A Newspaper Lawyer's Press Pass Through History

The president's fake news-enemy-of-the-people rhetoric, a well-worn tool of authoritarian leaders, has clearly polluted American democracy. At the very least, it has shoved Americans deeper into their tribal corners.

April 15, 2019 at 11:32 AM

6 minute read

Truth in Our Times: Inside the Fight for Press Freedom in the Age of Alternative Facts

Truth in Our Times: Inside the Fight for Press Freedom in the Age of Alternative Facts

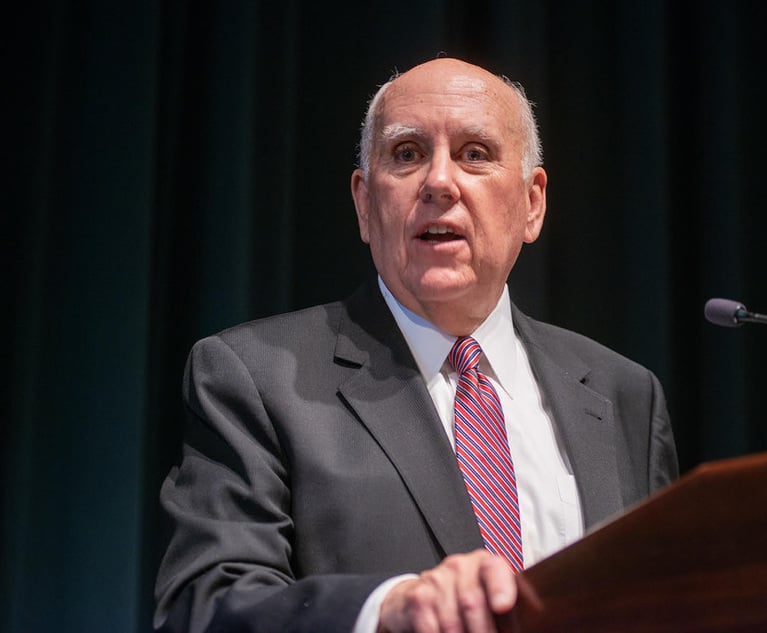

By David E. McCraw

All Points Books

294 pages

President Donald J. Trump's strafing of the press has, in some ways, reinvigorated it.

Cable news networks are flush. Books chronicling chaos inside the Trump administration have become best-sellers. The New York Times and The Washington Post are adding record numbers of subscribers and collecting journalism prizes like seashells.

But to be overly sanguine about the future of the press would be naïve. The president's fake news-enemy-of-the-people rhetoric, a well-worn tool of authoritarian leaders, has clearly polluted American democracy. At the very least, it has shoved Americans deeper into their tribal corners. Recent polling data from Morning Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that the credibility of nine major media outlets among U.S. adults had dropped 5% in the last three years, a decline driven mostly by Republicans.

What will President Trump's lasting legacy on the press and press freedoms be? How concerned should we be?

In the fog of Twitter warfare, it's hard to tell. But few people are better positioned to address those questions than David E. McCraw. As deputy general counsel of The New York Times since 2001, McCraw been a leader in the fight for press freedoms.

In his briskly paced professional memoir, “Truth in Our Times,” McCraw guides us to the front lines of those battles, bringing much-needed perspective to the dangers emanating from the current occupant of the White House. Through stories involving the toughest calls in journalism, he gives us an entertaining civics lesson in the First Amendment, deepening our understanding of how press freedoms have enriched our democracy. Crucially, he provides the context from which those freedoms sprang and suggests darker days ahead if we're not careful.

McCraw's name will be familiar to those in the media bar. He has lectured around the world on press freedoms and in recent years filed more Freedom of Information Act lawsuits than any other media lawyer in the country.

But McCraw gained wider fame during the 2016 presidential campaign following the publication of a letter he wrote to candidate Trump's lawyer, Marc Kasowitz. After Kasowitz had publicly threatened a libel lawsuit over a story about two women who said they were touched inappropriately by Trump, McCraw crafted the newspaper's response.

The letter, just 17 sentences long, lit up the internet. No doubt, the letter's popularity sprung from an antipathy toward Trump and a desire to see him get his comeuppance.

But the rabid response also sprung from an admiration for craftsmanship and press freedom, a deeply held American value. Many swelled with pride when McCraw deftly explained why the article in question had not “the slightest effect on the reputation that Mr. Trump, through his own words and actions, has already created for himself.” Also appealing: the cowboy confidence of the letter, expertly showcased with this killer closing:

“We did what the law allows: We published newsworthy information about a subject of deep public concern. If Mr. Trump disagrees, if he believes that American citizens had no right to hear what these women had to say and that the law of this country forces us and those who would dare to criticize him to stand silent or be punished, we welcome the opportunity to have a court set him straight.”

The lawsuit from team Trump never arrived but McCraw's 10 minutes of fame did, as did a peg for a book. Lucky for us. The letter to Kasowitz is much like McCraw's writing throughout his book: crisp, clear with just the right amount of zing.

Once a journalist, he's also a good storyteller. We are treated with tales of working around the clock to spring reporters held hostage in foreign countries; internal deliberations about whether to publish secret information; and supplications from outside attorneys wanting a shot to represent newspaper in court.

It is enough to give just about any lawyer job envy. His work clearly matters, and his colleagues respect him.

Among the most compelling parts of the book are his discussions with reporters about blockbuster stories. Unlike the cliched lawyer seen in movies who is always fretting about liability, McCraw is a wise friend in whom reporters place their trust.

Not that he puffs himself up. Part of McCraw's charm on the page is a Midwestern understatement and humility. He admits, for instance, that he did not fear a Trump presidency as much as other press freedom advocates did. When friends and colleagues were strategizing about how to prepare for expected combat with the Trump administration, McCraw wanted to wait and see.

“I held out the possibility that some balance would be restored, that the skirmishes between Trump and the press would ebb and flow but ultimately reach some sort of equilibrium, more Nixon than Obama, but within the range of acceptable,” he wrote.

McCraw's hope may have been influenced by the sturdy legal scaffolding that for decades has protected media outlets from the well-heeled and powerful seeking to silence their press critics through intimidation. Armed with the 1964 New York Times Co. v. Sullivan decision and other precedents, McCraw has seen his share of litigation threats from public figures disappear into black holes.

But in the alternative fact Trump presidency, the courtroom may not be where the most important game is being played. McCraw writes that he has learned the limits of the law, a powerful conclusion that merits our attention.

“The law can do only so much,” he writes. “It can give the press the freedom to matter but it can't make the press matter.”

And what if a free press, battered by constant claims of fake news, stops mattering to Americans? McCraw warns that a disregard for a free press can quite easily become a disregard for press freedom.

It's a warning worth heeding.

Andrew Longstreth is a former legal journalist and head writer at the international communications firm Infinite Global. He is based in New York.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

For Safer Traffic Stops, Replace Paper Documents With ‘Contactless’ Tech

4 minute read

Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley: American Painters in London

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Judicial Ethics Opinion 24-89

- 2It's Time To Limit Non-Competes

- 3Jimmy Carter’s 1974 Law Day Speech: A Call for Lawyers to Do the Public Good

- 4Second Circuit Upholds $5M Judgment Against Trump in E. Jean Carroll Case

- 5Clifford Chance Hikes Partner Pay as UK Firms Fight to Stay Competitive on Compensation

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250