'Bleed Out'—The Movie

In their Medical Malpractice column, Thomas Moore and Matthew Gaier discuss the HBO movie 'Bleed Out' by Steven Burrows about what happened to his mother, Judie, after a broken hip led to brain injury, and the lawsuit that followed.

February 04, 2019 at 02:45 PM

14 minute read

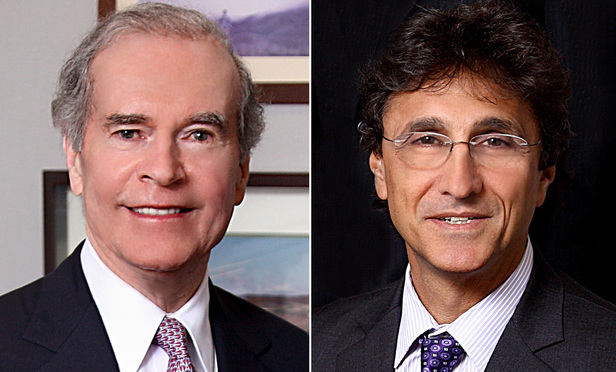

Thomas A. Moore and Matthew Gaier

Thomas A. Moore and Matthew Gaier

At the end of December 2018, HBO released a feature length documentary about a medical malpractice action. It was written, produced and directed by Steve Burrows, a comedy director, and it tells the story of what happened to his mother, Judie, as well as the lawsuit that followed. In addition to covering issues of medicine, law, and politics, the film poignantly portrays the extraordinary damage that flows from a brain injury that some may regard as less than catastrophic because the victim is able to walk and speak clearly. This film should be of particular interest to anyone who has had involvement with lawsuits stemming from medical negligence, including doctors, nurses, lawyers, judges, and perhaps even jurors who have sat on such a case in the past.

The Plot

The story started in June of 2009, when Judie, an active and independent 69 year-old retired special education teacher from Milwaukee, Wisc., fell and broke her hip. She was rushed to Aurora West Allis Medical Center in Milwaukee, and was operated on by her surgeon and family friend, Dr. Bauer. He had previously done two successful total knee replacement surgeries on her. After performing surgery on her hip, Judie underwent rehabilitation and was sent home. Her recovery from this surgery was difficult, and five months later she fell again.

Judie returned to the same hospital, where they determined that she had not broken her hip. They were prepared to discharge her, but she was in a great deal of pain, and at the family's insistence, she was admitted. During the hospitalization they determined that she had, in fact, broken her hip, and on the eighth day of the hospitalization Dr. Bauer decided to operate—the family would later learn that by mid-summer he had concluded that the June surgery was failing.

Judie had been on Plavix, a blood thinner, which must generally be discontinued several days prior to surgery. However, Dr. Bauer wanted to operate and Judie was cleared for surgery by her primary care physician, Dr. Lillie. A nurse actually made Dr. Bauer write into the chart that he was aware of the Plavix. They showed his handwritten entry with the unusual notation, “I am aware of Plavix—may affect bleeding.” The surgery lasted six hours, during which it is reported that she lost approximately half of her body's blood volume. Despite this extensive intra-operative blood loss, the anesthesiology record was described as “impeccable,” indicating no drop in blood pressure.

After the surgery, Judie was put in the ICU. This ICU, it is explained, was an electronic ICU or eICU, in which images captured on a camera in the patient's room were monitored by a physician at a remote location not in the hospital but somewhere at or near the airport. There was an ICU nurse present on the floor, but apparently, at least on this night, there was no ICU physician on the floor. Within an hour of being in the ICU, Judie's blood pressure plummeted, eventually going down to 50/30. Her family later learned that the ICU camera may not even have been on. On day one post-op, Judie was totally unresponsive. That continued on the second day, and when a neurologist evaluated her, it was determined that she was in a coma. She remained comatose for almost two weeks, and when she came out, she had sustained severe permanent brain damage. She had spastic paraplegia, had to relearn how to talk, eat and walk, and had severe cognitive disabilities.

Lawyering Up

Judie's brother, a retired physician, and her sister-in-law, a nurse, reviewed the chart shortly after she was found to be in a coma and advised her son, Steve, to hire an attorney. They felt that the anesthesia notes were “too perfect” and were likely falsified. Steve retained counsel, who explained to him that they would need an expert opinion that there was negligence before bringing suit, that 90 percent of malpractice cases that get tried in Wisconsin result in defense verdicts, that even if they prevail, there is a $750,000 cap on pain and suffering awards. It bears mention that several months before the film was released, the Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld that limitation in the case of a woman who lost all four limbs due to malpractice, reducing $15 million in noneconomic damages awards to the amount of the cap. See Mayo v. Wisconsin Injured Patients and Families Compensation Fund, 383 Wis.2d 1 (2018).

