Immigrants Avoiding State Courts, Legal Services Due to ICE Presence, Report Says

The report, released by a coalition of public defenders, civil legal services providers and others, called on the Office of Court Administration to immediately promulgate a rule requiring those officers to obtain a federal judicial arrest warrant before entering state courts to make an arrest.

April 10, 2019 at 01:30 PM

7 minute read

The presence in and around New York state courts of officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has increased dramatically in the last two years. (Photo: Charles Reed/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement via AP)

The presence in and around New York state courts of officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has increased dramatically in the last two years. (Photo: Charles Reed/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement via AP)

The increased presence of federal immigration officers in and around New York state courts has led to a sharp decline in equal access to litigation and the use of legal services by undocumented immigrants, a new report released Wednesday found.

The report, released by a coalition of public defenders, civil legal services providers and others, called on the Office of Court Administration to immediately promulgate a rule requiring those officers to obtain a federal judicial arrest warrant before entering state courts to make an arrest.

“When people cannot access the judiciary, when they cannot pursue or defend their rights, when they must choose to stay home rather than seek access to justice, then a crucial branch of our functioning society is in peril and it is up to all of us to protect it,” said Terry Lawson, director of the family and immigration unit at Bronx Legal Services. “We must safeguard our courts.”

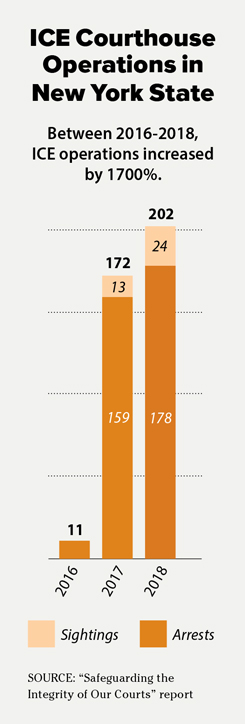

A different report from the Immigrant Defense Project earlier this year found the presence in and around New York state courts of officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement increased as much as 1700 percent last year compared to 2016.

That's led to immigrants choosing to use the state court system and legal services less in recent years, according to the report released by the ICE Out of Courts Coalition on Wednesday.

There was, for example, a 67-percent decline in calls last year compared to 2016 to the Brooklyn District Attorney's Immigrant Affairs Unit hotline, which allows noncitizens to report crimes and request resources without having to worry about endangering their immigration status. There were more than 400 such calls in 2016, but fewer than 150 last year.

Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez attributed the drop to fear among immigrants of making those calls, which he said endangers public safety.

“These actions jeopardize public safety by instilling fear in immigrant communities, which makes victims and witnesses afraid to come forward to report crimes, and unable to get justice,” Gonzalez said.

The higher frequency of ICE officers in and around state courts has also led undocumented immigrants to forego options that could benefit them when faced with litigation or criminal charges, the report said.

The Manhattan District Attorney's Office, for example, reported a major drop in the number of people participating in so-called “clean slate” events last year compared to 2015. Those events allow individuals to resolve their summons warrants on site at a church or community center without risk of arrest.

One such event held in 2015 drew 700 people, according to the report. A similar event held last April was attended by only 200 individuals. The office attributed the decline “in part due to the fear that ICE will show up and round people up,” according to the report.

More than half of the attorneys with New York County Defender Services, meanwhile, said they had clients that took less favorable pleas to avoid having to return to court and possibly being detained by ICE officers, according to the report. A statewide survey also found that three out of every four legal service providers in New York worked without clients who expressed fear of going into court due to the presence of federal immigration officers, the report said.

Those results, along with several other statistics included in the report, should be enough to convince either state lawmakers or top judiciary officials to act on curbing the presence of ICE at state courts, advocates and attorneys argued.

“Judges, public defenders, district attorneys, anti-violence advocates, elected officials, and others have all repeatedly called on ICE to stop courthouse arrests,” said Mizue Aizeki, acting executive director of the Immigrant Defense Project. “Yet ICE continues to refuse, instead escalating courthouse arrests and spreading its disruptive and harmful tactics throughout New York State.”

