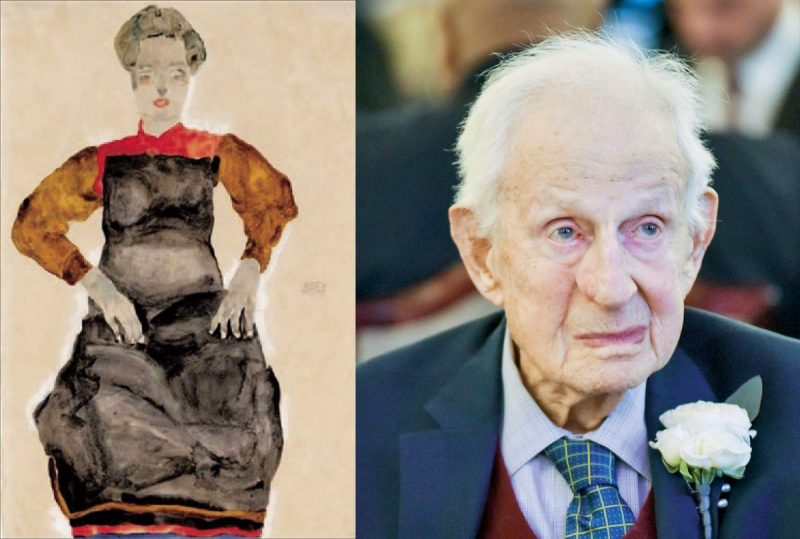

“Woman in Black Pinafore” by Egon Schiele, former Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau

“Woman in Black Pinafore” by Egon Schiele, former Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau

As worldwide efforts by Jewish heirs to reclaim Nazi-looted art continue to surge—a movement that some say former Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau fueled with his bold 1998 seizure of the MOMA's “Dead City III” painting—an art-restitution lawsuit launched in Manhattan state court appears to be growing in importance.

Impassioned oral argument unfolded in the case earlier this month before a lively Appellate Division, First Department bench, with justices challenging the lawyers while often barely waiting for each other to finish, or repeating a question until a better answer was given.

Meanwhile, a database in Europe that lists works believed to have been Nazi-seized during World War II has removed certain paintings, further stirring the debate in New York and well beyond.

And even within Manhattan's courts, there are divergent rulings in Nazi-looted art restitution cases.

The lawsuit, Reif v. Nagy, was launched in 2015 by Jewish heirs of a 1930s Austrian-Jewish entertainer, Fritz Grünbaum, who was a major art collector and public critic of Adolf Hitler. The heirs are trying to win the rights to two highly valued paintings, “Woman in Black Pinafore” (1911) and “Woman Hiding Her Face” (1912), once owned by Grünbaum and created by Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele.

At the trial level, they won summary judgment, and according to the heirs' attorney, Raymond Dowd, a Dunnington Bartholow & Miller partner specializing in intellectual property and art cases, the case is being followed by the Austrian legal community and by others in Europe and the U.S. who will look to it—once fully decided—for guidance.

In addition, the many cases springing up across continents over the provenances of allegedly Nazi-stolen art are known to be murky and difficult for judges and litigants alike. And Manhattan's courts, both federal and state, are considered a crucial staging ground for them because they are considered to be among the few places in the world where such claims can get a full, fair and sophisticated hearing, multiple lawyers representing Jewish heirs say.

And lawyers on both sides of such cases say those courts are viewed as central in the larger fight because they preside over one of the world's museum capitals, New York, where numerous pieces allegedly plundered by Nazis are shown.

Reif is taking on increased meaning, some art world members and lawyers contend, in the wake of a controversial move made by an important German database of likely Nazi-stolen art. The database, operated by the German Lost Art Foundation and often hailed for publishing more than 100,000 detailed provenance reports, has delisted 63 Egon Schiele works, thereby indicating that, based on information it has received, the pieces weren't stolen.

The works delisted include Schiele's celebrated “Dead City III,” as well as the works at issue in Reif, “Woman in Black Pinafore” and “Woman Hiding Her Face,” paintings valued together at $5 million.

The delisting, meanwhile, stands in opposition to Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Charles Ramos' opinion issued last April in Reif, in which he explained, while granting the heirs' ownership of the Schieles, why the paintings were looted by Nazis who may have been pointing a gun at Grünbaum as he signed over title from a concentration camp.

Dowd, one of those publicly criticizing the German foundation, is now claiming that its “unthinkable” removal decision is damaging his clients' separate legal effort in Austria over Schiele works there—a battle he said is meandering through an Austrian legal system with “no transparency, no due process, no right to appeal.”

“It has a strong negative affect,” he said in a recent interview. “[The foundation] is essentially using this database to help launder stolen art.”

“I think Germany is showing its defiance of the New York courts,” he said.

But the foundation—whose database reportedly presents detailed reports on 170,000 allegedly Nazi-stolen pieces, plus summaries of far more objects—disputes that it has done anything other than follow evidence.

