Fraud as a Defense Against the Enforcement of International Arbitral Awards

In their International Litigation column, Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky write: Although fraudulently obtained arbitral awards are no doubt unenforceable in virtually every country, proving the taint of fraud presents legal and evidentiary challenges. A recent series of cases involving an award against the Republic of Kazakhstan shows the difficulties that can confront award debtors seeking denial of enforcement of awards against them on grounds of violation of public policy based on fraud.

January 23, 2019 at 02:45 PM

9 minute read

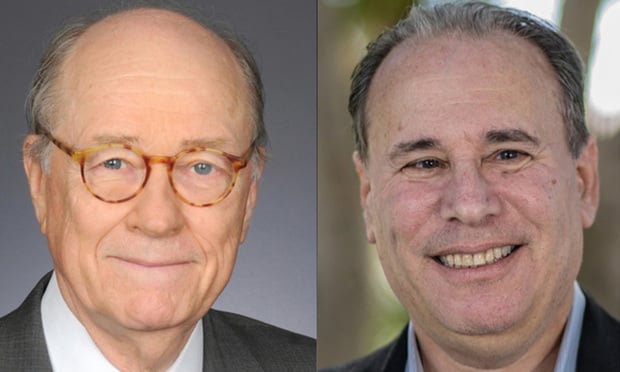

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

As the number of international arbitration cases has grown together with the size of the amounts awarded, anecdotal evidence shows that many losing parties to international arbitrations fail readily to pay the amounts awarded and, instead, seek refuge in the courts. One of the grounds on which some losing parties have sought to have courts deny confirmation or enforcement of awards is alleged corruption in the process by which the awards were made, in particular, fraud on the arbitral tribunal. The Federal Arbitration Act, in §10(a)(1), specifically refers to “corruption, fraud or undue means” as a basis for vacating arbitral awards. The United Nations Convention for the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (New York Convention) deals with fraud less directly: Article V(2)(b) of the New York Convention provides that awards that are unenforceable as contrary to U.S. public policy. U.S. courts have ruled that awards found to have been obtained through fraud to be unenforceable on public policy grounds. See, e.g., Enron Nig. Power Holding, Ltd. v. Fed. Republic of Nigeria, 844 F.3d 281 at 14 (D.C. Cir. 2016).

Although fraudulently obtained arbitral awards are no doubt unenforceable in virtually every country, proving the taint of fraud presents legal and evidentiary challenges. A recent series of cases involving an award against the Republic of Kazakhstan shows the difficulties that can confront award debtors seeking denial of enforcement of awards against them on grounds of violation of public policy based on fraud. In 2013, an arbitral tribunal sitting in Stockholm issued an award in favor of investors (the Stati) from Moldova against Kazakhstan. The tribunal determined that Kazakhstan had expropriated the oil and gas rights of the Stati in violation of its obligations under the Energy Charter Treaty and ordered it to pay damages of almost $500 million. One of the expropriated assets was a liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) plant, which the tribunal valued at $199 million, based on a bid previously presented to the Stati by a state-owned company, KMG.

In 2014, the Stati brought an action in the district court for the District of Columbia to enforce the award in the United States. Initially, Kazakhstan opposed confirmation of the award on five grounds under the New York Convention, none of which was an allegation of fraud. In June 2015, through discovery applications in the Southern District of New York, Kazakhstan obtained evidence that it said showed that the Stati had provided to KMG financial statements that falsely inflated the construction costs of the LPG plant, thereby allegedly inducing KMG to bid $199 million for it.

Based on that evidence, in April 2016, Kazakhstan filed a motion in the D.C. district court seeking leave to submit additional defenses in the form of its fraud allegations. However, for reasons that are not clear, Kazakhstan did not invoke the fraud theory regarding the inflated construction costs of the LPG plant. Rather, the motion contended that the Stati had obtained the award through fraud by submitting misleading evidence in the form of sworn testimony and expert reports concerning the valuation of the plant.

Since the arbitrators stated in their award that they had not relied on either parties' expert reports for the valuation of the LPG plant, the district court denied Kazakhstan's motion on the basis that the alleged fraudulent evidence had not been material to the award. The court stated: “it would not be in the interest of justice to conduct a mini-trial on the issue of fraud here when the arbitrators expressly disavowed any reliance on the allegedly fraudulent material.” Order of May 11, 2016 (Docket # 36, at 4) quoted in Stati v. Republic of Kaz., 302 F. Supp. 3d 187 at 8 (D.D.C. 2018).

It was only in its later motion for reconsideration that Kazakhstan raised its fraud defense based on the KMG bid. Since Kazakhstan had brought a motion to vacate the award in Sweden, the court stayed hearing the reconsideration motion until the completion of the Swedish proceedings. Unlike in its motion for leave filed before the D.C. court, Kazakhstan this time did present its fraud argument regarding KMG bid in the Swedish proceedings. Nonetheless, in December 2016, the Svea Court of Appeal of Sweden rejected Kazakhstan's fraud allegations, concluding that, “because the KMG bid was made prior to the initiation of the arbitration, the bid did not constitute per se false evidence, even if possibly incorrect information regarding the amount invested in the LPG plant was among the factors that KMG took into account when calculating the size of its offer.” (quoted in 302 F. Supp. 3d 187 at 13). The Svea Court of Appeal decision was upheld a year later by the Swedish Supreme Court.

