New York Election Reform Needs Improvement

In their Government and Election Law column, Jerry H. Goldfeder and Myrna Pérez write: Albany passed two reforms that were a long time coming: “early voting” and a June (rather than September) primary election. Unfortunately, when enacting a June primary, the legislature did not take into account how it would impact other election laws, and created a bizarre and confusing election calendar this year.

February 13, 2019 at 02:45 PM

5 minute read

Jerry H. Goldfeder and Myrna Pérez

Jerry H. Goldfeder and Myrna Pérez

Albany is being applauded for enacting several popular pro-voter reforms, including taking the first step in amending the state constitution to allow voters to register and vote on Election Day without a waiting period, and permitting New Yorkers to vote by mail without restrictions or conditions. These changes require passage by two successive legislatures and a voter referendum. If all goes according to plan, then by 2022 New Yorkers will enjoy convenient voting procedures that many voters across the country already have.

Albany passed two additional reforms that were also a long time coming: “early voting” and a June (rather than September) primary election.

Early voting in New York is way overdue—three dozen other states permit it. In fact, New York was recently embarrassed by that bastion of restrictive voting procedures, North Carolina. In defending itself in federal court for imposing a new round of voting obstacles, North Carolina noted the fact that New York lacked early voting opportunities. Albany finally has rectified this.

With respect to moving primary elections from September to June, this change has been advocated by the New York City Bar Association and others for many years. Primaries right after Labor Day, when school is starting and many voters are celebrating religious holidays, interfere with turnout. It is hoped that a June primary will reverse that trend.

Unfortunately, when enacting a June primary, the legislature did not take into account how it would impact other election laws, and created a bizarre and confusing election calendar this year. Consider the upcoming special election for New York City's Public Advocate, a position that became vacant upon incumbent Letitia James being sworn in as the state's Attorney General.

The special election is on Feb. 26, 2019. This date was chosen pursuant to the New York City Charter that requires a special election to be held 45 days after the Mayor's proclamation of a vacancy. (There are no primaries for special elections.) The winner will serve through Dec. 31, 2019. The Charter also requires that the remainder of the Public Advocate's term—from Jan. 1, 2020 through Dec. 31, 2021—must be filled at the general election this November. Because of the new law, primaries for the general election ballot are now slated for June 25th. And to run in the June primary, a candidate must circulate petitions to appear on the ballot, the first day being February 26th—the very same day of the special election.

Thus, on the day voters go to the polls to elect a new Public Advocate for the remainder of this year, they will be asked to sign petitions for candidates for Public Advocate who will take office on January 1st of next year.

The election calendar may get further complicated if the candidate elected on February 26th happens to be one of the four City Council members running for the post. In this scenario, there will be a vacancy in his council seat—requiring yet another special election to be held sometime at the end of April. And petitions for this special election will be circulated in the beginning of March—during the same period during which petitions are being circulated for the June primary for Public Advocate.

Thus, New Yorkers may be asked to vote in February, April, June and November. Moreover, if no candidate for Public Advocate wins the June primary with at least 40 percent of the vote, there will be a run-off election at the end of July. (There are no run-offs in special elections.) It is entirely unclear why the legislature did not take all of this into consideration when enacting recent election reforms.