In an email, foundation spokeswoman Freya Paschen said that “not even the court ruling of Judge Ramos in New York has produced any new historical facts about the provenance of these particular [63 Schiele] works.”

“The fact that Fritz Gruenbaum was persecuted by the Nazis is not contested,” Paschen said, but “this does not mean that the entirety of Gruenbaum's art collection must have been lost due to Nazi persecution.”

She also pointed out that “this rare case affected 63 works, whereas 163 other objects [from Schiele] are still on record” in the database as stolen.

'How Do We Know?'

At the Reif argument Dec. 13, the German foundation's decision did not come up, but the appeal questions over the two Schieles in dispute flew out with vigor.

It was hard to determine a leaning from the judicial panel as a whole, but the five justices sitting atop the ornate courtroom's bench had come prepared. The red “time's up” light was on for at least five minutes for Thaddeus Stauber, the attorney for defendant art dealer Richard Nagy, but the judges peppered him anyway.

Justice Peter Tom asked Stauber, “Assuming you identified and matched these paintings, then we go into the sister-in-law” of Grünbaum, who Nagy has argued obtained good title to the works despite Grünbaum's persecution. “How could she possibly have legal title?” Tom said.

Tom later came back to Stauber again: “Is there something in the record that shows the sister-in-law had legal title—not possession, legal title?”

Addressing Dowd, a justice asked, “How we do we know these two particular artworks were part of the collection of Schieles believed to be looted?”

“We're able to tie these 63 [allegedly looted] artworks together,” Dowd said while citing evidence.

At another point a judge asked Dowd, “Several experts … offer alternative explanations [of the two paintings' provenance]. How does Judge Ramos reject those as a matter of law? Why don't [they] raise an issue of fact?”

Stauber, a Nixon Peabody partner based in both New York and Los Angeles, pleaded throughout the session for a trial on the merits rather than affirmation of Ramos' ruling for the heirs.

“That's all we're asking for,” he told the justices, contending that Ramos had decided to “pick and choose” what he found true and not. And Stauber argued that each side had “diametrically opposed experts” on the paintings' provenance, and therefore a trial was needed.

Dozens of blocks away from the courtroom in his Lower Manhattan chambers, Ramos, speaking by phone, said shortly before the argument began that he'd be watching on live stream.

He declined to talk about the suit's merits or the reasoning he'd laid out in his opinion, but he did offer a broader thought: “It's a terrible period of history,” Ramos said, referring to the Holocaust. “I fear that a decision like mine is too little, too late, but we do what we can.”

Morgenthau and the 'Washington Principles'

The Reif case traces back to the Nazis' arrest of Grünbaum, his imprisonment at the Dachau concentration camp, where he later died, and what happened to his 449-piece art collection, 81 of them Schieles.

The plaintiffs in the case are Milos Vavra, an heir of Grünbaum's sister, along with Timothy Reif and David Fraenkel, who are co-executors of the estate of Leon Fischer, Dowd said. Fischer is descended from Grünbaum's wife's sister.

The paintings passed through the art world until, one day in 2015, the plaintiffs spotted them in Nagy's booth at an art show inside Manhattan's Park Avenue Armory. Dowd soon made a demand for their return.

Nagy and some other art dealers have argued that after the Nazi's stormed Grünbaum's home in 1938, his wife shipped off most of his art collection, possibly to family in Belgium.

It is without dispute that the Schieles disappeared until 1956, when Swiss art dealer Eberhard Kornfeld put 63 of them up for sale. But it was unclear in 1956 how, or from whom, he'd obtained them.

In 1998, as the Schieles' provenance became public debate, Kornfeld said he'd gotten them from Grünbaum's wife's sister, Mathilde Lukacs-Herzl.

The heirs, however, contend that documents Kornfeld has presented to back up his claim, including letters and receipts, are forgeries.

“Our handwriting expert concluded that these are likely forgeries,” Dowd said in an interview, but “Kornfeld never granted us access to the materials so that we could get a scientifically verified finding of forgery.”

For Justice Ramos, the Nazis' original persecution of Grünbaum, and how his art collection came into his wife's possession, was central to his decision.

He wrote that the Nazis arrested and took away Grünbaum, but left behind his wife, Elisabeth Grünbaum-Herzl. Then once Grünbaum was at Dachau, he was forced, perhaps at gunpoint, to sign power of attorney over his possessions to her.

“Although the Nazis confiscated Mr. Grunbaum's artworks by forcing him to sign a power of attorney to his wife, who was herself later murdered by the Nazis, the act was involuntary,” Ramos said. “A signature at gunpoint cannot lead to a valid conveyance.”

He also applied the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act (HEAR Act), a 2016 statute adopted by Congress that expanded the statute of limitations for Holocaust victims' heirs suing for artwork.