Although the lawyer obtained an expert opinion that the care Judie received had been substandard and that low blood pressure in the ICU with no doctor present caused her injuries, he withdrew from the case before filing suit because he determined that representing plaintiffs in medical malpractice actions was no longer worth his time and effort. They had to find another lawyer to take the case.

Continuing with Judie's saga, the bills were mounting, with her long-term care costing $6,000 a month. Her condition improved, but she continued to require assistance. She was able to speak well and could walk with the aid of a walker, but she had significant cognitive impairment, confusion and lack of judgement. She was determined to be incompetent after a neuropsychological evaluation. She wanted to go home, but could not live on her own and care at home would be even more costly than the facility. None of her family lived in Wisconsin, and her son, Steve, had to travel from Los Angeles to Wisconsin twice a month to take care of her affairs, disrupting his personal life and severely impeding his career.

The film does an excellent job portraying the emotional torture of persons with brain damage who outwardly appear healthy and who misperceive themselves as normal and capable, but in fact cannot function without assistance. One scene was uniquely demonstrative. Judie, who had been fiercely independent her whole life, desperately wanted to drive again and insisted she could do it. In an effort to prove to her that this was impossible, Steve took her to an empty parking lot to try. When she got behind the wheel, she did not know how to start the car. Once she started driving, her inability to drive safely on roadways with other vehicles was obvious to any observer. Yet, she maintained that she could do it.

The film also illustrates the enormous degree of hope that malpractice victims and their families place on the legal system. The malpractice action was critical to Judie's desire to return home and to Steve's ability to restore some semblance of normalcy to his life.

Investigative Work

Before the action was commenced, Steve undertook his own investigation. He recorded a meeting with the surgeon, Dr. Bauer, with spy-cams, significant footage of which appears in the film. Dr. Bauer disputed the suggestion that Judie did not get enough blood during the surgery, stating she was given 5 to 7 units and that the records indicate her blood pressure was fine. He stated that she was fine after the surgery, and that he did not understand why she was not waking up when he saw her the next morning.

He noted her blood pressure drop in the ICU, which he called “horrible,” and stated that she was not getting any care—this was “just not intensive care.” He wanted to know why Dr. Darmstadter, the ICU doctor, told him and Steve that she was doing fine. Dr. Bauer indicated that the use of a camera to monitor the patient in the ICU was borne by Aurora and it is “their vision of intensive care.” Most notably, he stated, “this isn't just a mistake” and “this is just plain goddamn sloppy medicine.” He said he would like an accounting as to why no doctor was there, and that he did not think the hospital would ever tell the truth. Notably, when questioned by a reporter after the film was released, Dr. Bauer stood by the “sloppy medicine” statement. See Cary Spivak, Surgeon stands by 'sloppy medicine' comments in HBO documentary about Aurora hospital, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Dec. 18, 2018.

Steve also recorded a meeting with a risk manager for Aurora, which owned the hospital. Aurora is a huge health care system, with 15 hospitals, more than 150 clinics, and 1,800 employed physicians and tens of thousands of employees. Steve asked the risk manager about an inquiry he had made 17 months earlier concerning financial assistance from the hospital. At the time, she had she said she would get back to him but she never did. She now said that the hospital would not provide such assistance, and that this would only happen if they feel they did something wrong and they do not feel that. She then asked if he had ever talked to Dr. Bauer, while also noting that Judie had pre-existing co-morbidities. Her advice was to tell his mother to celebrate the good times and move on.

Depositions

Once the litigation was started and discovery ensued, there were a total of 30 depositions, which would include fact witnesses and experts. While no one denied that the brain damage happened, everyone denied responsibility. Several segments of videotaped depositions were shown in the film. One set of those excerpts revealed the following: Dr. Bauer testified that he had no idea at the time of the surgery how low her hemoglobin and hematocrit had been, and indicated that the anesthesiologist was taking care of that.

The anesthesiologist, Dr. Hoyme, indicated that Dr. Bauer said to him that he had operated on patients on Plavix in the past, that he was aware of it and that he felt it was safe to proceed. Dr. Bauer indicated that he would only go forward with the surgery if the primary care physician cleared her. The primary care physician, Dr. Lillie, testified it was not his role to tell Dr. Bauer whether or not he should do the surgery. Dr. Bauer testified that if Dr. Lillie had not cleared her, he would not have gone forward with the surgery.