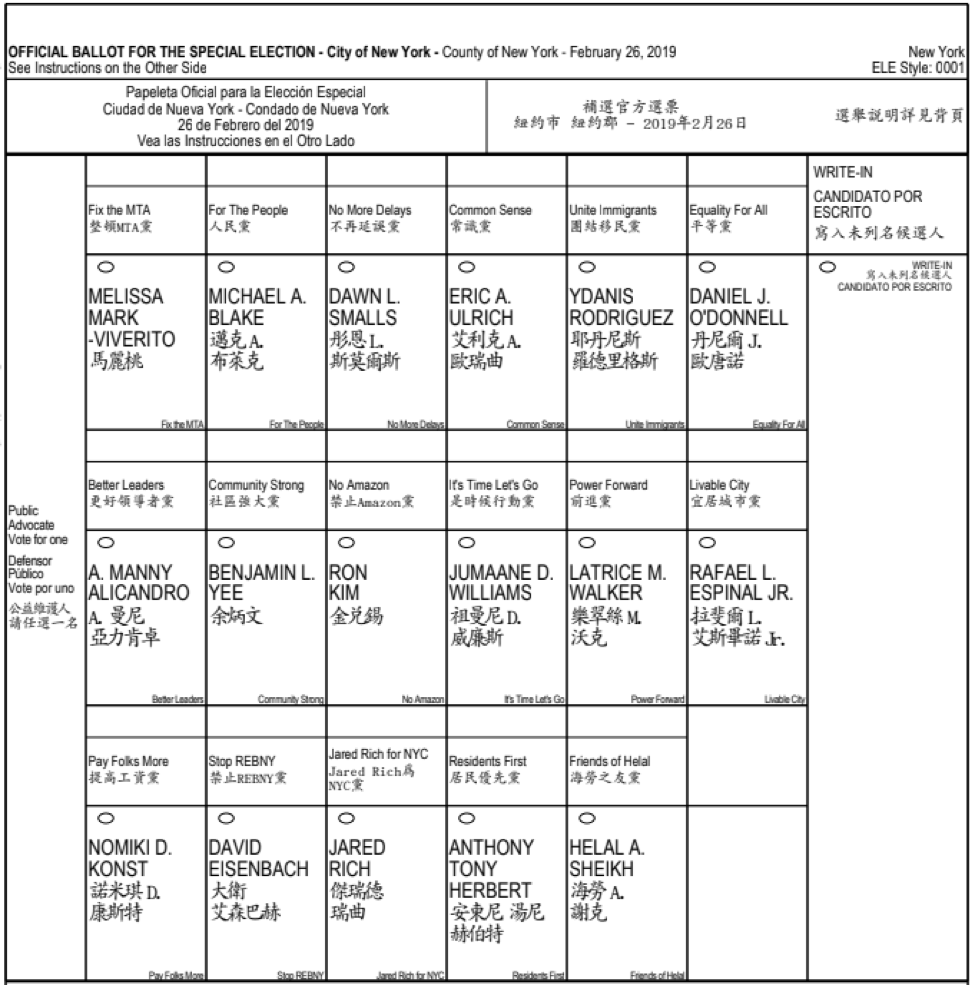

Beyond the irrational election calendar Albany has imposed, it also did not address the manner by which vacancies are filled and the way New York conducts special elections—a topic that the New York City Charter Revision Commission has been asked to address. In the meantime, however, voters are stuck with multiple elections this year, and, to make matters more confusing, no candidate in a special election may use his or her actual political affiliation. Instead, fabricated party names appear above the names of the candidates. Thus, the ballot itself is confusing. Take a look at this sample ballot provided by the NYC Board of Elections:

This sample ballot was provided by the NYC Board of Elections.

This sample ballot was provided by the NYC Board of Elections.A voter who does not know in advance for whom to vote may, therefore, be hard pressed to make any sense of the ballot.

It is laudable that New York took a step forward, but there is obviously more to do. In an era when the public is so attentive to voting restrictions in states across the country, it behooves the bar to focus on reforming our own state's election law to make it easier for candidates to run and New Yorkers to vote. At the very least, Albany should pass automatic voter registration, public financing, better ballot design, and voting rights restoration for community members with past convictions—and the legislature should keep in mind related provisions of election laws so that the result is a coherent, rational process for voters.

Jerry H. Goldfeder, special counsel at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan, teaches election law at Fordham Law School and the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and is the author of Goldfeder's Modern Election Law (NY Legal Pub. Corp., 5th Ed., 2018). Myrna Pérez is the Director of the Voting Rights and Elections Project at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, and regularly litigates voting rights cases.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

So Who Won? Congestion Pricing Ruling Leaves Both Sides Claiming Victory, Attorneys Seeking Clarification

4 minute read

Hochul Vetoes 'Grieving Families' Bill, Faulting a Lack of Changes to Suit Her Concerns

Court System Names New Administrative Judges for New York City Courts in Leadership Shakeup

3 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1American Airlines Legal Chief Departs for Warner Bros. Discovery

- 2New Montgomery Bar President Aims to Boost Lawyer Referral Service

- 3Deadline Extended for Southeastern Legal Awards

- 4Church of Scientology Set to Depose Phila. Attorney in Sexual Abuse Case

- 5An AG Just Specified How AI Could Get You in Hot Water

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250