In addition, he pointed to the “Washington Principles”—a set of nonbinding tenets that various countries have agreed to use to promote the return of Nazi-stolen art. The principles grew out of an emotional 1998 conference in Washington, D.C., over Nazi-stolen art, which many say was sparked by Robert Morgenthau's ultimately unsuccessful attempt to subpoena and keep “Dead City III” from being shipped to Austria that year.

“We are instructed to be mindful of the difficulty of tracing artwork provenance due to the atrocities of the Holocaust era, and to facilitate the return … where there is reasonable proof that the rightful owner is before us,” Ramos wrote.

'Highly Unlikely'

Ramos' view on the Grünbaum-owned Schieles is disputed not only by art dealers. It has also been contradicted by a 2011 ruling from U.S. District Judge William Pauley III of the Southern District of New York.

In Pauley's Bakalar v. Vavra decision addressing a Schiele drawing called “Seated Woman With Bent Left Leg (Torso),” he wrote that his court had previously found that the drawing was possessed by Grünbaum prior to his 1938 arrest, and then by Lukacs-Herzl in 1956.

“The most reasonable inference to draw from these facts is that the Drawing remained in the Grünbaum family's possession and was never appropriated by the Nazis,” Pauley wrote. “The alternative inference—that the Drawing was looted by the Nazis and then returned to Grünbaum's sister-in-law—is highly unlikely.”

He also said, “What little evidence exists—that the Drawing belonged to Grünbaum and was sold by one of his heirs after World War II—suffices to establish by a preponderance of the evidence that the Drawing was not looted.”

Addressing the contention that Grünbaum's possibly coerced transfer was void, Pauley wrote: “Assuming arguendo that a transfer of property to a family member subsequent to a compelled power of attorney is void as a product of duress … there is no way of knowing whether the Drawing was in fact transferred pursuant to the power of attorney. It is equally possible that Lukacs obtained the Drawing before the power of attorney was executed.”

'A New York Story'

Following the Reif arguments, Dowd said he will await the First Department's decision with intense interest. He has called the suit “probably the most important art case of the late 20th century,” and one that “ended a controversy that has raged since … 1998” over whether Morgenthau was right to attempt to keep “Dead City III” from leaving the U.S.

Stauber said he believes Dowd is exaggerating the impact of Ramos' ruling. And in a recent email, Stauber—who has 20 years' experience in art-restitution cases—repeatedly addressed what he views as the proper role of United States courts in handling cases that are part of a worldwide movement and fight.

“The U.S. courts' role under the HEAR Act is to allow for merits-based trials to resolve claims that are in dispute,” he wrote, adding, “When a claim goes to court, it is only after we have shared the provenance research [with opposing parties] and have tried to reach a fair and just resolution.”

Addressing cases where international law or facts are at issue, he said, “U.S. courts must carefully consider whether taking on a case, especially if a claims panel in that country has been made available … is within the courts' limited jurisdictional mandate.”

He added, “The U.S. is not the only country with an independent judicial system, and the interpretation and application of foreign laws in U.S. proceedings risks placing a U.S. court on tenuous ground.”

Dowd disagreed with all of Stauber's points, including his view on the role of U.S. courts in international controversies over Nazi-looted art.

“The United States won World War II, as did the Allies,” he said. “Part of the victory was the restitution of property to Nazi persecutees,” he continued, and “any post-war law erected [by another country] in violation of that principle undermines the treaty obligations of all of those countries.”

“Our policy is to undo Nazi spoliation, but throughout Eastern Europe and Western Europe they have set up roadblocks to frustrate the claims of Holocaust victims,” Dowd said. He added that “the U.S. State Department has charged U.S. courts with righting these wrongs and has lifted all limits on their jurisdiction.”

“And Nazi-looted art is a New York story,” Dowd said, “We are the museum capital of the world [and] we have to show leadership.”

Dowd said Morgenthau's decision to go after “Dead City III” in the hours before it would to be shipped to Vienna was a “truly historic moment” that became a driving force behind the Jewish heirs' movement today.

“He was taking on the power structure. It literally changed the entire legal and diplomatic landscape,” Dowd said.

Morgenthau Reflects

Though for Morgenthau—now of counsel at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz and still working at age 99—what he recalled in an interview about going after the Schiele works in 1998 was simply that it needed to done.

He called the German Lost Art Foundation's recent delisting of the 63 Schieles a “mistake,” and said that in 1998 “there was strong evidence [Dead City III] was stolen.”

“What we did, we would have done with any stolen property,” he said.

Morgenthau added that he could not have anticipated that the seizure would help lead to the Washington Principles and the fueling of expansive artwork litigation today.

But asked if he was proud that his action may have sparked efforts aimed at righting one of Hitler's wrongs, he answered without hesitation.

“Absolutely,” he said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Prosecutors Ask Judge to Question Charlie Javice Lawyer Over Alleged Conflict

Trending Stories

- 1Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 2Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

- 3'We Neither Like Nor Dislike the Fifth Circuit'

- 4Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

- 5Senior Associates' Billing Rates See The Biggest Jump

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250