After the award became final and binding, the D.C. district court lifted the stay and on March 23, 2018 denied Kazakhstan's motion for reconsideration. The court held that it had not erred earlier when it denied Kazakhstan's motion for leave to present additional defenses. The court said that the motion related exclusively to the allegedly false expert reports and testimony presented by the Stati in the arbitration proceeding on which evidence the arbitrators had not relied. Regarding Kazakhstan's attempt to introduce new facts in support of its fraud allegations, the court held that “since respondent is not claiming that the evidence of KMG's fraudulent inducement was not available to it at the time it filed its initial motion … the Court finds that those facts are improperly raised now.” 302 F. Supp. 3d 187 at 20.

Kazakhstan argued that the court had ignored federal court rulings that “it is not necessary to establish that the result of the arbitration would have been different if the fraud had not occurred.” See Karaha Bodas Co. v. Perushaan Pertambangan Minyak Dan Gas Bumi Negara, 364 F.3d 274, 306-07 (5th Cir. 2004) and Bonar v. Dean Witter Reynolds, 835 F.2d 1378, 1383 (11th Cir. 1988). Although the court recognized that an award obtained through fraud would be contrary to U.S. public policy, it rejected Kazakhstan's argument that it had placed undue emphasis in its earlier ruling on whether the alleged fraud affected the outcome of the award.

The court held instead that it had relied on the well established principle that a party seeking to resist enforcement of an award based on fraud must demonstrate only a connection between the alleged fraud and the decision. The court acknowledged that the D.C. Circuit had not clearly articulated the materiality standard necessary for vacating or denying enforcement of an award based on fraud. But the court applied the three-prong test applied by other courts to determine whether an award should be vacated as fraudulently obtained under §10 of the FAA. That test requires a showing that the fraud materially related to an issue in the arbitration. See Odeon Capital Grp. v. Ackerman, 864 F.3d at 196 (2d Cir. 2017).

Thus, the court held that a party seeking to invalidate an award on public policy grounds based on fraud must be able to point to at least some connection between the alleged fraud and the award, something it found that Kazakhstan had failed to do, since the allegedly false expert reports and testimony had not been considered by the tribunal. The court noted that the public policy defense to enforcement of the awards is to be construed narrowly, and the party invoking it bears a heavy burden of proving that the arbitral award was clearly contrary to the public interest. 302 F. Supp. 3d 187 at 22. See also TermoRio S.A. E.S.P. v. Electranta S.P., 487 F.3d 928 (D.C. Cir. 2007) (holding that a judgment is unenforceable as against public policy to the extent that it is “repugnant to fundamental notions of what is decent and just in the State where enforcement is sought.”); Karaha Bodas, 364 F.3d at 305-06 (stating that “the public policy defense is … to be applied only where enforcement would violate the forum state's most basic notions of morality and justice.”).

The issue of materiality of the fraud was an important part of the analysis done by the Svea Court of Appeal of Sweden. The Svea Court of Appeal of Sweden stated that “there can be no question of declaring an arbitral award invalid solely on the ground that false evidence or untrue testimony has occurred, when it is not clear that such have been directly decisive for the outcome.” (quoted in 302 F. Supp. 3d 187 at 12). The Swedish court further stated that “even if [the evidence] were proven to be false, it would not have changed the outcome of the arbitration…” (quoted in 302 F. Supp. 3d 187 at 13).

Not all courts have turned Kazakhstan away. On June 6, 2017, Kazakhstan obtained a ruling from a London court that, relying on the evidence of the fraudulent financial statements provided to KMG, concluded that it had established a prima facie case that the award was obtained through fraud. See Stati and the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2017 EWCH 1348 (Comm). In response, the Stati dropped efforts to enforce the award in London. To date, London is the only jurisdiction where Kazakhstan's fraud defense against the award has been accepted (enforcement actions in Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, where Kazakhstan has also brought its fraud allegations, are pending).

Lessons have been learned and no doubt will continue to be learned from this case in its various geographic manifestations regarding the burdens imposed on parties that suspect the existence of fraudulent or falsified evidence in an arbitration proceeding. Delays in obtaining evidence of the alleged fraud or raising the fraud allegation as soon as the evidence is found can make the difference between acceptance or not of the fraud defense. In the United States, asserting a fraud defense at the confirmation or enforcement stage, rather than at the arbitration proceedings, subjects the award debtor to a higher standard because “the public policy ground is exceedingly narrow, and courts are reluctant to find that its requirements have been meet.” Restatement of the Law Third, International Commercial Arbitration, §4-18, p. 252.

Lawrence W. Newman is senior counsel and David Zaslowsky is a partner in the New York office of Baker McKenzie. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively. Natalia Mori of the firm's Lima assisted in the preparation of this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Judgment of Partition and Sale Vacated for Failure To Comply With Heirs Act: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Morgan Lewis Says Global Clients Are Noticing ‘Expanded Capacity’ After Kramer Merger in Paris

- 2'Reverse Robin Hood': Capital One Swarmed With Class Actions Alleging Theft of Influencer Commissions in January

- 3Hawaii wildfire victims spared from testifying after last-minute deal over $4B settlement

- 4How We Won It: Latham Secures Back-to-Back ITC Patent Wins for California Companies

- 5Meta agrees to pay $25 million to settle lawsuit from Trump after Jan. 6 suspension

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250