Chief Judge's Inquiry Into Dissents Intrudes on Judicial Independence

When David Saxe, then age 74, wanted to continue as an associate justice at the Appellate Division, First Department, he was asked for his batting average. "I saw this request as an intrusion into the judicial independence of the court I sat on."

January 23, 2019 at 03:15 PM

7 minute read

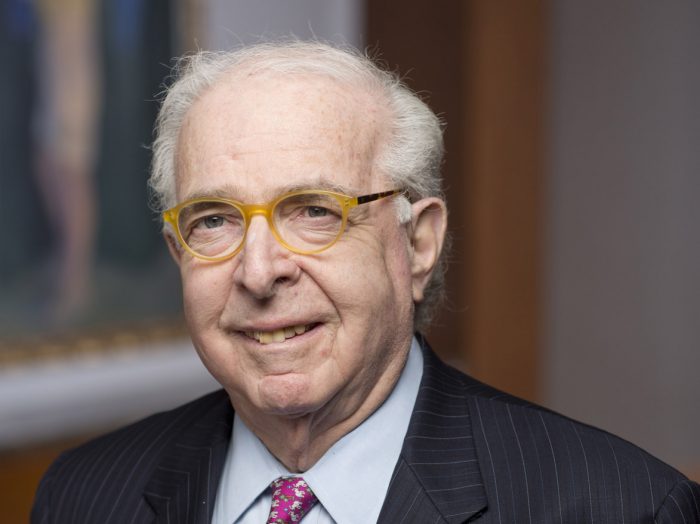

David B. Saxe

David B. Saxe

The New York Law Journal ran a front-page story headlined “DiFiore Presses Appellate Judges to Send Fewer Appeals to High Court” on Nov. 26. The focus of the piece was the chief judge's plan to have Appellate Division justices refrain from foisting certain appeals on the Court of Appeals – particularly, those arising from a grant of leave to appeal from non-final orders – a right however that belongs by statute to the Appellate Division. What the article pointed out was that there was likely to be ongoing skirmishes between the chief judge and the appellate divisions (most likely the Appellate Division, First Department) in this area.

The article did not deal with a related area of apparent concern to the court administration – what is perceived as an unnecessarily large number of dissents arising out of the Appellate Division, First Department, in particular.

I became aware of this concern or interest during the period of time leading up to my third (and final) certification. As most court observers are aware, certification is a process by which New York State Supreme Court justices, on reaching the mandatory retirement age of 70 may be entitled to serve for three two-year periods until reaching 76. Then, they are gone for good. The certification process is run under the watchful eye of the chief administrative judge who gets his marching orders from the administrative board headed by the chief judge. Under prior court administrations, certification was fairly automatic – especially if the justice had a reasonable work history and did not demonstrate any unusual fogginess in the area of mental acuity. It made management sense as well: the court system was getting an additional body to perform judicial tasks since upon certification the seat of the certificated judge opened up for purposes of electing a successor-judge.

Under the present court administration, justices seeking certification face a higher hurdle, as demonstrated by the fact that a number of them have already been denied certification.

But, for Supreme Court justices sitting on the Appellate Division and who were seeking certification – and through that designation being able to continue their appellate service, a new and unusual impediment arose.

I experienced the effect of this impediment during the run-up to my last certification (in 2016) when the then Acting Presiding Justice Peter Tom asked me to prepare a list of all the items making up my appellate “batting average.” I had never been asked for that statistic before and when I asked him what that “batting average” consisted of, he informed me that it would be comprised of a listing of my dissents measured against how they had fared at the Court of Appeals. The other member of the court who was seeking certification at that time was also asked for this statistic. The thrust of this request was clear: was I, for example, wasting time and even burdening the high court if these dissents increased the docket of the Court of Appeals, without any change in the decision previously made by the panel majority at the Appellate Division, First Department. I saw this request as an intrusion into the judicial independence of the court I sat on.

When I inquired of Acting Presiding Justice Tom about the origin and purpose of this new requirement, I was advised by him that it came from the top: “There's a new sheriff in town,” he remarked to me in answer to my inquiry. He confirmed that the purpose of this statistical edict was to impede what was perceived as unnecessary dissents which, when they became the subject of successful motions for leave, added unnecessarily to the work of the Court of Appeals.

Although I had written my fair share of dissents, I was not concerned with my own request for certification. I had at that time, plans almost in place for leaving the court system and returning to the active practice of law. Nevertheless, I was alarmed at what this new policy spelled out for the future of judicial independence, especially at the Appellate Division, First Department, a premier intermediate appellate court long recognized for its excellence and independent judicial analysis. Indeed the line-up of the First Department at that time of my departure and soon afterward, with the addition of four new associate justices, made the court as top-notch as it ever had been, comprised of a diverse, experienced and intellectually independent group of judges, led by a vibrant new presiding justice.

This topic became the talk of the lunchroom at the First Department for days. There was widespread concern among my then colleagues. Judges who were themselves immersed in the certification process or approaching it knew that they were in the cross-hairs of this new protocol; even younger judges not yet enveloped by the policy became enveloped by the warning it gave off.

I am afraid that the requirement of this seemingly harmless statistic portends a change of life for my old court and not one that ought to be in place.

While, as I have already pointed out, this intrusion on dissents is unwarranted, there are actually many positive reasons for encouraging or at the very least, tolerating the dissent, especially at an intermediate appellate court, before the law is actually settled.

I have found that a well put-together dissent often serves to improve the majority's ultimate writing in two ways, one, general and specific. Generally, it stimulates the intellectual exchange of ideas between two camps and specifically, it requires the majority to wrestle with the hard objections that can be directed in opposition. (1) It also encourages the majority writer to tighten and reinforce its analysis, by omitting unnecessary and unpersuasive arguments and turgid language, perhaps by acknowledging some limitations in the scope of its holding as well. (2)

Of course, not every dissent ought to be encouraged. A random dissent, short on analysis is probably more of an irritant than a real contribution to the judicial process. Dissents should be saved for important matters.

But the thoughtful dissent should not become part of what I see as a vindication statistic – that is, a mark against its author unless it results in the higher court reversing the Appellate Division on the basis of that dissent – a dissent the high court is otherwise not mandated by finality and two dissenting votes to take. The dissents that I am talking about speak to a common law legal tradition that prizes the independence of the individual judge to speak up.

Although the dissent may “serve no immediate purpose in the case at hand, … [it] may salvage for tomorrow the principle that was sacrificed or forgotten today.” (3) That important thought should continue to echo loudly.

Endnotes

- See, generally, Flanders, “The Utility of Separate Judicial Opinions in Appellate Courts of Last Resort: Why Dissents are Valuable,” 4 Roger Williams U. L Rev 401, 403 (Spring, 1999);

- See, Shepard, “Perspectives: Notable Dissents in State Constitutional Cases: What Can Dissents Teach Us?” 68 Alb. L Rev 337 (2005)

- Id. At 411, fn 31.

David Saxe served as an associate justice of the Appellate Division, First Department, for the last 19 years. In 2017, he joined Morrison Cohen as a partner. The views expressed here are his own.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Neighboring States Have Either Passed or Proposed Climate Superfund Laws—Is Pennsylvania Next?

7 minute read

Relaxing Penalties on Discovery Noncompliance Allows Criminal Cases to Get Decided on Merit

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 2Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

- 3'We Neither Like Nor Dislike the Fifth Circuit'

- 4Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

- 5Senior Associates' Billing Rates See The Biggest Jump

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250