Why Arbitration Finance Will Become More Popular in 2019

What is certain, even against a backdrop of change, is the permanence and expected growth of arbitration finance. The tool continues to leave favorable impressions on those who interact with it.

March 08, 2019 at 02:30 PM

7 minute read

The arbitration finance landscape continues to shift. Research reveals growing awareness and understanding of the tool, along with increasingly positive attitudes towards it. This comes as a result of continued geographic expansion of its use, most recently as Hong Kong launched its Code of Practice for Third Party Funding of Arbitration, which opened it to arbitration finance. It is also growing despite ICSID's proposed Rule 21: Although this proposed rule could create thorny issues surrounding disclosure of arbitration finance under its facilities, its structuring suggests that any concerns are misplaced.

The arbitration finance landscape continues to shift. Research reveals growing awareness and understanding of the tool, along with increasingly positive attitudes towards it. This comes as a result of continued geographic expansion of its use, most recently as Hong Kong launched its Code of Practice for Third Party Funding of Arbitration, which opened it to arbitration finance. It is also growing despite ICSID's proposed Rule 21: Although this proposed rule could create thorny issues surrounding disclosure of arbitration finance under its facilities, its structuring suggests that any concerns are misplaced.

What is certain, even against a backdrop of change, is the permanence and expected growth of arbitration finance. The tool continues to leave favorable impressions on those who interact with it. And a growing number of users will be exposed to the tool and its applications in the year to come. Moreover, it is all but certain that legal finance will become more popular (and more widely used) in 2019.

The more users encounter arbitration finance, the more favorably they perceive it. In 2019, arbitration finance will continue to become “a common practice” in investor-state and international commercial arbitrations. The reason is simple: “The more users encounter third-party funding in practice, the more favorably they tend to perceive it.” And in the year ahead, it is unmistakable that more users will be encountering arbitration finance in practice.

Let us take two examples. As of February 2019, in Hong Kong, the much-anticipated Code of Practice for Third Party Funding of Arbitration has been implemented by the Hong Kong Department of Justice. That legislation ensures that Hong Kong will be in line with other leading international arbitration centers—such as Singapore—that have already recognized arbitration finance. And in July 2019, the ICC will supplement the data on the composition of ICC tribunals available on its website to include details about the sector of industry involved and the identity of counsel representing the parties. In so doing, the number of claimants in ICC arbitrations to encounter and consider arbitration finance will undoubtedly increase owing to the increased transparency.

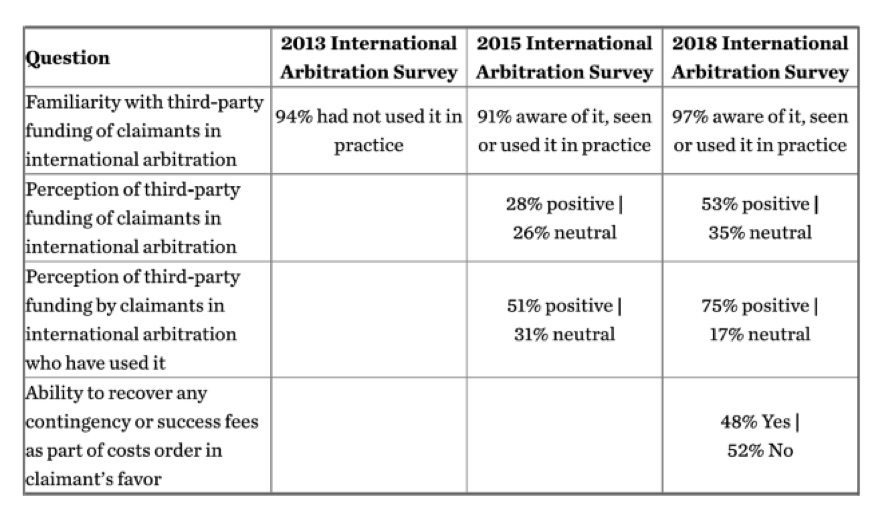

What is more, empirical data from arbitration users support these developments. The latest Queen Mary/White & Case International Arbitration Survey confirmed the steady and significant increase, not only of awareness, but also of positive perceptions of third-party funding. In that survey, the majority of respondents (97 percent) said they were aware of outside funding in international arbitration and had a positive perception of it, particularly those who had actually used it (75 percent). What is more, when compared to previous empirical surveys, in just a three-year span between 2015 and 2018, the perception of third-party funding has unmistakably shifted from neutral to positive among international arbitration users.