There are two avenues officials in New York could take to limit federal immigration activities and the possibility of arrests at state courts. The first involves action by the state Legislature, which is already considering a bill to prevent federal immigration arrests in those buildings.

The Protect Our Courts Act would require that ICE officers obtain a judicial arrest warrant from a federal judge before attempting to arrest an undocumented immigrant either inside or on the way to a state courthouse. The bill, sponsored by state Sen. Brad Hoylman, D-Manhattan, and Assemblywoman Michaelle Solages, D-Nassau, would require that counsel for the court system review the warrant before an arrest is made.

“This new report from the ICE Out of Courts Coalition provides disturbing new evidence that ICE's vicious pursuit of undocumented New Yorkers is intimidating witnesses and driving survivors of abuse into the shadows,” Hoylman said. “New York must pass my Protect Our Courts Act to ensure that all residents of our state—regardless of their immigration status—can participate in our justice system and hold perpetrators accountable.”

The other avenue, also recommended by the report, would have Chief Judge Janet DiFiore and Chief Administrative Judge Lawrence Marks promulgate a rule similar to the Protect Our Courts Act. The rule would require that ICE officers present a judicial arrest warrant when entering a state courthouse to make an arrest.

Marks told lawmakers in January that OCA was considering such a rule, but court officials have not announced any action as of yet. Some have also suggested that OCA bar ICE officers from entering state courthouses altogether, but Marks said in January that an order like that could be seen as unconstitutional since the buildings are open to the public.

The report also recommended that OCA block state court employees from assisting federal immigration activities, providing information to ICE officers, and inquiring into the immigration status of an individual in court unless necessary for program service or benefit. That's after a report from Documented, an immigration news website, obtained documents showing some state court officers alerted ICE officers about immigrants in court.

Either option to reduce the activities of ICE at state courts is just as likely as the other. The Protect Our Courts Act was reintroduced in January after failing to pass last year, but it hasn't moved since then. A spokesman for OCA said they were reviewing the report and its recommendations.

“We had requested more information regarding the potential impact that ICE was having on court operations and appreciate the comprehensive work reflected in this report,” said Lucian Chalfen, spokesman for OCA. “We are giving their recommendations careful and serious consideration as we analyze the data.”

The New York City Bar Association also released a statement on the report, calling its findings “disturbing” and asking OCA to take action to reduce the presence of ICE going forward.

“The resulting picture is a disturbing one, with the increased operations of ICE in state courthouses having a clear negative impact on courthouse processes and the administration of justice, with devastating repercussions for some of New York's most vulnerable residents,” the City Bar said in the statement.

A spokesman for ICE said the agency has a policy in place for making arrests at courthouses, and that officers typically only do so if they've exhausted all other options to detain an immigrant.

“U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has a courthouse policy in place, and plans on adhering to its guidance in accordance with U.S. law and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) policy,” the spokesman said.

READ MORE:

Lawmakers Eye Further Steps to Benefit Immigrants as NY 'Dream Act' Approved

NY State Hires 19 Immigration Attorneys to Provide Legal Services Across Regions

Cuomo, Lawmakers Preserve Funds for Legal Services Program for Immigrants in State Budget

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Private Equity Giant KKR Refiles SDNY Countersuit in DOJ Premerger Filing Row

3 minute read

Skadden and Steptoe, Defending Amex GBT, Blasts Biden DOJ's Antitrust Lawsuit Over Merger Proposal

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

- 2California Court Denies Apple's Motion to Strike Allegations in Gender Bias Class Action

- 3US DOJ Threatens to Prosecute Local Officials Who Don't Aid Immigration Enforcement

- 4Kirkland Is Entering a New Market. Will Its Rates Get a Warm Welcome?

- 5African Law Firm Investigated Over ‘AI-Generated’ Case References

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250