Ira Gammerman, a Commercial Division Founder, Dies at 91

Justice Gammerman was known as an intelligent, tough, wise and wisecracking judge on the Commercial Division who handled many thousands of cases over a decadeslong career.

January 28, 2019 at 06:31 PM

5 minute read

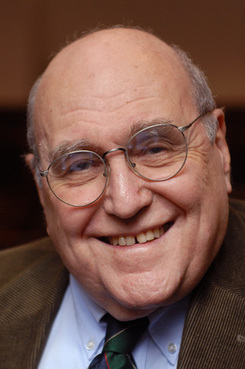

Ira Gammerman (Photo: Rick Kopstein)

Ira Gammerman (Photo: Rick Kopstein)Ira Gammerman, one of the founding justices of the Manhattan Supreme Court's highly regarded Commercial Division—who continued to carry a significant caseload for a decade after retirement in an arrangement with the state's commercial bar—has died.

He was 91. He passed away at his Manhattan home on Saturday.

An announcement from the funeral home handling the arrangements—circulated to the legal community Monday afternoon by longtime Manhattan Supreme Court Chief Clerk John Werner—did not list a cause of death.

Gammerman was known as an intelligent, tough, wise and wisecracking judge on the Commercial Division who handled many thousands of complicated cases over a decadeslong career. While viewed as fair and knowledgeable in the law—with strong views on a number of legal issues—his outsize personality also left a deep impression, sometimes becoming the most memorable part of a courtroom experience with him.

Purely in number of years and matters handled, he was a stalwart on the Commercial Division, which has risen to be considered among the most highly respected commercial courts in the world, often mentioned alongside London's commercial court as handling many of the world's most important, complex and high-value matters.

In 1993, Gammerman was assigned with three other Manhattan Supreme Court judges to kick off the Commercial Division pilot program, according to the Hawthorne Funeral Home announcement and a separate interview on Monday with Chief Clerk Werner. The division has since grown and prospered, and has leaped from initially being a part of just two counties' court systems to being found in 10 New York counties and districts.

But when Gammerman reached the mandatory retirement age of 76 in 2004, he was not done with the division and its weighty cases.

He was able to make an arrangement with the commercial-lawyer bar, according to Werner, to keep trying and deciding many of his 250 to 300 existing cases. He therefore carried a significant caseload for years, Werner said, and a larger load than what many retired justices, who become Judicial Hearing Officers, typically carry.

In all, the judge presided over many thousands of commercial cases, as well as many other types of cases in a 30-year judicial career. Moreover, he was a trial assignment judge on the Manhattan Supreme Court for about 10 years, Werner said.

Gammerman left an impression on lawyers, the state and litigants that will last for decades or longer.

Mark Zauderer, a commercial litigator and today a partner at Ganfer Shore Leeds & Zauderer, who appeared before Gammerman for many years, said on Monday that Gammerman was “extremely bright and quick—and he grasped issues immediately and followed them very closely and accurately when on trial.”

“He was a man of very strong convictions on legal issues, and very strong views on issues in cases he heard, but he was unfailingly courteous to trial counsel,” Zauderer said.

“And while he might at times express humor or sarcasm, it was never personally demeaning,” he said.

Zauderer also said that, “what particularly characterized him, was given the strong views, if he didn't agree with you on a legal issue, you would have move mountains to change his mind. But, he was unfailingly fair.”

Speaking of the judge's sharpness, Zauderer recalled a high-value employment dispute with an employee who sued a major corporation. During trial, Gammerman surprised Zauderer with his recall.

“I can remember cross-examining a witness, and he didn't appear to be listening carefully,” Zauderer recounted, “and 15 minutes later, when the witness gave testimony, he remembered precisely what the witness had said earlier and corrected him.”

Outside of court, in “bar circles,” Gammerman “was a gentleman, and he had a wonderful sense of humor and seemed to genuinely enjoy mixing with lawyers,” according to Zauderer.

A 2004 profile of Gammerman in the New York Times focused on his wit and shrewdness in courtrooms, including when litigants such as Woody Allen appeared before him. Near the start of the profile, Gammerman was called “a one-stop vending machine of justice.”

“He empanels multiple juries, issues frequent decisions, wisecracks and, when he is in the mood, takes over from the lawyers before him and questions the witnesses himself, all while typing away on other matters on a computer,” the profile said.

It continued, “Indeed, when Justice Gammerman warms to a well-argued case, life inside his courtroom can be sweet and entertaining. But dally a bit too much, or bend the facts in pursuit of a truth he cannot see, and judgment for the lawyers can be swift and, well, harsh. Witnesses are not spared, either.”

According to the funeral home announcement and Werner, Gammerman is survived by his wife, Margaret Taylor, a former New York City Civil Court judge, his children, Dan (Carolyn) Gammerman of Centerport and Judith (Hunter) McQuistion of Hastings on Hudson, and four grandchildren.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: Qui Tam Relators Do Not Plausibly Claim Firm Avoided Tax Obligations Through Visa Applications, Circuit Finds

'Serious Legal Errors'?: Rival League May Appeal Following Dismissal of Soccer Antitrust Case

6 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Sanctions Attorney for 'Frivolously' Claiming All Nine Personal Injury Categories in Motor Vehicle Case

Trending Stories

- 1States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 2Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 3Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 4Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

- 5Securities Report Says That 2024 Settlements Passed a Total of $5.2B

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250