In another excerpt, Emily, the ICU nurse and the only person who was in the ICU with Judie on that night, testified that she reported Judie's clinical status to the eICU several times and received treatment orders, which she followed. Her handwritten notes indicated that the systolic blood pressure fell below 50. Steve recalled that 5 days later she told him and his aunt that it never went below 90, and explained that within two hours of that conversation she went into the computer system and changed the records. He indicated that it was not known exactly what she changed, but that she went into the system at least three times and made at least six modifications to the records. At her deposition, she testified that she did not know why or when she modified it.

In another notable deposition excerpt, Dr. Darmstadter, the ICU doctor, who apparently did not know for two days that Judie was in a coma, was asked whether it concerned her that she could not communicate with the patient at all. Her response was a painfully long pause before she said that it did not concern her.

Aurora's materials indicated that the camera in the ICU does not replace a physician at the bedside. The deposition excerpts contained the following: ICU nurse Emily testified that the physician, whether it be the surgeon or the primary care physician, are the ones that make the call as to whether the patient needs an intensive care physician. Dr. Lillie indicated that it is up to a nurse or doctor to make the decision as to who to call and under what circumstances. The anesthesiologist testified that it was his assessment that Judie was being transferred to Emily.

The only physician who had anything to do with Judie's care that night, the one at the airport, testified that she does not know whether there was any physician working in the ICU at the hospital that night, or who was in charge of the patient's care. She maintained that she was not the person providing the care that night, and estimated that she was providing care for 125 to 150 ICU patients that night. The eICU manager for Aurora testified that the average of eICU camera coverage is 160 patients per day.

Emily testified that the cameras are not on all the time. The eICU manager testified that the camera is usually off, and that there are no formal written polices or procedures as to when the camera should be on. Asked whether the patient would benefit from having a doctor present to see and evaluate the patient as opposed to a doctor not present, Dr. Darmstadter said no.

Litigation Tactics

Relative to the anesthesia records, Steve described in the film that the experts all agreed that Judie suffered a massive loss of blood during routine hip surgery, and because of that, the handwritten anesthesia notes made no medical sense. Despite this, having determined that their best chance was to focus on the hospital, the ICU nurse and the eICU camera doctor, Judie's attorney decided to not oppose summary judgment motions by Dr. Bauer and the anesthesiologist, and prior to trial voluntarily discontinued against the primary care doctor and the intensivist, Dr. Darmstadter. These were curious litigation tactics. Even if it was determined that the strongest case involved what happened in the ICU, not pursuing the surgery side of the case and discontinuing against the ICU doctor who was apparently on duty but nowhere to be found, is difficult to understand for several reasons.

First, the mere fact that it was agreed that the anesthesia notes could not be correct renders the anesthesiologist and surgeon highly vulnerable and smacks of a cover-up. Second, everything disclosed in the film up to this point—the spy-cam recordings and deposition excerpts—indicated that the defendants would likely be engaged in a virtual free–for-all blaming each other at trial: the hospital and ICU nurse were poised to say the problem happened during the surgery; the surgeon said it happened in the ICU and was blaming the hospital; the ICU nurse pointed to the surgeon and primary care doctor as responsible for determining the level of physician care in the ICU; the surgeon indicated he relied on the primary care doctor to clear her for surgery; and, the primary care doctor said the decision to operate was the surgeon's. This had all the markings of a remarkable position for a plaintiff to be in at trial, and it was given up by letting the doctors out of the case.

Third, dropping these claims where it was evident that the hospital would blame the surgery and the doctors left the plaintiff vulnerable to the hospital pointing to the surgery at trial and telling the jury that this is where things went wrong. Indeed, it is described in the film that during the trial, the remaining defendants pointed to the blood loss during the surgery and to Judie's preexisting co-morbidities as the problems, while touting their eICU as cutting edge technology. While it was indicated in the film that the trial judge may have prevented efforts to directly blame the doctors, the ability to point to the massive blood loss alone could well provide the hospital a way out.

The End

The evidence exhibited in this film demonstrated what would appear to be a very powerful case against the hospital based upon what happened in the ICU. While there is most certainly a great deal of other evidence that remained on the cutting room floor, this film presents a compelling story of medical and institutional failures, of the denial of personal and institutional responsibility for such failure, and of the devastating impact on the patient and family members that can result from these failures. Judie and her family had a lot riding on this lawsuit. If you want to find out how it ended, you should watch the film.

Thomas A. Moore is senior partner and Matthew Gaier is a partner of Kramer, Dillof, Livingston & Moore.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Big Law Sidelined as Asian IPOs in New York Are Dominated by Small Cap Listings

The Benefits of E-Filing for Affordable, Effortless and Equal Access to Justice

7 minute read

A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

13 minute read

Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250