ICSID's proposed Rule 21 on the disclosure of arbitration finance and possible implications. ICSID, responsible for administering over 70 percent of all investment disputes, is now working on the fourth update to its procedural rules, a package of amendments scheduled to be submitted in 2019 or 2020 to the ICSID Administrative Council. To that end, on Aug. 3, 2018, ICSID released the Working Paper on Proposals for amendment of the ICSID rules, which includes a rule (Rule 21) on the disclosure of third-party funding.

Practice suggests that an express rule on the disclosure of arbitration finance is unnecessary. The ICSID rules currently do not contain provisions that address arbitration funding, and ICSID cases have been funded for the past 10 years. ICSID itself has confirmed as much, noting in its Working Paper that “in at least 20 recent cases in which the existence of legal finance was at issue before an ICSID Tribunal, the parties disclosed the existence of legal finance and the identity of the funder without requiring an express order to this effect from the Tribunal.” What is more, the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, selected by claimants in the majority of investment disputes not administered by ICSID (but by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the main) contain no such rule. The reason for this is straightforward: Neither a funder nor a claimant in an ICSID or UNCITRAL arbitration has any desire to risk an undisclosed conflict of interest delaying proceedings or jeopardizing enforcement of an award.

While unnecessary, if mandatory disclosure (of the fact of funding and the identity of the funder) is to be required, ICSID's proposed Rule 21 may strike the appropriate balance—but only if interpreted properly. Rule 21(2) requires that a party must disclose funding in a notice to “be sent to the Secretariat immediately upon registration of the Request for arbitration, or upon concluding a third-party funding arrangement after registration.” This stands in contrast to the rules on disclosure of legal finance adopted by other arbitral institutions and in treaty practice, which require the disclosure be made directly to the other disputing party (as contemplated in Article 27 of the CIETAC Investment Arbitration Rules; CETA Article 8.26(1); EU-Vietnam FTA, Chap. 8(II), Sec. 3, Art. 11(1); and EU-Singapore IPA, Art. 3.8).

Against this background, and given the fact that ICSID canvassed these rules and treaty provisions in its Working Paper, the language of proposed Rule 21(1) appears deliberate. And so must be the exclusion of any language requiring disclosure of arbitration finance directly to respondents. This way, the disclosure can be considered by ICSID and the arbitrators once the tribunal is constituted, which will serve the stated purpose of avoiding conflicts but avoid the associated procedural maneuvering once the disclosure is made to the respondent.

An increased focus on arbitration award monetizations. The ability to finance the pursuit of unpaid arbitration awards is perceived as the most significant benefit of arbitration finance to companies (a 118 percent increase over 2017), according to Burford's 2018 Litigation Finance Survey. This is unsurprising, given that when a claimant wins an arbitration award, that claimant may seek to monetize the value of the entire award or a portion of that award. Monetization allows a claimant to enjoy the financial benefit of the award early without the risk of set aside or annulment (usually lasting between 18-24 months) and enforcement proceedings across multiple jurisdictions (often lasting years). And with several of the largest arbitration awards recently rendered pending in set aside or enforcement proceedings through 2019 in courts in the US, UK, Sweden and The Hague, monetizations will likely continue to present an attractive option for claimants with “arbitration fatigue” to unlock the value of those awards.

Regardless of how users of arbitration finance encounter or apply the tool, the research is definitive: As exposure increases, so too will positive sentiment, both of which will lead to increased usage. Expect that in 2019, the growth of arbitration finance will continue unabated, with users around the world (some new, some returning) experiencing its benefits.

Jeffery Commission is a director of Burford's underwriting and investment arm. He practiced litigation and arbitration with Shearman & Sterling and Linklaters before joining the International Arbitration Group at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. He is co-author of “Procedural Issues in International Investment Arbitration” (Oxford University Press, 2018).

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

9 minute read

Tortious Interference With a Contract; Retaliatory Eviction Defense; Illegal Lockout: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Charlie Javice Fraud Trial Delayed as Judge Denies Motion to Sever

- 2Holland & Knight Hires Former Davis Wright Tremaine Managing Partner in Seattle

- 3With DEI Rollbacks, Employment Attorneys See Potential for Targeting Corporate Commitment to Equality

- 4Trump Signs Executive Order Creating Strategic Digital Asset Reserve

- 5St. Jude Labs Sued for $14.3M for Allegedly Falling Short of Purchase Expectations

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250